Exploring why and how to make the switch from snaffle to leverage bit, and the language of neck reining.

By Lindsay Grice, Equestrian Canada coach and judge

Do you think I should I try a different bit? This question is familiar to me as a coach, launching me and the rider I’m working with into a bigger conversation. My answer will be shaped by the reasons why the rider is considering another bit option.

Simply put, a bit is a tool to communicate a message from a rider’s hand to a horse’s mouth. When a rider hits a training impasse she may wonder: Could more bit get my message across more clearly?

Before transitioning to a curb bit, does your horse understand bend, flex and leg-yield using the snaffle? Photo courtesy of Lindsay Grice

Related: Keep Your Horse Fit During Time Off

Another bit option might involve staying within the snaffle family of bits or transitioning to the curb class of bits.

The difference? Snaffle bits communicate with direct pressure, applied by the rider’s hands through the rein to the bit. The rein is attached to the bit’s mouthpiece, so the horse feels an equal amount of the contact taken by his rider.

A curb bit uses the leverage principle to magnify the rider’s contact. More on basic curb bit function later.

Variations within both classes of bits are endless, with new varieties making their debut even now at a tack store near you. While technicalities of bit mechanics are a topic for another article, you can refine your choice by understanding the general principles of bitting or how the parts of the bit affect the individual structures of your horse’s mouth and head.

Within the general categories of snaffles and curbs, the answer to the question: Should I switch from a non-leverage to a leverage bit? depends on the reason. Answers may include:

- A search for more effective communication. To motivate your horse to respond more promptly to your rein aids; curb bits literally leverage your rein signals.

- As the next step in your horse’s education. Training in a curb bit is like learning to use a new tool; neck reining is learning a second language.

Let’s unpack each of these reasons why you may opt to switch to a new tool, and then some tips on how to transition smoothly. Finally, I’ll share advice for speaking fluently using that tool.

Related: Struggling to Plan Your Horse’s Training Sessions? Here’s How to Improve

Curb Bits in Search of a Lighter Response

Dialing up their horse’s motivation prompts many riders to try the leverage route. The action of a curb bit enables a rider to use more subtle rein aids and lighter contact than a snaffle. Because leverage action magnifies a rider’s hand, it takes less movement to achieve a lighter response. English leverage bits include pelhams, kimberwicks, and double bridles. The range of curb bit options for Western riders is infinite.

Introducing a curb bit’s action from the ground — flexing laterally. Photo courtesy of Lindsay Grice

Is “more bit” the answer to a dull or resistant horse? Amplifying your signal to a horse with a missing link in their understanding is like a local shouting to get their message across to a tourist who doesn’t know their language. Louder isn’t clearer; it’s just scarier. Regardless of the bit, our ultimate goal is to use our inside voice — the lightest of pressures.

Riding effectively can be distilled to a system of signals and responses — pressures and releases. Your hands telegraph signals to your horse, such as slow, turn, or flex, using several rein techniques. I regularly ask the riders I coach to describe what type of rein aid they’re using — direct, opening, or indirect.

As your horse responds correctly, you respond with release. If he offers the wrong answer, you keep the pressure steady or even increase it. It’s like a conversation with your horse. By trial and error, he learns that a certain response yields a consistent release. It’s worth considering that the “dull” or “busy-mouthed” horse has quite likely tried a few options to find relief from the bit pressure, yet none seem to shut it off.

Related: Resolving Bit Resistance in Your Horse

So, before heading to the tack store for a different bit, ask yourself:

- Does my horse completely grasp my system of rein signals?

- Am I delivering my message skillfully?

- Do I understand the mechanics of how this new bit works and on which parts of the horse’s mouth?

If the answer to these questions is yes, only then explore a different choice of bit.

Curb Bits as Next-Level Education

Most breed associations require Western horses to be exhibited single-handed in a curb bit, starting in their sixth year. In novice level classes, riding with two hands and a snaffle bit remains optional.

Using both reins I test the rein-back, softening the contact with her first step back. I’m patient if the horse is initially confused. Photo courtesy of Lindsay Grice

Most Western horses and riders I work with make the transition from snaffle to curb when they’re ready to compete in pattern classes such as horsemanship, ranch riding, or trail patterns, in which they’ll need more “handle” — extra steering finesse for advanced maneuvres.

Leverage Bits 101

The class of leverage bits divides into categories and subcategories, each containing a host of patented variations. All are designed to apply pressure to the following regions of the horse’s mouth and head:

- Lips

- Bars

- Tongue

- Roof/palate

- Chin groove

- Poll

How does a curb bit function? A signal from your hand rotates the lower shank rearward and the upper shank forward, as far as the curb strap will allow. The more the upper shank shifts forward, the more pressure is directed to your horse’s poll.

The amount of leverage employed depends on where the mouthpiece is situated on the bit’s shank. If the ratio of shank below the mouthpiece is greater than above, there’s greater leverage.

The style and alignment of a bit’s shanks will also affect the leverage. The amount of tongue and bar pressure your horse experiences when the shanks rotate will vary with the design of the bit’s mouthpiece. A straighter mouthpiece provides less tongue release than a jointed or ported mouthpiece.

Related: Turning Around: Pirouettes, Cow Turns and Reining Spins

Misinterpreting my neck rein signal, the horse turns toward the rein pressure instead of away from it. Photo courtesy of Lindsay Grice

Snaffle to Curb, Step by Step

I introduce any new bit to a horse from the ground before climbing aboard. By asking my horse to flex his head from one side to the other and take some backward steps, I let him discover the answers to questions I’m asking with an unfamiliar bit action. Once he gets the hang of the new equipment, I follow the same routine from the saddle. I typically introduce the language of leverage with a flexible, double-jointed mouthpiece and short, swivel shanks. Because the oral cavity of each horse varies in size and shape, try a new bit for several days to observe how your horse responds. Admittedly, this can become an expensive process — most horse people I know accrue a fine collection of “experiments” at the bottom of their tack boxes.

The Language of Neck Reining

Mastering the language of neck reining is a high school credit in the education of a Western horse, and a prerequisite for disciplines in which the rider uses their free hand to open a gate, drag a log, or rope a cow. However, many riders confess that teaching their horse to neck rein is a bit of a mystery.

As an English rider, when entering the Western world years ago I felt awkward riding with one hand. Like many, I’d train at home with two hands and hope that the stars would align when I entered the show ring with one hand — a very bad plan. No surprise, to become fluent in a second language you’ve got to practice. French immersion students rise above their French-in-class-only friends by using the language every day, in every class. I advise the riders I coach to use one hand, however awkward they feel, whenever they ride with a curb bit. That’s what I did years ago and now I ride as well with one hand as with two.

With direct reining, your horse figured out that he could release bit pressure delivered to the corner of his mouth by turning towards it. Now he’ll learn to turn away from pressure on the side of his neck.

Related: Continuing the Bridle Horse Tradition

While maintaining neck rein pressure I correct the horse’s counter-bend using the familiar direct rein. Photo courtesy of Lindsay Grice

It takes MANY repetitions for a horse to make the connection — turn my neck away from the rein pressing on my neck and… the rein goes slack. At first, expect a communication gap. He’ll misinterpret that pressure on the side of his neck as an “indirect rein.” Counter-bending, he’ll likely tip his nose toward the pressure.

What to do: Without interrupting that neck rein pressure, follow up with your free hand, using a direct rein correction to steer his head away from the neck rein. As soon as his nose tips into the helper-rein and away from the neck rein, let both reins go slack.

Step 1: Neck pressure.

Step 2: Opposite direct helper-rein.

Step 3: Slack.

If the three steps aren’t used independently, the lesson won’t click. Sooner or later, after methodical repetitions, your horse will connect the dots and Step 2 will be eliminated.

Related: Navigating the Gate with Your Horse

An English leverage bit, the pelham bit can have a solid or a jointed mouthpiece and is used with four reins. It has elements of both a snaffle and a curb bit and can function as either depending on how it is used by a knowledgeable rider. Photo: Dreamstime/Nigel Baker

Slower is Faster

I do a lot of walking …and turning …and walking …and turning —utilizing breaks for neck reining in between other work. Resist shortcutting the process by slipping your index finger down between the reins to tip your horse’s nose into the turn. Alas, like never removing training wheels, these horses never truly learn to neck rein if they’re aided by sneaky direct reining. Like any skill, master it at a walk and jog before stepping up to lope.

A common sight at higher levels of dressage and in certain show classes, the double bridle has two bits and four reins. One bit is a modified snaffle bit called a bradoon, which is smaller in diameter with smaller bit rings than a traditional snaffle and sits above and in front of the other bit, a curb bit called a Weymouth. Photo: Shutterstock/Satria Nangisan

The Role of the Bit Operator

The hands at the other end of the bit play a crucial role in its effectiveness. An honest self-assessment is in order before transitioning to a leverage bit: How clearly can you communicate your signals with the snaffle? As confusing as language lessons taught by a teacher with a heavy accent, so are steering lessons communicated via noisy reins. If your arm is out of sync with the stride of your horse, or if your hand tends to be tense or acts abruptly when you’re distracted, hold off on introducing a leverage bit.

Contact — Snaffle to Curb

Soft contact is the standard set in most equine association rule books. As a judge, I’m required to penalize lack of connection in equitation and some Western classes. For example, AQHA horsemanship rules specify: “Reins are adjusted for light contact with the horse’s mouth. At no time shall reins require more than slight hand movement to control the horse.”

Of course, rein contact varies across riding disciplines. Western riders operating with leverage bits will have more pronounced rein relaxation to allow shanks to return to neutral.

Neutral rein contact is an amount your horse doesn’t recognize as a signal. With a curb bit, it’s when the shanks hang in a neutral, balanced position and the curb strap is slack.

Overly firm contact is relentlessly holding the horse in place or in pace. Horses held with tight reins don’t develop self-carriage. When a horse’s correct response isn’t rewarded with release, he feels trapped with no option to escape the pressure. We owe it to our horses to provide a clear answer to the question: What behaviour will turn off the pressure?

Related: Lunging Horses - Why Bother?

Related: Crossing Poles In Stride for English and Western Riders

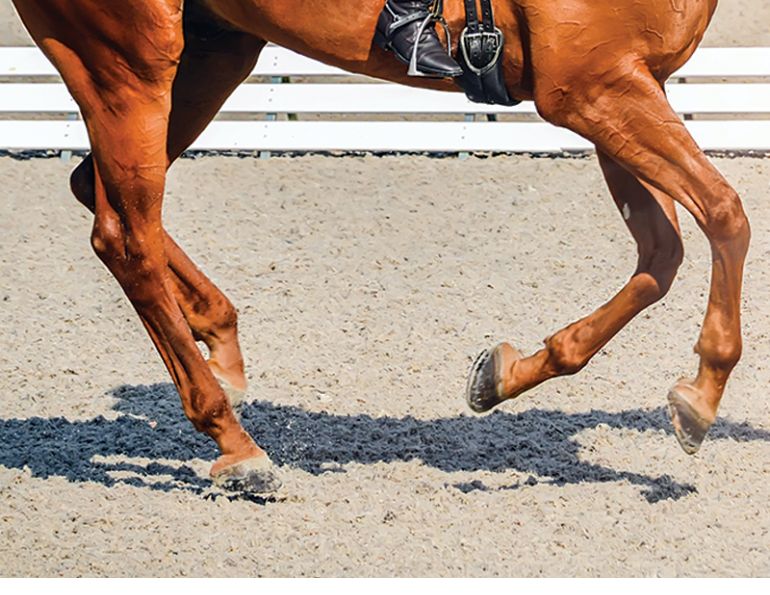

Main photo: The horse correctly bends away from my neck rein, arcing her body around the turn. Photo courtesy of Lindsay Grice