What Does The Future Hold?

By Li Robbins

Once upon a time animal acts were the big draw beneath the big top. Bears danced, elephants balanced on balls, and tigers leapt through flaming hoops — all in the name of human entertainment. Nowadays though, animal acts are no longer synonymous with “circus.” In Canada, according to the international wildlife protection charity Zoocheck, “wild animal circus acts are largely gone.” The reason for their demise is in part because they lost their “social licence to operate,” or SLO. SLO is the unwritten law that exists between the public and any industry — the term itself coined by Canadian mining executive Jim Cooney in 1997.

Decades of advocacy for circus animals drew the public’s attention to inhumane practices — elephants prodded by bullhooks, big cats being whipped, animals kept in tiny cages — and the public’s appetite for such “entertainment” began to erode. In 2017, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus went on hiatus. When it returned, in 2023, it was without the animals.

Some might dispute any parallel between the treatment of circus animals and horses in sport. However, incidents of inhumane practices in horse sport seem to be emerging on a regular basis of late. Case in point, a video that surfaced in July, just before the Paris 2024 Olympics. In it, Charlotte Dujardin, three-time Olympic gold medallist in dressage, repeatedly whips a horse’s legs with a lunge whip.

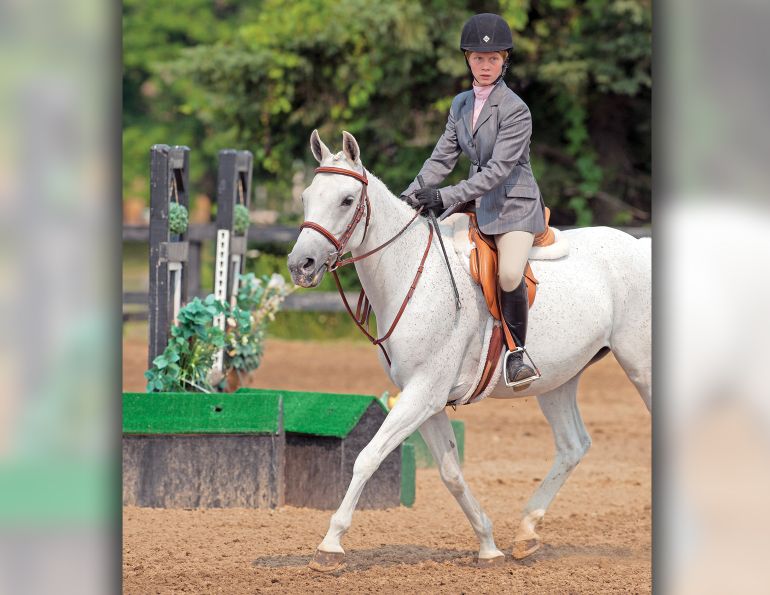

A social license to operate is an informal agreement where public approval allows an industry to operate with fewer restrictions. In horse sports, an SLO reflects the public’s acceptance of the sport and its practices. Maintaining societal approval is essential for the future of equestrian sports. Photo: LottaVess

The video sparked a firestorm, not just in equestrian press but in the mainstream. The Reuters story that ran in the Globe and Mail, for example, inspired comments like, “Frankly, isn’t the whole idea of riding around on a horse doing ballet a bit cruel?” and “We should let them [horses] live their lives and stop abusing them through forced performances and whippings.” Opinions came thick and fast and spread nearly instantaneously, pointing to one of the reasons for the growing focus on SLO, as Pippa Cuckson, who has written extensively about equine welfare in horse sport, points out.

Related: The Role of the Chain in Horse Handling and Training

“I am sure that in past times, people had misgivings about equestrian practices, training methods, and traditions but felt isolated and too scared to speak out,” says Cuckson. “Social media has put hundreds of thousands of like-minded folk in touch with each other, and collectively they have found their voice.”

The impact of that collective voice is as yet unknown, although the focus on SLO has surely contributed to increased talk about the ethics of riding horses at all. Cuckson says that it’s also drawn attention to “the random enforcement of welfare in the regulated sports.” But there’s still a considerable disconnect between those involved in horse sport, and those who are not.

“As far as elite level sport is concerned, there is still no mechanism for communication between the governing bodies and the numerous campaigning groups that have a vast following on social platforms,” says Cuckson. “They roll along on parallel tracks. The governing bodies are on the one hand painfully aware of public opinion, but not to the point it is impacting decision-making yet.”

As the governing bodies of horse sport struggle to come to terms with SLO, horse sport’s SLO continues to wane, in no small part due to that most public-facing showcase: the Olympics. The Dujardin video leak, coming as it did days before the Paris games, inextricably linked the two, and caused Dujardin’s withdrawal from competition, provisional suspension by the Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI), the loss of sponsors, funding, etc. It didn’t help horse sport’s cause that a horse-abuse scandal at the previous games (the Tokyo 2021 Olympics) was still fresh in the public’s mind.

Just days before the Paris 2024 Olympics, the equestrian world was rocked when a video surfaced showing three-time Olympic gold medalist Charlotte Dujardin using a lunge whip repeatedly on a horse’s legs during a training session. Here Dujardin is shown competing with Valegro in the Grand Prix Freestyle at the World Equestrian Games in Normandy in 2014. Photo: Clix Photography

In that instance, a horse in the equestrian segment of the pentathlon was whipped, spurred, and whacked in the haunches by the rider’s coach, captured on a video that went viral. Viewers were horrified, and Olympics’ organizers took note — as of the LA 2028 Summer Olympics riding will no longer be part of pentathlon. Pentathlon equestrianism is scarcely Olympic-level show jumping (the sport is also not overseen by the FEI), but members of the general public are unlikely to concern themselves with such distinctions. Horse abuse is horse abuse. Inevitably, an occurrence like this leads some to conclude that all equestrian sport should be removed from the Olympics.

The Dujardin incident must have made International Olympic Committee members’ stomachs clench, and not just because of what they saw on the video. After all, in the ramp up to the Paris games a French parliamentary study group on equine welfare announced that the Paris Olympics would be “a model of equine well-being.” As it turned out, they weren’t. Carlos Parro, a Brazilian eventer, was given a yellow warning card after he was seen riding his horse in rollkur (excessive and harmful hyperflexion of the horse’s neck) during a training session. Dressage was called out by media for sightings of “blue tongue,” a condition caused by oxygen shortage (in turn often associated with rollkur).

The Parro warning was issued following a complaint by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), and while PETA’s reputation itself is not without controversy, the organization is undeniably influential. Besides, growing concern over equine welfare in sport is far from originating with PETA alone. In the wake of the Tokyo Olympics the organization World Horse Welfare hired an independent market research firm to survey both the general public and equestrians about SLO and horse sport.

The key findings from surveys in 2022 and 2023 showed that 60 percent of the general public wanted more safety and welfare measures in horse sport, with 40 percent believing horses should be used in sport only if welfare concerns were improved. One in five or 20 percent did not support the involvement of horses in sport under any circumstances. Equestrians surveyed held similar views to the general public.

The FEI also stepped up its own equine welfare efforts following the Tokyo games, creating an “independent Social Licence Commission” (later renamed the Equine Ethics and Wellbeing Commission) in order to “address societal concerns related to the use of horses in sport.” Not everyone was sold on the FEI’s intentions — there were social media mutterings about the equestrian equivalent of “greenwashing” — given that the FEI does not have a stellar reputation for enforcing welfare rules already on the books. Explanations as to why this is are multiple, but Cuckson offers two.

Related: Concerning the Ethics of Riding Horses

The controversial technique of rollkur, or hyperflexion of the horse’s neck achieved through aggressive force, is banned in International and Olympic sanctioned equestrian sports. Photo: iStock/Mishella

“Most officials get paid expenses but they are essentially volunteers and many build a nice lifestyle around officiating and travelling; that kind of judge will hope to be invited back, so may try not to rock the boat,” says Cuckson. “Moreover, there have been ample reports of judges not getting any support from FEI HQ when they do try to stand up to riders who object to being censured for rule breaches and or horse abuse.”

After the Paris games, the FEI announced a meeting of “stakeholders” in October of 2024 in order to discuss “the challenges currently impacting the discipline of dressage.” FEI President Ingmar De Vos was quoted as saying, “While many in our community recognize the urgency of the situation, others may not yet fully grasp the critical juncture at which equestrian sport currently stands.” The statement also reiterated the need for competitors to act as “guardians” for their competition horses, improving standards of safety and care, a nod to its own “Be A Guardian” initiative, which was announced before the Paris games (and before the Dujardin video leak).

Being a guardian, according the FEI, means “our focus shifts to what is best for the horses, recognising them as unique and valuable beings deserving of human protection, trust, and respect.” In other words, welfare first, sport second. The idea that such a focus shift is needed is telling — one would have hoped that “welfare first” for horses was already a given, not just in the world of elite sport, but in any discipline, or, for that matter, no discipline at all. Horse sport may have the current spotlight, but inevitably a loss of SLO could have an impact on all human interactions with horses.

Dr. David Marlin, president of the National Equine Welfare Council, underscored the latter in a 2023 presentation titled “Could the government stop us from riding our horses?” in which he noted that there has already been a loss of SLO connected to horse-human undertakings, for example fox hunting, the ban on jump racing (steeplechase) in South Australia, not to mention Olympic pentathlon.

As equestrian sport involves the use of an animal that the public perceives as particularly vulnerable, society’s acceptance of equestrian sport and its related activities has come under increasing scrutiny. Maintaining our social license to operate in the horse industry requires our commitment to an ethical, proactive approach to equine welfare. Photo: Shutterstock/Hanzi-mor

Marlin believes that to turn the tide of horse sport’s diminishing SLO there must be significant change from the inside out, which in turn may require providing people with more evidence-based information about harmful practices such as rollkur, since it’s “much harder to argue with data.” But whether evidence- or opinion-based, the future of horse sport’s SLO comes down to how people involved in sport respond to the public’s concerns.

Related: Horse Safety and Trust: Rethinking How We Train

Animal acts in circuses once featured trained animals — lions, tigers, elephants, horses, and others — performing tricks like jumping through hoops, balancing on small platforms, or standing on their hind legs. These acts were designed to amaze audiences by showing exotic animals in controlled, human-like behaviours. Historically, these acts represented a thrilling blend of human mastery and spectacle, drawing large crowds eager to see rare animals up close.

However, changing attitudes toward animal welfare have made these acts a thing of the past. Concerns grew around how animals were trained and treated, as many were kept in restrictive environments, transported frequently, and subjected to stressful conditions. This led to public outcry, changing perceptions of animals’ roles in entertainment, and stricter animal welfare laws in many regions. Today, most circuses have replaced animal acts with performances by acrobats, magicians, and clowns, preserving the sense of wonder without involving animals. This shift reflects a broader societal movement toward respecting animals’ well-being and prioritizing ethical treatment. Photo: Shutterstock/Norenko Andrey; Photo: Shutterstock/Alexmak7; Photo: Shutterstock/Norenko Andrey

“We need a change in attitude within equestrian sport,” says Marlin in his presentation, adding that all those who have horses have a responsibility for the future of not just horse sport, but the owning and keeping of horses, period. It remains to be seen whether enough horse people take on that responsibility — and whether they do so in time.

Related: Tough Question: What are the top three issues facing the horse industry in Canada?

Related: How to Support Your Horse Through Change

Main photo: Shutterstock/Sychov Serhil