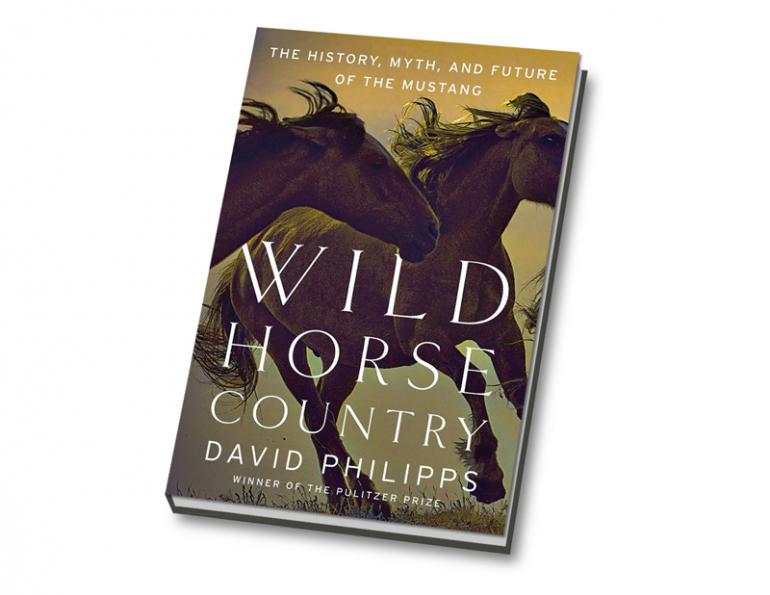

The History, Myth, and Future of the Mustang

By David Philipps, W. W. North & Company, Non-fiction, ISBN 978-0-393-24713-8, 368 pages, Hardcover, Kindle

Reviewed by Margaret Evans

“There were no wild horses in North America when the Spanish arrived,” writes author David Philipps. “Three centuries later when American settlers reached the West, horse numbers may have been in the millions. Mustangs on the Great Plains stretched from horizon to horizon. Whole areas of West Texas were marked on early maps with two words: wild horses.”

In his fascinating book, Wild Horse Country, published in October, 2017, Pulitzer prizewinner David Philipps traces the rich history of the wild horses whose ancestors evolved in North America 55 million years ago, disappeared from the continent at the end of the last Ice Age, then were reintroduced to their homeland by Spanish explorers.

“It was the quickest, most widespread, and most successful introduction of a species in the history of the world,” he writes.

But then, as he also points out, evolution can have a long memory. Grasslands today are pretty much the same as when ancient horses ran on them millennia ago. Despite being gone for some 10,000 years, that niche persevered.

“After developing together for so long, they still remember in their DNA what it was like to live together.”

Few wild animals grab the imagination as the sight of wild horses on the range running in a small band with a lead mare, fleet-footed foals, and a stallion hustling up the rear. The wild horses define American culture, American history, American literature through the writings of Zane Grey, and American movies Hollywood style.

Horses brought a profound change to Native Americans. Apache, Navaho, Comanche, Ute, Kiowa, Arapaho, Cheyenne, and many others all sought the status of being mounted warriors, and the desire for horses impassioned the desired for more. Horse stealing, Philipps writes, became a positive feedback loop. The more they stole, the more they needed to steal. The more they relied on raiding, the more they needed to raid. It became the age of the Horse Nations, which would last 200 years with the horse the most important article of their trade, a defining status, and the currency of the plains to be banked on as long as the blonde grass grew.

But dark clouds rolled in on the heels of the wild horses. Philipps’ narrative ventures into the dark side, remembering all those wild horses that served the dog food industry and went to slaughter by the thousands as animal rights activists voiced their outrage.

Today the management of the wild horse remains a dilemma. Philipps recounts in great depth the complications of managing wild horses, meeting the expectations of ranchers and hunters, state policies that keep up the need for predatory wildlife control, and the staggering economy of trying to maintain all of it in some semblance of balance. He points out, with raw common sense, that a lot of money could be saved and a lot of fragile land better maintained if predator control programs were dropped and mountain lions were left to keep horse numbers in check.

At many levels, wild horses still have a rich hold on all who cherish their freedom, their beauty, and their endurance through time. Yet their future trots a thin line between decisions on what to do with thousands of horses held by the federal government through their management by the Bureau of Land Management and the confrontational ideals of horse lovers, activists, ranchers, scientists, and all levels of government officials.

Wild Horse Country is a terrific read and it gives pause for thought on the history and our responsibility for such a cherished species.