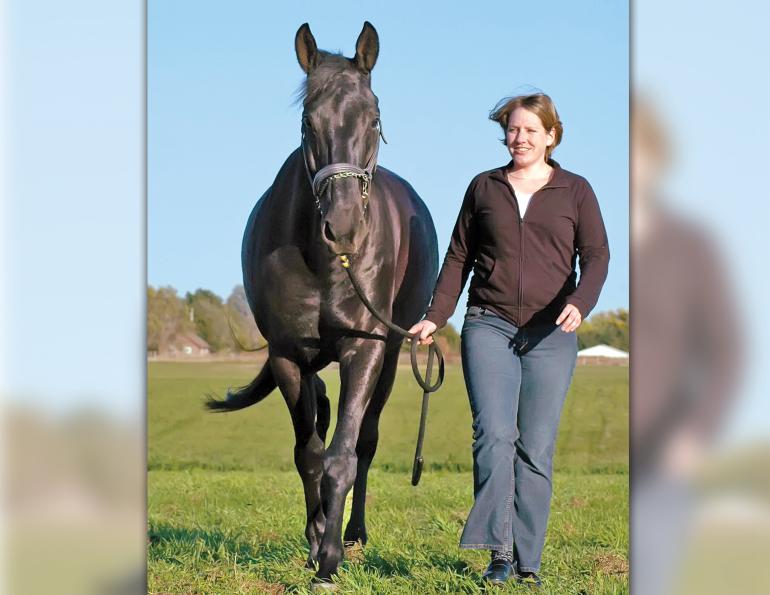

By Lindsay Grice, Equestrian Canada coach and judge

It often feels practical to skip lunging your horse if riding time is limited. Cutting out groundwork fits easily into a culture focused on speed and convenience. For some riders, lunging appears redundant — an awkward task that offers less control than simply climbing on and letting the horse settle under saddle. Others dismiss it as dull or monotonous. At events, a difficult horse on the lunge can be a source of discomfort or even a safety concern in shared spaces. And doesn’t all that circling put strain on the horse’s limbs.

Despite these perceptions, I strongly believe in the value lunging offers to both horse and handler. It’s a technique worth practicing and improving, even if it feels unnatural at first.

Lunging as a Learning Tool for Riders

Many of my lessons in horsemanship have come through careful observation — whether standing by a pasture, watching from the sidelines at a competition, or while mounted. Spending time with horses on the end of a lunge line has sharpened my ability to interpret equine cues. I’ve learned to recognize the meaning behind posture, expression, and movement — signs of worry, focus, or softness. Lunging has given me a clearer understanding of how horses communicate through their bodies.

Surprisingly, many capable riders don’t “read horse” well — they’ve skipped the groundwork necessary to pick up the subtleties of horse language. I’ve noted a key distinction between riding and horsemanship: having a good grasp of ground control. “Horsemen” have well-timed pressure and release. They read a horse’s inclinations and movements and are readable in return.

For me, lunging has tuned my eye through comparing the movement of hundreds of assorted horses, evaluating strengths and weaknesses in their ways of going. Like a teller who handles countless “sound” bills is quick to detect a counterfeit, by studying the profile of a lot of sound horses, even a subtle lameness will be noted by the rider who lunges. Such minor unsoundness may be missed under saddle.

More than a chance to blow off steam, lunging is an extension of your training. In fact, research and experience attest that letting a horse rip around and “get it out of his system” is counterproductive and, because he’s a prey animal, it only winds him up like a top.

Lunging has kept me safe! I won’t climb aboard a horse that’s distracted, resistant to pressure, or way too fresh. In short, I want him to be mentally ready to answer “yes” to my every request by the time I mount up. Otherwise, I’m setting the horse up to ignore my signals like a mother who tries to talk to her teen about his exam study plans at Wonderland. Allowing a horse to ignore your cues is teaching your horse to ignore your cues.

Related: Develop Your Horse's Topline

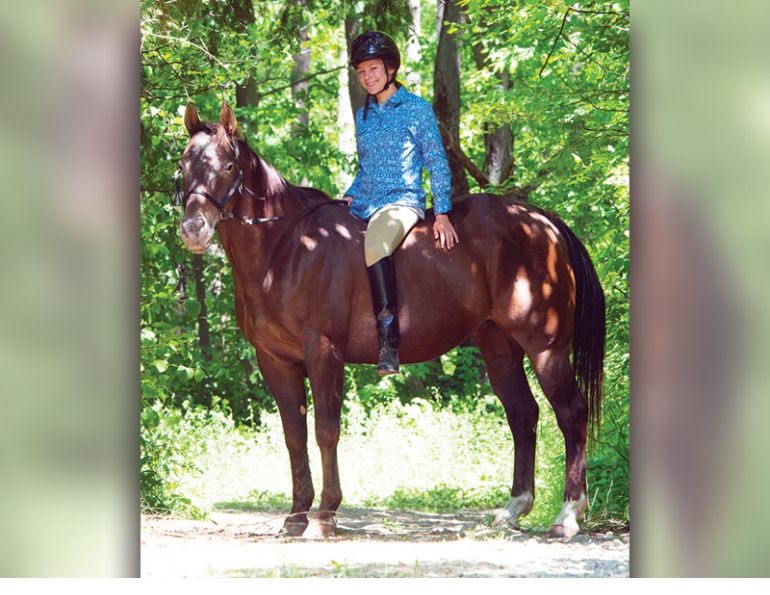

Lunging Benefits for the Horse

Done correctly, lunging teaches a green horse to organize and balance himself at all gaits and in transitions, without the added factor of a rider. The horse learns to slip, not blast, into upward transitions. He discovers that opting for the inside lead takes less effort than the outside lead and that cross-cantering feels really awkward.

The horse learns to keep his attention tethered to the hub of the wheel: the lunger. Through the lunging process, I confirm my role as decision maker. The horse follows my initiative and responds to my body language. The onus is on me to be readable and fair.

Lunging is a useful tool in a new environment to test the horse’s attentiveness before climbing aboard. Even though the horse is experiencing sensory overload in a new situation, lunging helps him remember those skills he’s familiar with, just like we practiced at home.

Reestablishing the building blocks in your training foundation at the start of a session is like a circle check before driving your truck and trailer. Are all systems working well before we take it on the road? These include voice commands and yielding to pressure — the language we use on the ground extends to the conversation under saddle. We speak the same language at home as at a horse show. Skipping training steps inevitably leads to stepping backwards in the process — it’s false economy.

Lunging Basics — Easy as Pie

Think of your positioning like a pie slice — your horse at the base of the triangle and you, in neutral position, at the point (Figure 1). Your lunge line and lunge whip form the two sides of the triangle, with the tip of your whip lowered. Move sideways, slightly behind your horse and elevate your whip arm to send him forward. Slide sideways, toward his shoulder to direct him straight for a few strides, enlarging the circle. This tends to slow the horse as well. If you slide too far in front of his shoulder, however, he may turn around on you.

Photo: iStock/JeanGill

Lunge Line Lapses

Out of control — The horse is oblivious to the person on the other end of the line and whirls around at his pace of choice (typically whinnying). What’s more, the horse cuts in toward the lunger. In a herd, more dominant horses move those less so. The less dominant horse defers his space and peace reigns. This language of pressure and release will make sense to your horse. When you move towards his shoulder and point your whip, make sure he steps away from you, widening the circle. Resist stepping back from the horse to keep your lunge line taut – move him away from you. When you step and gesture your whip toward his hind end, you should expect him to accelerate promptly. Done well, lunging becomes like a dance.

I like a horse to remain perpendicular to me when he stops. Turning in from the rim of the circle, toward me, is contrary to the defer-your-space theme of our ground training. Your horse’s ears should always be tuned in to you, checking in for your measured voice signals and gestures.

Related: Ride with Balance, Flexibility & Strength

More than mindless miles on the odometer — Lunging is more than simply exercise or a way to wear a horse down without thought to any training. Instead, ask your horse lots of questions in your lunging conversation to keep him connected to you. Will you move away from me? Will you lengthen your stride? Will you slow down? Change your location and shift your circle around the perimeter of the ring.

Complex dialogue — Like The Boy Who Cried Wolf, chattering desensitizes your horse to your voice and as a result, he won’t respond when you really mean it. Keep your commands simple. Horses understand tone more than the words themselves. The commands I use are fairly universal — a cluck means move or accelerate; “whoa” signals a complete and immediate stop; kiss is for canter; and a long “aahh” sound (as in waaaaaalk or traahht) signals a downward transition. Any voice commands my horse disregards will be followed up with my whip (for upward transitions) or pressure from my lunge line (for downward transitions).

Use the exact same commands you’ll use under saddle. If saying “trot on” won’t fit your riding program, don’t use it on the ground.

Constant nagging — If lunging becomes an aerobic activity for you as much as for your horse, you’re working too hard. If it dawns on you that if you stop working, your horse stops moving, it’s time to expect your horse to take more responsibility. Self-carriage is when the horse maintains his rhythm, pace, and line by himself without you holding him there. I aim to use my whip thoughtfully — no threatening or stagecoach cracking. If my horse ignores my cluck and whip gesture, I promptly cast the lash toward him to flick him with the tassel — a bit like fly fishing, I guess. Enough to wake him up, but not to flee.

Tug of war — When it’s hard to discern who’s lunging whom, lunging becomes a tug-of-war. The lunge line should always be soft between the horse and the lunger. I insist that the horse find his own balance and not pull on me. Lightness to my hand on the lunge translates to lightness to my rein aids.

Using a rope halter (Figure 2) or lunging cavesson (Figure 3) provides more control and focused pressure if needed. Lunging with a plain halter invites the horse to lug on pressure or even head out of the circle on a tangent. A human is no match for a 1000-pound animal on a beeline for the gate. An experienced lunger builds a rapport through lunging. Her hand communicates a thoughtful and timely “resist and release.” For such a handler, using a chain over the nose (Figure 4) can afford more motivation for fine-tuned communication. The horse feels no pressure as long as he stays within the perimeter of the circle. Training systems vary — some horsemen thread the line through the bit and over the poll, clipping to the opposite side (Figure 5). Because I build toward side reins, connected to the bit, I opt to attach the line elsewhere to avoid conflicting signals.

Photos: Lindsay Grice

Playing — My horses can save their bucking for the paddock. As prey animals, the faster a horse’s legs go, the faster his heart beats and adrenaline pumps. Expressing the flight response makes a hot horse even hotter.

Keep a lid on a fresh horse. I keep to a trot until he’s composed and never let him initiate the canter. In addition to winding a horse up, ripping around on a circle causes strain on his joints.

Fishtailing — The root of cross-cantering and breaking gait is allowing the haunches to drift offline. I keep a horse aligned by lunging in a series of straight lines instead of a true circle. Using side reins helps to keep his train cars on the track. A horse in alignment also has weight distributed evenly on all legs. As I see it, lunging itself isn’t stressful for the horse’s legs, but unbalanced lunging is. An added bonus for the lunger — walking on your own octagon shape helps thwart the dizziness of spinning on your heel.

Focused and purposeful lunging is a great horse-training tool, helping to keep you safe and your horse, sound!

See Sidebar to this article: Lunging Dos and Don'ts

Related: Adjust Your Horse Stretches to Make Progress

Main Photo: Shutterstock/PIC by Femke