By Tania Millen, BSc, MJ

The gap between amateur and professional competitors is common in Canadian sports. Weekend skiers have significantly less skills than athletes on Canada’s ski team. Amateur hockey players don’t make Canada’s Olympic team. It’s the same in horse sports. Tiers of riders have developed as equestrian sports have become more technical. Upper-level horse sports are primarily the purview of professional and elite riders while amateurs play at lower levels.

“I don’t think it’s possible, today, to work downtown on Bay Street all day, ride one horse at night, and then go to the Olympic Games,” says Jacquie Brooks, a two-time Canadian Olympic dressage rider who coaches riders and trains horses while she brings along her own upper-level mounts. “But I’d love to be proven wrong!”

Amateur riders are just as passionate about their sport as professionals, but these days it seems that only professionals reach elite levels of competition. Elite riders are paid to ride and compete horses owned by those with deep pockets while amateurs generally work in non-horsey careers to pay for their equestrian passion. So, do amateur, professional, and elite riders face similar challenges, or are thre barriers between them? Four riders share their thoughts.

Time and Experience

“Even if an amateur rider had a wonderful horse, I think there would be a breakdown somewhere en route to the top because they just wouldn’t have enough experience,” says Brooks.

That’s understandable, considering an amateur might only be riding one or two horses per day — far fewer hours in the saddle than a professional. Competitive success depends on the talent of both horse and rider.

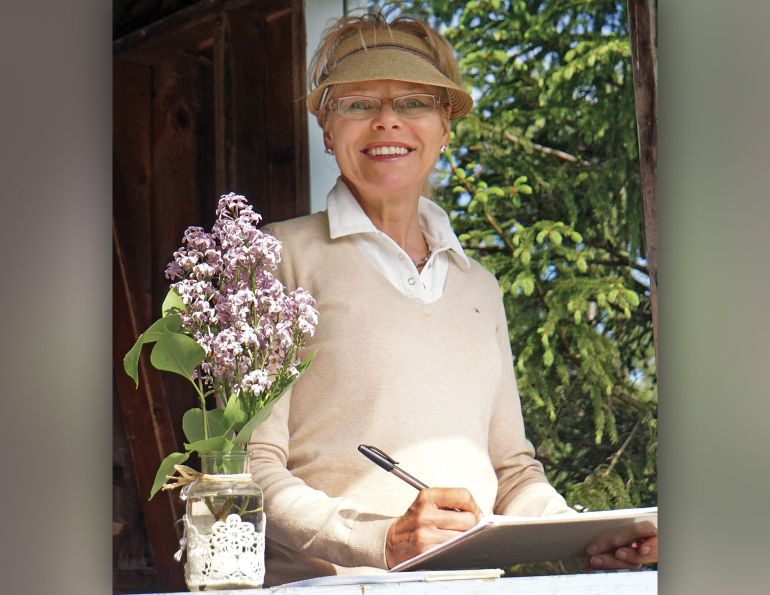

Two-time Olympian Jacquie Brooks thinks it’s no longer possible to work full-time all day, ride one horse at night, and get to the Olympic Games. “But I’d love to be proven wrong!” Brooks is shown riding the 2011 Oldenburg gelding, Te Amo QOS, sired by Totilas. Photos: Cealy Tetley

“I’m a prime example,” says Brooks. “I came into the sport late. I was very lucky with one of my horses and so I was on the Pan-American Games team and then the Olympic team within a crazy short amount of time after starting the sport. But I had done many sports at elite level before, so I knew how to compete at an elite level, and I knew how to train at an elite level. Plus, I had a very talented, straightforward, easygoing horse.”

Related: The Magic of Sport Horse Syndicates

Related: How to Be a Better Barn Boarder

In dressage, three-day eventing, and show jumping, riders are eligible to compete at any level provided they’ve qualified for the class. That means amateurs regularly compete against professionals when they choose to enter classes which aren’t specifically for amateurs.

“The divisions where I compete are the highest in the sport, nationally,” says Luanna Veldman, a 26-year-old Canadian amateur based in Ontario, who show jumps at 1.4 metres. “The majority of the riders are professionals who are competing two or three horses whereas I’m riding one horse that I’ve developed since he was four years old.”

Luanna Veldman trains every day and competes against show jumping professionals in Canada, but also has a full-time job. Her horse is talented enough to compete at a higher level, but her budget does not allow for the international travel needed to do so. Photo: Laurel Jarvis

That means Veldman competes against professionals who are sharper than she is because they’re competing more often, plus they’re advancing their riding skills faster due to their increased riding time.

“People say to amateurs, ‘this isn’t a living for you, it’s just a hobby,’” says Veldman. “But I take the sport very seriously. I go to the barn every single day. I train. I put in as much work as a professional, but I have a full-time job. So having to balance that and then try to compete against people who are riding for a living is hard.”

Related: Understanding Equestrian Canada's Coach Status Program

Related: 10 Tips to Help You Build a Better Barn Business

“There’s nowhere to go from here, unless I start traveling,” she explains. “I don’t have the opportunity to gain 1.45 metre experience staying in Ontario. My horse could do it, but I can’t afford to travel internationally. It’s a tough pill to swallow sometimes.”

Veldman’s challenge is to continue advancing her riding skills while staying near home and being happy with the choices she’s made, knowing that her horse is talented enough to compete at a higher level.

Cutting and reining competitions also have open classes where amateurs could compete against professionals if they chose to. However, not many non-professionals go that route. Instead, they stay in their lane, competing in classes specifically for novices and non-professionals. Classes are further divided by how much prize money the rider has won in their lifetime.

“I think [having class divisions] is an incentive because you end up competing with people that are more like you,” says Brad Pedersen, a professional cutting horse trainer who operates Pedersen Training Centre in Lacombe, Alberta. “Amateurs don’t have to show against pros, so that makes it fairer, really.”

Professional cutting horse trainer, Brad Pedersen, says to get to the top of the cutting world, you have to leave Canada because the top horses and highest money shows are in the southern United States. Photo: Larissa Price

“Different reining classes give people who are new to the sport, or maybe not riding as talented a horse or just not that strong of a rider, a chance to compete,” says Monique Noble, an amateur reiner who has competed for over ten years in Alberta. “But anyone can go in open classes, so that’s where you see a higher level of riders and trainers competing.”

However, the costs of competing, training, and purchasing horses, tack, and transport for horse sports can be prohibitive.

Related: Leaping the Gap - From Riding Student to Professional Equestrian

Related: How to Find Money for Horse Sports

Money Matters

“Money will limit both amateurs and professionals soon, and I think the amount of money needed is putting people off,” says Brooks about the dressage world. “That’s what’s going to limit the number of people in the sport. I think the cost is what’s going to kill horse sport.”

“Once you get to the higher levels, you have to be able to buy higher level horses, and they’re very expensive,” says Noble about reining horses. That’s a limiting factor, and renewed interest in reining due to COVID-19 and the Yellowstone television series have pushed horse prices even higher.

Amateur reiner Monique Noble (above/below) enjoys watching the professionals and elite riders. “We all aspire to be that good and that flawless and that fearless.” And when the top riders make a mistake she says they become more relatable, which unites competitors and builds support for all levels of competition. Photos: GK Photos

Some horses are amateur-friendly to ride, and others are so challenging that only professionals can ride and train them. Not all professionals choose to bring along their competitive partners. Some professional riders purchase horses that are already trained to top level, then advance their aspirations — and those of the horse’s owners — with ready-made horses. That pushes horse prices higher, too.

“Horse racing is called the ‘sport of kings,’” says Noble. “Well, any upper-level horse sport is a sport of kings.”

Although increasing costs may have dampened some ambitions, many amateurs and professionals continue to pursue their passion.

Challenges and Opportunities

“A lot of amateur riders are quite happy traveling around and competing for the fun of it,” says Veldman. “But the ones who are serious get to a stage where they have to make a decision [whether to become professionals or not].”

“I think amateur riders that get frustrated are ones that can’t afford to be doing it full-time, aren’t good enough for the team, are limited by money, or can’t put their whole life into it — if that’s their ambition,” says Brooks.

Pursuing riding as a profession is a tough decision but financial backing helps, as does talent, connections, a good reputation, and choosing to live where your chosen sport is prevalent.

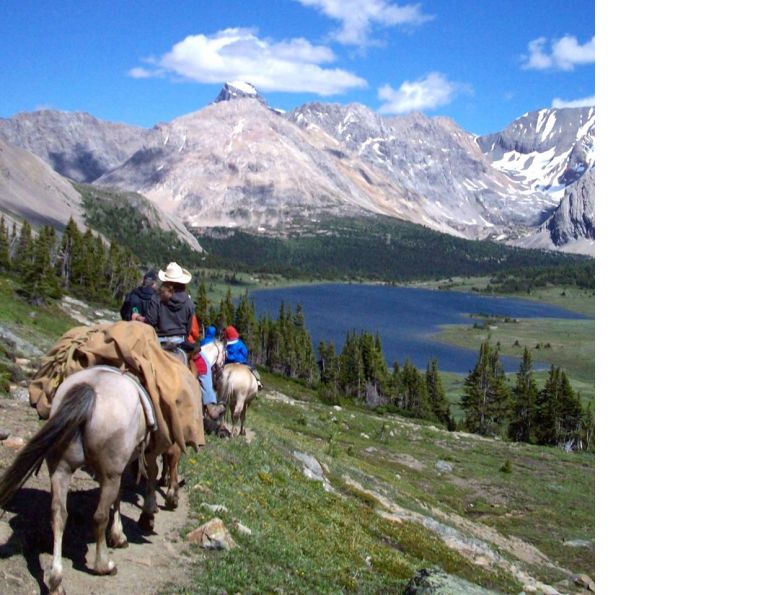

“The better rider you are, the more horses and the better the horses you’re going to get,” says Pedersen. “You basically have to live in the [United] States and have a great reputation to get to the top of the cutting world. The top horses and highest money shows are in the southern United States, so you really have to be down there if you want to be in the top 15 cutting riders in the world.”

Fortunately, being the best in the world isn’t everyone’s ambition. There are plenty of amateurs enjoying their chosen sport and professionals making a living in small towns across Canada.

Places for Everyone

“There’s room for everyone in horse sport,” says Brooks. “Seeing the pros is good for sport. I think it inspires people.”

Noble agrees. “It’s so exciting to watch the pros,” she says. “We all aspire to be that good and that flawless and that fearless. Just to watch that level of riding is spectacular because the horses and riders are amazing, and the speed and technicality and grace of their runs is magical.”

Bringing a piece of that magic into everyday amateur riders’ lives is how upper riders and elite horse sports can ensure that those within the industry remain engaged.

“I enjoy watching FEI [International Equestrian Federation] competitions because I’m always looking for ways to improve my riding,” says Veldman. “You can learn so much from those riders, and quite frankly, a lot of the time I’m competing against them. So, for me it’s very beneficial.”

According to Noble, when professionals and elite riders make mistakes in competition, they’re actually more relatable to riders who will never compete at their level. Knowing top riders aren’t invincible breaks barriers, unites competitors, and helps build support for all levels of competition.

“We have to make sure that horse sports remain accessible,” says Noble. “They can be intimidating for people who don’t have the ability to buy expensive horses, so I think it’s important that the horse industry continues to support lower-level shows. As long as those shows are affordable, horse sports are going to be around for a long time.”

Related: Professionalism in the Horse Industry

Related: Finding Paths to Success for Equestrian Youth

Main Photo: Amateur show jumping rider Luanna Veldman. Credit: Laurel Jarvis