By Alexa Linton, Equine Sports Therapist

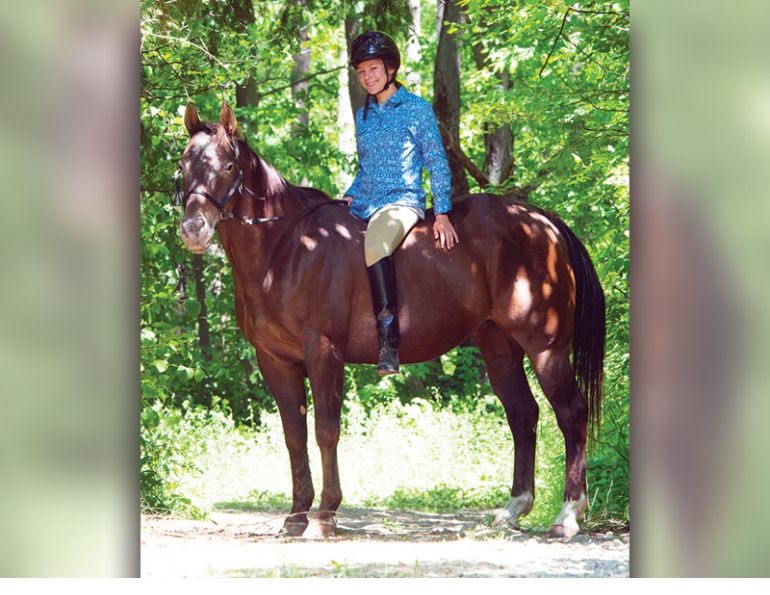

Recently, I officially retired my mare Diva from riding at age 25. She had started showing signs that riding was no longer a comfortable or enjoyable experience. I noticed her topline dropping and her hind end becoming stiffer (which was confirmed as the early stages of hock arthritis in her left hind). In general, Diva’s body was no longer receiving a benefit from being ridden. I decided I am not comfortable medicating my horse so that I can ride her. To ride is a privilege and not a right. If a horse requires medication to be “comfortable” while ridden, but is sound and comfortable when unridden, why should she be ridden?

I believe that riding should be “for the horse.” The intention should be to benefit the horse by developing their body toward greater health and strength, focusing on longevity of their tissues in addition to the mutual enjoyment of both horse and rider. Supportive practices around riding should ensure that the horse’s joints, ligaments, and tendons are cared for by the type of training being done, and that the horse generally feels at ease, connected, and happy under saddle. If riding our horses is our priority, it is important to assess our motivations, desires, and conscious and unconscious agreements around this.

Related: Equine Boarding School

Studies examining overall health show that most horses reach skeletal maturity between five and eight years old, depending on factors like the individual horse, breed, nutrition, and movement. Photo: Rita Kochmarjova

Are we willing to take a horse-centred approach to starting and riding our horses, allowing for the unique timeline of each horse, considering the maturity of their body and mind when making decisions, and prioritizing the horse’s needs during their transition to being ridden (or, in Diva’s case, to being retired)? If you are unable or unwilling to put your horse’s needs for longevity, maturation, and health ahead of your own need to ride, examine the reasons behind your decisions and how your choices might impact your horse and your relationship with them.

On that note, let’s look more closely at the question: Is your horse ready to be ridden? I am firmly in the “wait a good while until you ride them” camp, which probably won’t come as a surprise! As an equine bodyworker I have seen many prematurely retired horses with career-ending and preventable arthritis, kissing spine, and joint or tendon injuries. Knowing what I know now, I would wait to back a youngster until they are five or six years old. If I was buying a young horse, I would steer clear of any horse started under saddle, even gently, before four years of age, to reduce the chances of them developing joint issues, kissing spine, or other debilitating issues. I have read the research on bony development and have put my hands on hundreds of horses all telling me the same thing — in this industry, the norm is to start horses too young, and before they are ready physically and mentally. Given what I know about the impact of the environment, I would also look for a young horse that had been given the “three Fs” — friends, forage, and freedom — to allow their body to mature in the most species-specific way possible. Though it is still very common practice. I will share some of the research on why starting youngsters under saddle too early is not a good idea, and how you can support your horse to have a long and healthy life all while having a good riding career.

We humans are inherently impatient and waiting for a horse to grow up can be both challenging and expensive. Even so, is it as challenging and expensive as having to retire your horse early, medicate, or face a more permanent choice because of joint or tendon issues, kissing spine, or dangerous behaviour rooted in pain? Sometimes it comes down to money and not thinking long-term. Most horses stay in a home less than four years on average; hence, many horse trainers and owners will never have to reap the issues they sow by starting a horse under saddle before they are ready.

Groundwork can help prepare a young horse for life’s work, and one of my favorites is a long walk in nature in-hand or by ponying from another horse, incorporating some hills if possible. Photo: Clix Photography

In the research I found on skeletal maturity, the results were varied. I believe this is likely because parts of the horse industry benefit financially from starting and riding very young horses and recognizing potential concerns could be challenging to address. There are several research papers stating that exercise is important for young horses to develop bone density, citing a lower percentage of limb lameness in the short term of the studies, compared to control groups given no exercise and no turnout. Not included are statistics on kissing spine, which show over 30 percent of ridden horses affected, and long-term outcomes such as arthritis. I definitely agree that exercise is helpful for young horses. There are many great ways for young horses to develop joint and tendon strength, good bone density, balance, connection, and capacity that do not place horizontal forces on the developing spine, or detrimental vertical loading on a developing pelvis or limbs. Countless groundwork practices do just this, as well as species-specific horse-keeping practices that ensure young horses develop strong bones and tendons to meet the demands for riding and more — when they are ready. Access to the “three Fs” goes a long way toward ensuring your young horse will be a strong and healthy partner for many years to come.

Related: Get Your Horse On a Track System

In studies that look at the full health picture, the consensus is that skeletal maturity in most horses occurs between five and eight years old, depending on the individual horse, the breed, and environmental factors like nutrition and movement. The research is mainly looking at the ossification and closure of growth plates, the transition of soft susceptible cartilage into strong sturdy bone. Dr. Deb Bennett PhD, in her articles About Maturity and Growth Plates and Timing and Rate of Skeletal Maturation in Horses shares that while many growth plates fuse prior to three years of age in most horses, certain joints are particularly late-forming. These include the growth plates on the tibial and fibular tarsals in the hock joint, which do not fuse until over four years of age, making the hocks a weak point and susceptible to injury in young horses; as well as the pelvis, which does not fully fuse until well over four years of age and often much later. Dr. Bennett’s research shows that the ossification process by majority works from the bottom up, completing with the spine. In fact, the spinal column is not complete in its formation until at least five-and-a-half years of age, with the vertebrae at the base of the neck fusing last (upwards of six years at times). In taller horses, the age of skeletal maturity increases, and geldings will take approximately six months longer than mares. Dr. Bennett also shares that because of the horizontal direction of joint loading on the spine, specifically with riding, it is easier to cause an injury to the spinal column in a young horse as well as harmful compensation patterns, something that can have lasting and painful outcomes.

In her episode on the Emotional Horsemanship podcast, equine dissectionist Becks Nairn gives a full account of her findings on dissections of dozens of off-the-track Thoroughbreds, some as young as three years old. She reports multiple bruised and crushed femoral heads and acetabulum as well as splayed pelvises with unfused pubic symphysis and sacroiliac joint instability due to early loading of non-ossified joints. Conversely, horse owners who have chosen to wait to ride their horses until they are more than five years old reported positive results, with happy, balanced, willing horses, and great partnerships.

Related: Safe and Sensible Equine Herd Integration

How can we know when our horses are ready for ridden work and how can we prepare them well? Let’s get into it!

In recent years I’ve come to more fully understand the value of groundwork for building a solid physical, mental, and emotional foundation, and a connection that carries over to under-saddle work. It took a while to make the shift, as riding can be a primary part of our relationship with horses, but now I love groundwork as much as riding, and maybe more. There are many groundwork practices that can be started early to build bone, joint, and tendon strength, as well as mental and emotional capacity and resilience.

On the ground there are countless things to work on to prepare a young horse for whatever their life holds. One of my favourite practices is going for a lovely long walk together in nature, finding some hills (great for everyone’s fitness), and incorporating some classical dressage exercises to build focus and body awareness. Some of my recommended teachers, practices, and methods for groundwork are Elsa Sinclair (Freedom-based Training), Lockie Phillips (Emotional Horsemanship), Josh Nichol (Relational Horsemanship), Shannon Beahen (Humminghorse), Kathy Sierra (Pantherflow), Hannah Weston (Connection Training), as well as Academic Art of Riding, and Legerete. I have learned that you can work with almost all the concepts on the ground that you like to work with under saddle, but without the same risk to tissues and the need to push for something your horse is not ready for.

Many horses do not have the strength in their back to carry a rider at two or three years of age, and any pain and discomfort they experience around saddling and riding can manifest as stress behaviours such as objecting to the saddle and girth. Photo: Clix Photography

While we’re on the topic of preparatory groundwork, let’s talk about the thoracic sling and its role in readiness for ridden work. This was a pivotal understanding for me, particularly with my mare Raven, and I believe for many horses it is essential to understand and evaluate. Many horses do not naturally develop their thoracic sling (the muscular sling holding up the horse’s shoulder girdle) in a way that is conducive to carrying a rider, and they require assistance to develop it. Contrary to popular belief, the natural carriage of many horses is not that of a “ridden” horse. In some horses, like Raven, nerve impingement at the brachial plexus occurs as a result of thoracic sling issues, potentially resulting in problems with girthing and saddling, behavioral issues due to pain, as well as weakness and susceptibility to injury. Thoracic sling activation is work that should be prioritized prior to ever getting on your horse to ensure a healthy back and hind end function, and can be started at two or three years old to prep them in a good way for under-saddle work. It is important to understand that many horses do not have the strength in their back to “meet” their rider, with their thoracic sling and back collapsing under the rider’s weight. This can make a horse prone to everything from hock arthritis to pelvic instability to kissing spine, as they must constantly compensate for this weakness in other areas. I highly recommend the Balance Through Movement Method™ with Celeste Lazaris as a simple, effective method to support the horse in this way, using three main pillars outlined in an easy-to-follow online format. Also, Kathy Sierra of Pantherflow outlines what she calls “crunches,” which are a way of working with and assessing the strength of the back, and determining whether your horse is able to hold your weight.

Related: When Horses and Riders Hurt Themselves

To help you assess and answer the question of your horse’s readiness to be ridden, it’s important to have a team you trust, including a veterinarian, bodyworker, and trainer. If any of these team members encourage riding before the horse is three years old, it may be time to seek out a new team member. Ideally, your team of equine professionals will offer solid and honest feedback on your horse’s development, including how the horse’s body is feeling, the support needed in training or environment to ensure the transition to riding is smooth and pain-free, and to catch any potential health concerns or red flags.

It is also important to talk about horses that will never be ready to be ridden. There are many horses that will never benefit from being ridden due to multiple factors including pain, developmental disorders, structural malformation, and genetic abnormalities such as equine cervical vertebral malformation, trauma and more. I have met a number of these horses and depending on the factors involved, challenging decisions may have to be made. Thankfully, many can live fulfilling lives as unridden horses, depending on their care. This is just one reason to accept all behaviour as important information about your horse’s physical, mental, and emotional state.

If your horse shows stress behaviour about saddling and riding, they are likely telling you they are experiencing pain or discomfort, are unsure of their balance and coordination (very common for young horses) or feeling overwhelmed/flooded by too much happening too quickly. My rule of thumb is to go slow, then go slower, and then go slower than that. This way we don’t miss important information that our horses share with us and can be confident that they are truly ready (or not) for each step.

Related: How to Support Your Horse Through Change

Although it’s what we are used to seeing when starting horses, stress behaviour displayed as bucking, rearing, bolting, or freezing are not indicative of a horse that feels safe or comfortable with saddling and riding. Rather, this type of behaviour shows there is more preparatory work to be done, and more time and support needed before the horse feels ready to be ridden. If the stress behaviour continues, it’s essential to pause and investigate possible causes with your health team. Training practices that use force and escalating pressure to ensure compliance do not leave space to listen to feedback or get a true reading on the horse’s readiness to be ridden. Ideally, starting a horse under saddle should be boring and uneventful. You are laying the foundation for how your horse feels about riding for the rest of their life, and it’s well worth taking the time to build a strong base physically, mentally, and emotionally.

Your horse’s bodyworker, veterinarian, and trainer can provide valuable feedback and help you assess your horse’s readiness to be ridden. Photo: Clix Photography

Many of us have grown up with the tradition of starting horses at two or three years of age. I truly hope that when we know better, we will do better, and that we can begin shifting the norms in our industry for the betterment of horses. Part of changing the industry is changing our individual choices for our own horses, including choosing to buy later-started horses and rewarding breeders and trainers who wait to start horses under saddle, and who provide their horses with a species-specific environment. Part of change is waiting to start your own horses, praising others for waiting, and getting comfortable incorporating more supportive groundwork that builds confidence, connection, balance, and bone density.

I’d love to see more horses like Diva, retired comfortably and in good health at age 25, enjoying their golden years. That starts with making choices in their younger years that are truly in the horse’s best interest. Horses deserve to live long and healthy lives free of pain, and have enjoyable riding careers, if that’s what works for them.

Related: Is Desensitizating Your Horse Helpful?

Related: A Guide to Clicker Training

Main photo: 24K-Production