By Dr. Colin Scruton, BVetMed, MS, MRCVS, DipACVS

Hind limb problems can be confusing to identify and even harder to diagnose in horses. Some conditions can lead to mechanical deficits or difficulty in certain movements without causing the classic pain-associated lameness. Stringhalt, fibrotic myopathy, shivers, and equine polysaccharide storage myopathy (PSSM) are four distinct diseases in horses that result in gait deficits. Accurate differentiation of these conditions allows for the most effective management to be used.

Stringhalt

Stringhalt is a disease characterized by sudden hyperflexion of the hind limb at the beginning of the stride. The limb is seen to jerk towards the abdomen in the early phase of the stride. This is most commonly seen at the walk and can be intermittent or every stride. The degree of hyperflexion can range from very mild to so severe that the front of the fetlock actually hits the abdomen. Horses with stringhalt may have difficulty with manipulation of the hind limb and can be a challenge for the farrier.

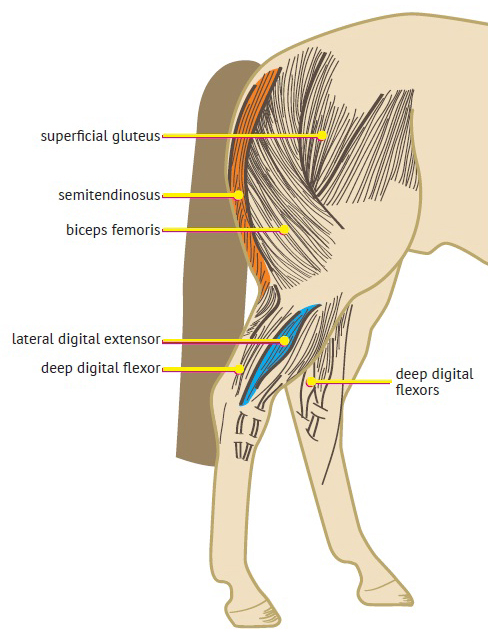

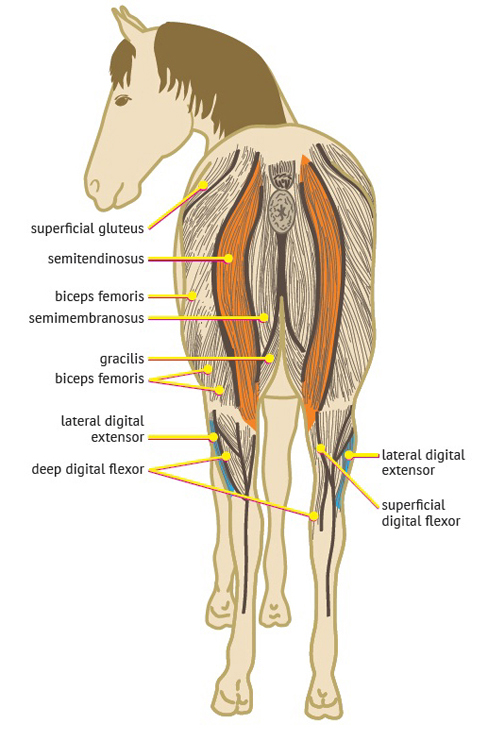

One form of stringhalt is associated with damage to the lateral digital extensor muscle.

There are two forms of stringhalt. The first affects isolated horses and is often associated with damage to the lateral digital extensor muscle and tendon. This form of stringhalt commonly affects one hind limb but occasionally is bilateral. Some studies have shown that there is associated nerve damage but it is not known whether this is the cause of the condition or secondary to trauma. Horses with the intermittent form of the disease do not typically recover spontaneously. In one study using rest and rehabilitation one out four horses recovered, two improved, and the fourth showed no improvement. Classic treatment for this form of the disease involves surgical removal of the tendon and bottom portion of the lateral digital extensor muscle.

The second form of stringhalt is often bilateral and occurs in outbreaks when horses consume toxic weeds in times of drought. Commonly called Australian stringhalt because of the frequency of its occurrence in Australia and New Zealand, it has also been seen in California, Washington State, and Chile. Diagnosis involves observation of the individual horse and recognition of the classic signs. Treatment of the Australian form of the disease consists of removing the horse from the affected pasture. In both forms of the disease, prognosis is guarded to favourable with most horses showing some improvement; however, the overall degree of improvement in horses with stringhalt is unpredictable.

Fibrotic Myopathy

Fibrotic myopathy is described as having the opposite hind limb gait to stringhalt. Horses show a shortened cranial (late) phase of the stride with a slapping of the foot toward the ground. Again, this is a condition seen most obviously at the walk.

Fibrotic myopathy is the result of scar tissue formation within the semitendinosus muscle.

Fibrotic myopathy is the result of scar tissue formation within the semitendinosus muscle. This may occur secondary to repeated injuries from activities such as barrel racing or reining, when there is chronic stretching of the muscle. It may also be the result of an acute injury such as falling on the butt bar of a trailer, slipping on ice or mud, or even a training injury. Repeated intramuscular injection is an uncommon cause of the condition.

Diagnosis involves careful palpation of the caudal aspect of the hind limb to feel the scar tissue in the muscle. The gait is also characteristic of the disease.

Treatments for the disease are surgical. The scarred portion of muscle can be transected using a direct incision in the standing sedated horse. This method has limited success and is associated with a high level of recurrence and reformation of scar tissue. With the horse anesthetized, the tendon of insertion of the semitendinosus muscle can be cut allowing for more stretch in the muscle. Physical therapy involving stretching and walking over elevated objects is critical to success. Overall success is variable with some horses showing recurrence of signs after initial improvement.

Shivers

Shivers or shivering is a neuromuscular disease that affects the hind limbs of horses – particularly draft horses, although it has also been reported in Warmbloods and other breeds. A study in Belgian draft horses found that 19 percent of individuals showed signs of shivers. Shivers is seen in horses of any age starting as early as one to two years of age.

Diagnosis of the classic case of shivers is simple; however, signs may be intermittent or occasional. Typically, horses show intermittent spasms of one or both hind limbs and the tail. Mildly affected cases show jerky movement of the hind limbs and elevation of the tail. The tail elevation component of the syndrome can be very variable. In more severe cases the hind limb is lifted suddenly and held trembling when the horse is backing up. The muscles and tail may be seen to quiver for seconds to minutes before relaxing again. One of the first signs often noticed by owners is that the horse tends to snatch its foot when it is being picked out. The farrier may notice that the horse quivers when the shoes of the hind feet are being nailed and the condition may progress to the point that the horse is no longer able to be shod. When moving forward, the signs may be apparent for only the first two to three strides but horses with advanced signs may be able to back up only a step or two. Baseline blood work is usually normal in cases of shivers.

Shivers is a neuromuscular disease most commonly found in draft horses, although it has been reported in Warmbloods and other breeds. One study of Belgian draft horses found that 19 percent of the individuals showed signs of shivers. Photo: Flickr/Richard (The_Gut)

The underlying cause of shivers has not been determined but there are many possibilities. The muscle spasms may be caused by a neurological disorder, but detailed studies on horses with shivers have failed to identify a neurological cause. In the past, an underlying muscle disease was thought to cause shivers but this has been shown not to be the cause. It is common for horses with shivers to have muscle storage disease but these are separate conditions seen in the same animal. Shivers is thought to have a familial tendency but, although a genetic cause has been suggested, it has not been proven. Other potential causes that have been proposed are infections or toxic reactions, and trauma, but neither have been proven to cause shivers.

There is currently no treatment for shivers. Horses with both shivers and equine polysaccharide storage myopathy (PSSM) may show some improvement in signs when treated with a high fat, low starch diet. Vitamin E supplementation appears to be very important for horses with shivers. Horses with shivers should remain in work and receive constant turnout as it is difficult for them to rebuild muscle mass after a period of time off. The prognosis for horses with shivers is generally poor as this is a slowly progressive condition, and the prognosis for long term athletic ability is grave.

Equine Polysaccharide Storage Myopathy (PSSM)

Equine PSSM is a muscle disease characterized by the storage of both a normal sugar (glycogen) and an abnormal sugar (polysaccharide) in the muscle of horses. The disease most commonly affects Quarter Horses, Paints, and Appaloosas, although it has also been seen in many other breeds including drafts, draft crosses, and Warmbloods. There are two types of equine PSSM.

Type 1 PSSM is seen in over 20 breeds including Quarter Horses and related breeds, Morgans, some draft breeds, and some Warmbloods. This type is caused by a gene mutation resulting in increased enzyme production. There is a genetic test available for Type 1 PSSM.

Type 2 PSSM is found in Quarter Horses, Arabians, Thoroughbreds, and possibly other light breeds. Horses with Type 2 PSSM do not have the genetic mutation that causes Type 1, allowing the two types to be distinguished using genetic testing.

Horses with PSSM tend to be easy keepers and are often overweight. Adherence to a strict diet, including reduction or elimination of access to lush pasture, is very important. Photo: Flickr/Sino Merikallio

The signs of both forms of PSSM are those associated with horses tying-up, namely muscle stiffness, sweating, and reluctance to move. Signs are seen most commonly when a horse returns to training after a period without work and are often seen after only light work (10 to 20 minutes). The horse may seem lazy, have shifting lameness or flank tremors, and tense up the abdomen during an episode. The horse becomes stiff, sweats profusely, and the muscles over the hindquarters become particularly tight. In severe cases the horse may produce dark coloured urine. This can be dangerous if the affected horse becomes dehydrated as it may result in kidney damage.

To determine if a horse has had an episode of tying-up a blood sample can be tested for muscle enzymes. In typical cases the muscle enzymes are markedly elevated. Often the muscle enzyme levels will return to normal within a few days. If a horse suffers from PSSM the muscle enzymes will typically remain elevated for weeks. Exercise testing can be used to test if a horse is prone to tying-up. Blood is sampled four to six hours after exercise to assess for mildly elevated muscle enzyme levels. This testing is useful to assess for tying-up but is not a specific test for PSSM. Muscle is very good at healing and will usually heal without scar tissue formation three to four weeks after an episode of tying-up.

Diagnosing PSSM involves a combination of genetic testing and/ or muscle biopsy when the disease is suspected. In Quarter Horses it is recommended that blood or hair be submitted for genetic testing for Type 1 PSSM. If it is negative and the disease is suspected, then muscle biopsies should be submitted. In drafts and Warmbloods it is recommended that hair and muscle are submitted at the same time for evaluation. In Thoroughbreds it is recommended that just muscle is submitted.

Managing horses with PSSM involves a combination of rest, careful exercise, and appropriate diet. If only diet is modified, approximately 50 percent of horses show improvement, whereas if diet and exercise are modified, 90 percent of horses show improvement.

Strict adherence to diet is very important in horses with PSSM, but allow at least a couple of weeks for the horse to become accustomed to a new diet. Most horses with PSSM are easy keepers and may be overweight at the time of diagnosis. Feeding hay with a low non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) content, in the amount of one to one and a half percent of the horse’s body weight, can reduce weight. It is important to choose hay that has a NSC content of less than 12 percent. Using hay with an even lower NSC content (around four percent) allows more fat to be added to the diet. It is important to test each batch of hay fed to horses with PSSM. This is simply done by taking a sample of the hay to most feed stores and having them submit it for analysis.

The type and amount of fat added to a horse’s diet depends upon the individual horse, its weight, and exercise intensity, although during periods of weight loss, feeding fat may not be necessary. The benefit of a low starch, high fat diet is less glucose uptake into muscle cells and more free fatty acids in the muscle fibres to be used as an energy source during aerobic exercise. Horses can also be fasted for six hours before exercise to increase free fatty acids.

After an episode of tying-up, paddock exercise should be commenced as soon as the horse will tolerate it. Horses with PSSM can be turned out with grazing muzzles if pasture is lush. Reintroduction to exercise should be gradual. The horse should be worked regularly minimizing days off, with a minimum of three weeks of walk and trot before canter is introduced. Once the horse has been reintroduced to exercise it is important to maintain regular exercise as it has been shown to be beneficial in minimizing muscle damage.

If you suspect that your horse is suffering from stringhalt, fibrotic myopathy, shivers, or equine PSSM, it is very important to consult your veterinarian for an accurate diagnosis and appropriate management plan.

Originally from Vancouver Island, BC, Dr. Colin Scruton graduated in 2000 from the Royal Veterinary College in London, England. He went on to complete a large animal internship at Washington State University, and an equine surgical residency at Colorado State University (CSU). After his residency, Colin remained at CSU as faculty for nine months running a surgery and lameness service, followed by a year of employment in a similar capacity at the University of Glasgow. In 2006, Colin returned to the Comox Valley on Vancouver Island where he opened Equerry, a specialty equine surgery and sports medicine practice. www.equerry.ca

Main Photo: Pam MacKenzie Photography - Stringhalt is characterized by the sudden hyperflexion of the hind limb. In severe cases, the front of the fetlock may actually hit the abdomen.