By Margaret Evans

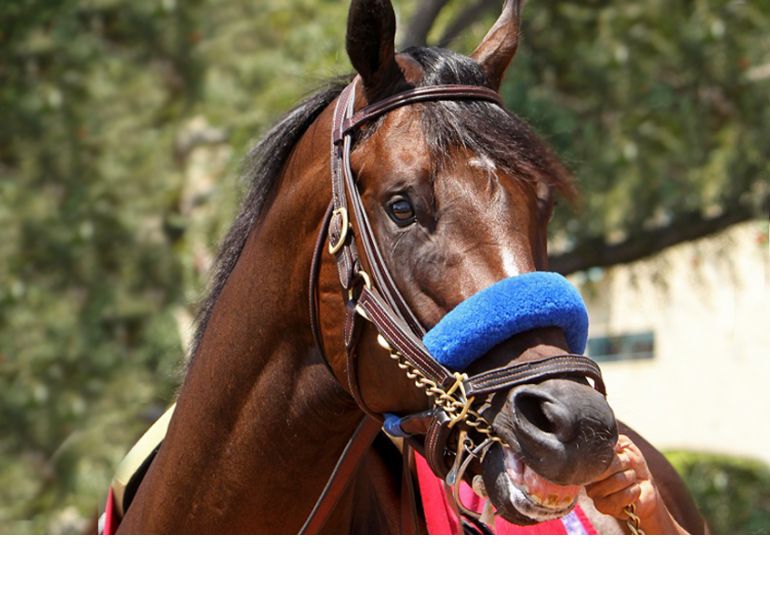

It was devastating when we lost Zona. At 32, our palomino Anglo-Arab, who had been a champion show horse on the prairies in her youth, was still pretty much the boss of the herd. Everyone deferred to her. Yet we knew there was something wrong. Her sharpness was dulled. Instead of eating her hay vigorously, she would nibble, then hesitate and stare off into the distance as though focusing on something only she understood. Typical of geriatric horses, she had lost some weight and her coat had gone curly. We had the vet check her but there was nothing really wrong. We kept her warm and offered her all the nourishment she wanted. We watched and waited.

She left us late one morning on a grey February day as a result of a heart attack. The other horses hung closely around her but they knew her spirit was gone. And with it went a beautiful, loving, equine friend. Since then, we have experienced the sadness of loss a number of times as other horses and ponies have left our world either due to tragic illness or complications from advanced age. In the emotional trauma of loss was the stress of deciding how to dispose of the body.

Everyone who has owned horses over a period of time has had to face that awful, poignant moment when they have to say goodbye. With the death of a horse comes the immediate need to dispose of the horse’s body. But planning ahead for these kinds of events, or at least having an idea of what is the most preferred method, makes the final closure to these sad situations easier.

The carcass of a large livestock animal contains a great deal of organic matter. A typical fresh carcass contains 32 percent dry matter of which approximately 52 percent is protein, 41 percent is fat, and six percent is ash, depending on the species. Improper disposal of an animal poses various environmental consequences. For most horse owners there are several ways to dispose of a large livestock carcass: burial, incineration (or cremation), removal by a trucking service for disposal at a municipal site, rendering, or natural disposal.

Saying goodbye to an equine companion is difficult, but keeping a memento, such as a lock of mane or tail, can help preserve the memories of happier days. The stress of this difficult time can be minimized by planning ahead for your horse’s final resting place.

Burial

Burial on the farm must meet various provincial environmental guidelines depending on where one lives. While burial may be a suitable practice in summer, it is more difficult and problematic in winter due to frozen ground and winter conditions. The primary environment concerns related to dead animal disposal through burial on a farm are:

- Death due to disease that results in the spread of that disease to other livestock;

- Burial sites that could result in water pollution (both surface and ground water sources) or air pollution;

- Concentration of flies or rodents that results in the transfer of disease to people, livestock, or wildlife;

- Foul odours from decomposition of the organic matter that can be offensive to neighbouring residents;

- Attraction of predators or scavengers (bears, coyotes, wolves, birds of prey) to the burial or holding site that may endanger people, other livestock, or wildlife or spread disease. (Under the Canada Wildlife Act, it is an offence to feed dangerous wildlife).

Under the laws of British Columbia, no burial or holding site must cause or allow anything that could result in contamination of the domestic water system. Section 7(4) of the Range Practices Regulations requires that dead livestock within 100 metres of a watercourse in a community watershed be removed within 24 hours. Under the Sanitary Regulations of the Health Act, Section 9 prohibits any accumulation or discharge of any wastes that could threaten public health. Any livestock cemetery or holding ground must be separated from any and all wells by at least 122 metres.

Under Alberta’s Destruction and Disposal of Dead Animals Regulation, farmers with any type of domestic animal including poultry must dispose of mortalities within 48 hours of death. Contamination of ground water will depend on the soil group, soil type, and the groundwater depth. Coarse soils may increase groundwater contamination since they allow liquids to move quickly through the layers of soil to underground water sources. The best soil condition to reduce contamination is a fine-grained heavy soil, like clay, that slows absorption. But on the downside, it contributes to run-off that in turn threatens surface water sources. Alberta’s Environmental Farm Plan includes methods for determining the potential for groundwater contamination on a farm and more information can be obtained from their booklet “Livestock Mortality Burial Techniques” available at their website www1.agric.gov.ab.ca. Similarly, the BC Ministry of Agriculture and Lands has a Waste Management Fact Sheet for large animal disposal which is available through at www.agf.gov.bc.ca/resmgmt/publist/300Series/384300-3.pdf.

In Ontario, the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs and the Ministry of the Environment have developed new regulations for the disposal of deadstock. The Dead Animal Disposal Act (1968) was replaced in March 2009 by the Disposal of Dead Farm Animals regulation under the Nutrient Management Act and the Disposal of Deadstock regulation under the Food Safety and Quality Act. The new regulations provide more disposal options for livestock producers and meat plant operators along with measures that will protect the environment. More information about the regulations can be found on their website at www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/livestock.

Removal

A haulage service that will take dead livestock for safe burial at a municipal location. Your veterinarian should know of the services available. If not, phone your local municipality.

Incineration (cremation)

Incineration, or cremation, of a carcass should be done in a regulated facility such as that operated by the BC Ministry of Agriculture and Lands in Abbotsford, BC. In past years when we have lost a horse or pony, a haulage service has taken the animal to the laboratory where it is autopsied then cremated. The autopsy results are sent to the attending vet. The ashes are not returned since the body is placed in the incinerator along with other processed livestock.

Rendering

Dead livestock are removed to an approved disposal plant where they are immediately processed into feed ingredients such as bone meal, meat meal, or liquid animal fat. While it may seem a convenient, clean, and waste-free solution for some people, the option has its limitations. According to Alberta Agriculture, the rendering company offers on-farm pick up for a fee. But some companies may be selective about which species of livestock they will accept and which geographic locations they will serve.

Since transportation is expensive, pick up may only be done when the renderer is in the area and can make several stops. This would then affect the quality and condition of the deceased animal from the moment of death to the timely pick up date. This would be especially difficult during summer when decomposition accelerates and nuisance animals and odour become an issue. Rendering may work for some but for other horse owners it could be problematic.

Natural Disposal

This is the least desirable way to dispose of a dead animal but might be acceptable for those living on large farms or ranches. Basically, the body is left in a remote, safe location away from water sources where it decomposes naturally and is eaten by scavengers. Of paramount importance is that a) the animal must not have died from an infectious disease and b) the animal must not have been euthanized with drugs or chemicals. Both scenarios are hazardous to other livestock and wildlife through transmission of pathogens by birds and scavengers, and also hazardous to humans should the decomposing carcass leach into the domestic water table. All regulations concerning the care and control of the disposal of a dead animal must be followed according to each province’s laws and regulations.

For me personally, the most satisfying method of disposal is through incineration. First, the whole animal is removed from the farm and taken to a safe facility. An autopsy is completed and the remains are cremated in an environmentally responsible way. The autopsy provides both clarity and closure. There are fees associated with hauling the body and the autopsy but they are relatively modest. They are fees I willingly pay for the peace of mind that comes from knowing that the process is speedy, safe and final.

When we had to euthanize Star, our three-year-old Thoroughbred mare, as a result of a fatal form of malabsorption syndrome, the autopsy provided information on her condition in much more detail so that we were able to learn from that awful experience and understand all the conditions we were treating her for.

When we had to euthanize our 23-year-old Thoroughbred mare, Blaze, as a result of what we believed was colic, the autopsy showed that she actually had a tumour growing on a stalk that had wrapped itself around her intestine. It was clearly a fatal condition and the appropriate decision to euthanize gave both comfort and closure.

When we had to euthanize Penny, out 32-year-old Welsh Mountain Pony, because of what we thought was a stroke, the autopsy showed that she actually had a brain tumour and an infection in her right guttural pouch. Again, euthanizing her was appropriate and humane.

And when we had to dispose of Zona’s body, we brought in an excavator operator and buried her in a deep, safe place well away from any water courses.

Remembering

In every situation when we have lost a horse, there is a small ritual we practice. It may seem silly to some but to us it is a keepsake, a memento for all the memories and happy times shared with a beloved equine. We take a snippet of mane or tail, place it in a plastic bag with pertinent information and keep it in a safe place. In the future, we may place these beneath a memorial tree.

Decades ago we had an aging and beloved Anglo-Arab mare called Lou. She belonged to my mother-in-law who adored her and Lou lived on our acreage. When she died, I kept a lock of her mane. That Christmas I had a photo of Lou enlarged and framed, then trimmed the framing with a braided piece of mane. It was a special gift for Mom. She cried for hours, remembering through touch all the shows and the travels she shared with Lou. It was a treasured gift.

While some people plant a special bush or tree in memory of a lost friend, others have taken advantage of inscribing special words on a brick or a plaque at Langley, BC’s Spirit of the Horse Memorial Garden in Campbell Valley Park. This beautiful, peaceful place is dedicated to “embracing the majesty of equus; animals who have forged the lives of many…”

There is something utterly tranquil and, yes, spiritual, in this pastoral country garden where meandering brick walls, granite benches and a special memory lane are made with plaques filled with inscriptions and personal messages, thoughts and memories, poignant words of meaning, tears, hopes, and messages of peace and love.

Finding closure when an equine friend dies means not only deciding in a responsible way the last resting place for its physical body but embracing and giving thanks for the memories shared and treasured. It is a final act of love.