By Jec A. Ballou

Most riders who “earn” their spurs can recount at least a few stories about their potential harm or have known horses with ribcage scars and damage from overuse. Whether spurs are inherently good or bad, however, depends on numerous factors including an understanding of their respective role in different disciplines.

While their specific purpose varies between English and Western traditions, spurs are in both cases meant strictly for refinement. When spurs become part of a rider’s everyday outfit versus a carefully curated tool, the result can oppose the very purpose for which they are intended, and in some cases damage nerves and connective tissue that impacts the whole body.

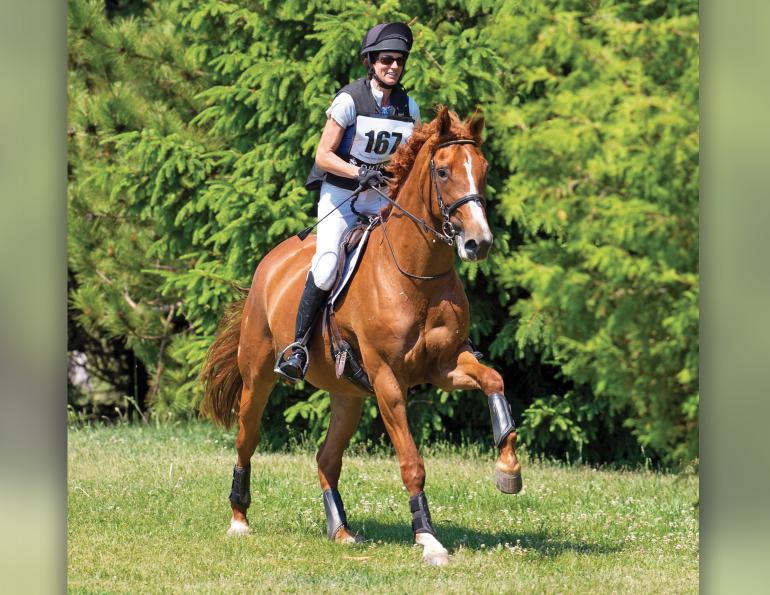

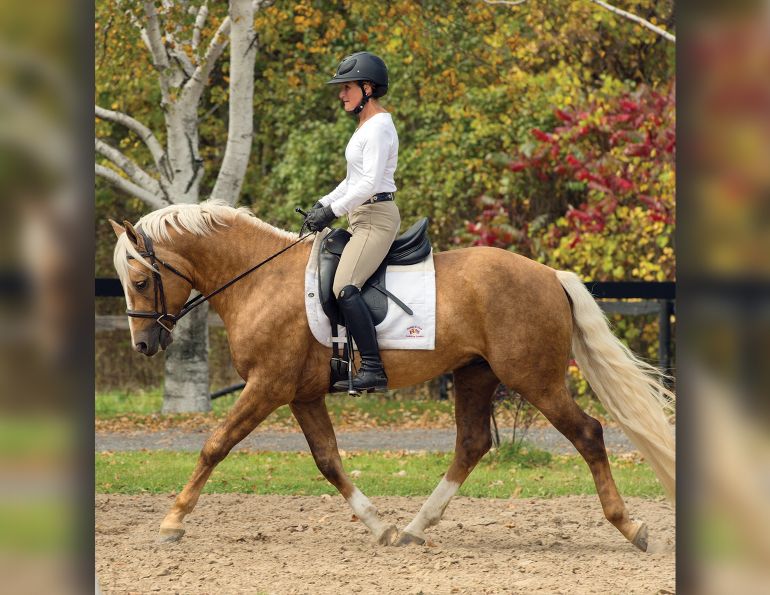

Broadly speaking, historical differences between Western and English uses of spurs can be summarized as shaping versus energizing. These preferences reflect variations in training traditions, seat styles, and rein contact. English riding favours spurs to quicken a horse’s response to leg aids and to increase energy. They are used momentarily and then ceased. For example, a dressage rider might use a flick of the spur to hasten hind leg engagement for a more expressive trot. Or she might touch briefly with the spurs to energize a gait and move with more speed if the horse does not respond sufficiently to leg pressure.

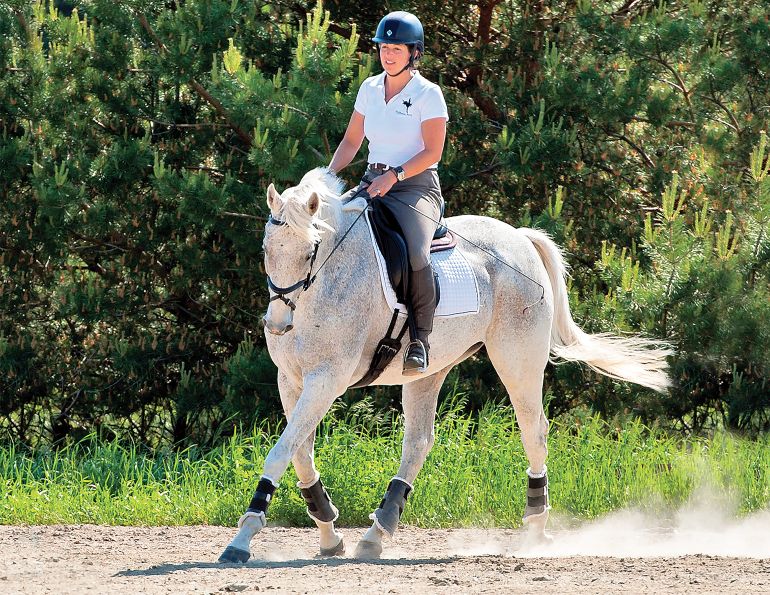

In Western riding spurs are commonly used to influence the horse’s body carriage, direction, and maneuverability. For instance, a rider might use a sliding or gently rhythmic touch of spurs to ask the horse to lift its back and tuck its pelvis. The rider might frequently — but softly — brush one or both spurs along the horse’s sides to flex the ribcage or encourage collection during a downward transition.

Related: Equine Learning Theory: Why Every Rider Needs to Understand It

In Western riding, spurs are often used to shape a horse’s body carriage, guide its direction, and enhance manoeuverability. Photo: iStockDGPhotography

Understanding these variations in training traditions is part of how a rider uses spurs correctly. First, knowing a given horse’s background will help answer the question of whether and how you should wear spurs, or not. An English rider would not want to climb on a former Western performance horse, for example, and use her spurs hoping to create a faster trot. She might get the result she wants, but there is the greater likelihood that she will create confusion and eventually a dull response to leg aids in general.

In fairness to each horse, we should stop and ask what it already knows regarding the meaning of spurs or what we hope to teach it within the context of its discipline. Moreover, it is worth underscoring the simple fact that a rider should not use spurs for everything — manoeuverability, speed, posture — if the desired outcome is subtler, clearer communication.

Separate from historical traditions, the question remains whether spurs need to be used at all, especially since they can hurt the horse. Based on a survey by the American Horse Council, nearly 60 percent of equestrians reported observations of spur misuse or abuse. Likewise, a study published in the Journal of Equine Veterinary Science reported that horses subjected to excessive spurring had elevated cortisol levels, indicating heightened daily stress. However, in recent years a study by the International Society for Equitation Science suggested that when used judiciously, spurs may not negatively impact a horse’s welfare.

Certainly, a case can be made against widespread and thoughtless use of spurs. And yet it bears repeating that they are a means of giving precision to a rider’s cues. Clarity and precision of communication with horses is arguably always worth pursuing. On this note, historical horse training books emphasized the use of spurs only for advanced riding. When worn by impatient or ill-tempered riders, or those with unsteady leg positions or still developing cue timing, spurs become cruel to the horse.

Related: Could Your Saddle Be Causing Behaviour Problems?

Archeological evidence of bone and bronze spurs dates to the fifth century BC. By the Middle Ages, they became symbols of chivalry, awarded to soldiers as they graduated from squire to knighthood. During formal ceremonies, these soldiers were festooned with spurs to denote their higher rank. Later, as the horsemanship influence of Spanish Vaqueros spread widely, spurs found their way into advanced riding techniques with the style resembling today’s roweled and adorned Western ones. Their purpose was to serve as an extension of the rider’s leg during refined manoeuvres.

The prick spur (top), the earliest known type, featured a pointed goad attached to side arms or a heel plate. The first versions were likely simple thorns fastened to the heel, later evolving into metal forms in antiquity. Common throughout the Middle Ages, prick spurs remained dominant until the mid-14th century, then were gradually replaced by rowel spurs (bottom). In the age of knighthood, spurs became potent symbols of chivalry, presented as part of the ceremonial honours marking a squire’s elevation to knight.

In clinic settings, I often encounter students who prefer to avoid spurs out of a desire to be as gentle as possible. Occasionally, though, these same riders resort to incessant leg cues to gain responses from their horses. They may even begin banging their legs against the horse’s side or adding pressure each time they squeeze their legs. These scenarios, provided the rider has a balanced and quiet leg position, beg the question whether it might be kinder to use a spur to create less noise and nuisance on the horse’s sides. Used as intended, they give a rider the option to be softer and intermittent, not louder and more repetitive, with leg cues.

Related: How to Find the Perfect Horse Riding Gear

Obviously, their design also determines whether spurs feel helpful as opposed to irksome to the horse. A long shank and sharper points increase severity. Most English competitions mandate minimal shank lengths and blunt ends. Amongst popular roweled spurs in Western riding, a greater number of points on the rowel reduces severity by allowing it to roll against the skin instead of jab.

In Western roweled spurs, more points on the rowel reduce severity by allowing it to roll over the skin rather than jab into it. Photo: iStock/zim86

Even with a humane style of spur, tactful riders remain mindful of the damage that can be caused to the horse’s fascia either from direct trauma or from scarring that develops over time. This damage can lead to adhesions in connective tissue and consequently restricted movement, heightened sensitivity and discomfort, and even alterations in the horse’s gaits.

In summary, spurs should not automatically be part of a rider’s daily wardrobe. Any given day, a rider should ask what he or she hopes to accomplish with the horse and whether that task requires additional refinement. And then she must ask whether her leg control and timing are suitable to wear spurs.

Blog - Equine Fitness & Performance with Jec A Ballou: Learn Three Things: Carrying a Whip

Related: The Science of Tack and Training Aids

Related: Does Your Horse Need a Lot of Leg?

Photo: iStock/Patrick Kerwin