Start Rewiring Early

By Annika McGivern

Habits are mental shortcuts created by our brain to reduce the need to make conscious decisions every moment of the day, which would require far too much time and processing power. By associating certain events and experiences with specific actions and responses, our brain can respond quickly and efficiently without our conscious “input.” For example, when a horse pins its ears and shifts its weight, we typically have moved out of harm’s way before we have had time to think about what we are doing.

The habitual response happens automatically and helps keep us safe. The brain is highly motivated to keep us safe, and therefore many habits are created by our brain to achieve this. While most of these habits are very useful (such as our body reacting to keep us astride a spooking horse, or the habitual instincts that make us brake when the car ahead unexpectedly stops or slows down), some are less useful, especially when we have big performance goals.

Meet a client of mine named John. He is a showjumper currently showing at 1.10m with a goal to reach 1.30m. His horse has the ability and so does John, but he had been stalling out at 1.10m for quite some time before working with me. Every time he tried to move up to 1.20m everything seemed to fall apart. His confidence severely knocked and he would retreat to 1.10m. Let’s look closely at John’s story to better understand the role of high-performance habits in helping us to move forward.

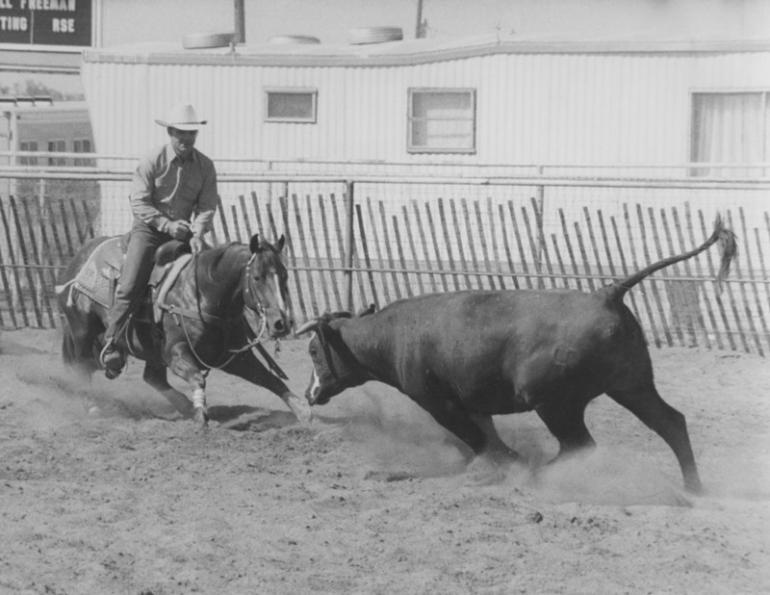

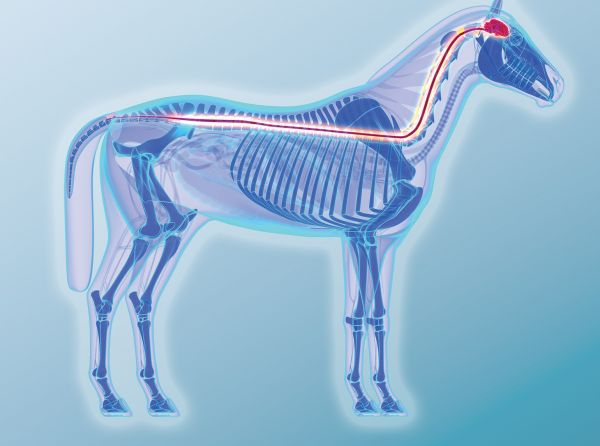

A habit of focusing on failures and playing them over and over in your mind will keep you in a self-critical state unable to move past the frustration. Photo: Shutterstock/Ebro

John was working hard towards his goal but he wasn’t getting enough traction to move him past his block. In my initial conversations with John we discovered the following:

John was extremely stressed about competing. He had moved up relatively quickly to 1.10m and now was deeply embarrassed by his perceived failure to progress. This stress was actively preventing him from thinking ahead and planning his competitive season, which meant he was managing his season in a very reactive way and had no real plan to follow.

Related: How to Build High Performance Belief Systems for Equestrian Athletes

Remember that competing is something you choose to do and learning and developing your skills allows you to grow as a rider. Photo: iStock/Henfaes

The stress and embarrassment John felt was also actively preventing him from reflecting on what happened at the shows. He expressed that he preferred to put the failures firmly behind him and not think about them at all.

However…

- It quickly became clear that John was constantly replaying the failures over and over in his mind, although he described this as unintentional and something he did not enjoy. It felt like a video he couldn’t turn off. This was keeping John in a very self-critical state of mind as he picked apart everything he had done wrong and chastised himself for it.

- John had begun to enter fewer clinics and shows, explaining that he felt it was all a bit too much and he was burning out. He had begun to fear he wasn’t cut out for the bigger classes and felt a deep sense of disappointment and shame in his seeming inability to make his goals a reality.

What do John’s habits have to do with turning around this difficult cycle? Remember, our brains form habits that keep us safe. Here, it is important to know that our brain, left to its own devices, often interprets stressful and high-pressure situations (such as competitions) as unsafe. Therefore, unless we take conscious control of our habits, we are likely to build habits that lead us away from pressure and discomfort. This can turn into a routine of backing away when pressure mounts, shutting down during competition, or choosing not to compete regularly.

John had formed four unhelpful habits:

- Not planning ahead and therefore responding reactively to what happens;

- Not learning from reflection;

- Engaging in highly self-critical self-talk that kept him frustrated and upset;

- Choosing to back away from any pressure and discomfort.

These four habits all came from John’s brain’s desire to keep him safe and protect him from the pain and discomfort of stress. However, these habits were not serving him or improving his well-being or helping him achieve his goals. It was time for John to work on rewiring his habits and responses to achieve a different outcome.

John’s New High-Performance Habits:

Self-compassion — John started to build an intentional habit of self-compassion. This meant that when he caught himself in negative and critical internal dialogue he paused, took a deep breath, and refocused on why this goal was important to him and how exciting, interesting, and challenging it was to have the opportunity to work towards such a goal. He reminded himself to soften his words (as if he was speaking to a friend) and his body (by intentionally relaxing and releasing tension).

Curiosity — Next, John practiced replacing frustration with curiosity. He made a new rule for himself that every time he caught himself feeling frustrated while riding or thinking about riding, he had to engage his curiosity and start asking questions. For example, if he felt frustrated remembering a difficult lesson, he would then have to get curious about that ride. What happened? What didn’t work? What could he do differently? How could he apply this idea in his next ride? Curiosity leads us from the spin of frustration to a problem-solving frame of mind. Part of the magic of curiosity is that in this new state of mind, the frustration usually vanishes completely.

Related: The Two Faces of Perfectionism in Horse Riding

By learning to replace frustration with curiosity you can move to a problem-solving state of mind. Photo: iStock/RossHelen

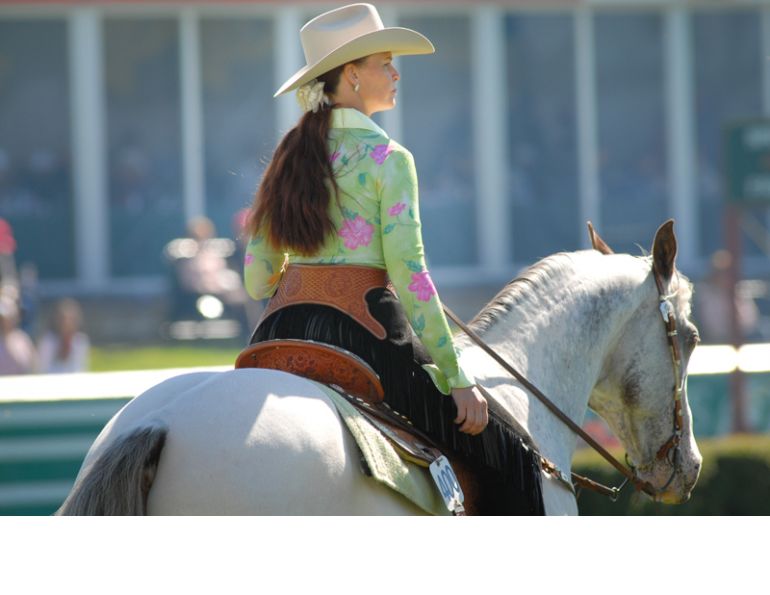

Looking ahead and regular reflection — The discomfort John was experiencing at competition was causing him to avoid thinking about the show in advance or reflecting on past competitions. However, not planning meant he was reacting emotionally when things went wrong and often making things worse. With practice, John began building the habit of detailed preshow planning and postshow reflection. He began to decide in advance how he would like to react to success and setbacks. This allowed him to stay more grounded at competition. Through regular reflection, he was able to recognise patterns and understand what contributed to a successful show versus what lead to setbacks.

Learn to love pressure — John had become overwhelmed by the negativity, pressure, and unease he was feeling. This caused him to instinctually retreat from challenges. Once John recognised this, he realised that his thinking about competing had been all wrong. It was not something he was forced to do but something he chose to do. He decided that if he was going to choose to compete it had to hold some sort of positive purpose. Through reflection, John recognised that deep down he loved the challenge of competing and finding out what he was capable of. He loved learning and developing his skills as a rider. Once John recognised that discomfort was a natural side effect of challenging himself, his mindset changed. He wanted more challenge and opportunities to grow in his life, which meant he wanted more discomfort. With this shift in mindset, he began to welcome the challenge of showing again.

To keep yourself grounded and better prepared for setbacks, think about the show in advance and reflect on successes and setbacks after the show. Photo: iStock/Abromova Kaeniya

How long does it take to change?

Have you heard that it takes 21 days to change a habit? This concept was popularised a while back by a famous piece of research that seemed to demonstrate just that. Since then, more research has shown that while we can change small habits in 21 days, such as drinking more water or journaling in the morning, reshaping deeper habits connected to our beliefs, identities, and fears take anywhere from three months to a full year. I see the truth of this in my work, with most clients feeling significant change after two to three months of focused effort. John had spent a long time practicing his old, unhelpful habits. About three months in, he expressed his amazement to me that, when he looked back at where he had been three to six months before, he truly felt like a different person. He was lighter and more energised, enjoying the challenges of his sport, and had moved into jumping 1.15m classes with consistent success. Most importantly, he believed in himself again. He believed in his ability to reach 1.30m. He knew it was just a matter of time and consistency.

Start early! Deciding today to implement the high-performance habits shared in this article means that you will have them firmly under your belt by the height of show season. Moreover, these habits will continue to serve you for years to come. I encourage you to invest time now to benefit your future self. You’ll be glad you did.

Related: The Mental Game - Sport Psychology for Equestrians

To read more by Annika McGivern on this site, click here.

Main Photo: Shutterstock/Thomas Marek