By Shawn Hamilton

The Lac La Croix Indigenous pony, named after the Lac La Croix First Nation, now the Gakijiwanong Anishinaabe Nation, primarily existed in northwestern Ontario and across the United States border into Minnesota. This unique pony breed, considered to be developed by the Indigenous Peoples, was used for winter transportation, running trap lines, hauling logs and ice, and pulling sleighs. As forest dwellers, the breed boasts strong hooves to endure the rocky terrain of the Canadian Shield; fuzzy ears to protect them from insects; and often a dorsal stripe down its back and zebra stripes on its legs.

The breed was well on its way to extinction in 1977 before a “pony heist” changed its destiny. Now with no more than 200 horses in Canada, found in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia, as well as Wisconsin and Minnesota in the US, the breed is considered critically endangered but making a comeback. The Ojibwe Horse Society maintains the breed registry of the horse, which is now officially registered as the Ojibwe Horse but commonly referred to as the Spirit Horse in honour of their connection to the spiritual past and ability to heal intergenerational trauma. Although small in size, the Ojibwe Horse’s history is full

Related: Rediscovering Equestrian Sports from Long Ago

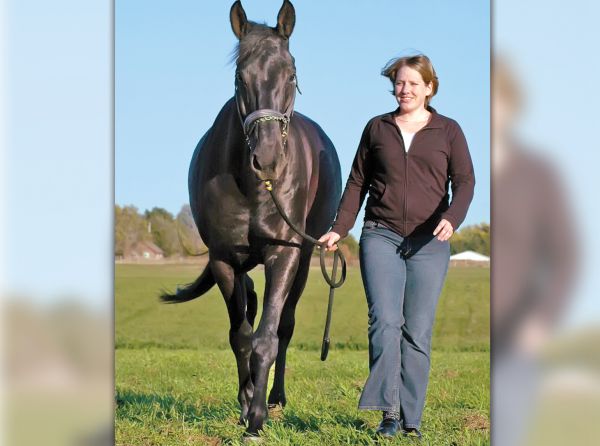

The 16-year-old mare, Wishkossiwika (Sweetgrass). Photo: Clix Photography

In the 1940s, a large herd of the Lac La Croix ponies on a reservation in Bois Forte in northern Minnesota was destroyed at the request of missionaries, who considered it inappropriate for the residential children in the area to witness horses breeding in nature. This resulted in the full extinction of the breed in the US, leaving only a small herd north of Lake Superior in the Lac La Croix First Nation region. The remaining herd in Canada was used in the winter for trapping and pulling; their work was rewarded with food, shelter, and protection from wolves and other predators. Just before the ice melted, the ponies would be herded back to an island known as Pony Island to breed, foal out, and forage on their own.

For various reasons, including the use of snowmobiles to do winter work and the last remaining breeding stallion mistakenly shot by a hunter who thought it was a moose, the herd began to dwindle. With only four mares remaining in all of North America in 1977, Canadian Health officials felt they were pests and ordered them to be destroyed. When Lac La Croix native, Fred Isham, living in Minneso ta at the time, got wind of this proposal he and his accomplices devised a plan to save the mares and ultimately the breed. With the island only accessible by air, snowmobile in winter, or boat in summer, they resorted to a rescue plan involving a Ford pickup pulling a 20-foot trailer over frozen waters, through narrow forest paths, and down snow-drifted roads to smuggle the mares back to Minnesota.

Award-winning Canadian children’s author Heather O’Connor co-wrote Runs with the Stars with Darcy Whitecrow, a caretaker of the breed, based on the return of the Ojibwe Horse. Heather shared an article with me written by John Murrell, published on February 20, 1977 in a Minnesota newspaper, titled The Last Round Up, which tells the story of the heist to bring the mares to safety with the aid of Wally Olsen, Bob Walker, Walter Saatela, and Omar Hilde, led by Fred Isham, all of whom were elderly men at the time.

With the successful return of the mares to Saatela’s farm in Minnesota, the next question was how to preserve the breed. The two older mares were 25 and 30 years old, but the younger ones at 11 years old could be bred. The decision was made to use the Spanish Mustang, Smokey SMR 169, to attempt to bring the breed back from imminent extinction.

Related: Horses' Historical Hoofprints

Migzi (Eagle), a four-year-old stallion, is an outstanding example of the Ojibwe breed. These sturdy, resilient horses stand 12 to 14.2 hands high and are known for being gentle and intelligent. Photo: Clix Photography

Mather-Simard first heard about the Ojibwe Horse through an artist by the name of Rhonda Snow, whose art appeared in the National Arts Centres The Spirit Horse Returns production that celebrated the legend of the Ojibwe Horse with a live orchestra and traditional native music.

Ayaabe (Young Buck), the weanling son of Migzi.

Assema, a yearling colt by Migzi out of Sweetgrass.

Mukaday-Wagoosh (Black Fox), an eight-year-old Ojibwe gelding.

Gwiingwiishi (Grey Jay), a six-year-old Ojibwe gelding. Photos: Clix Photography

Mather-Simard was running an Indigenous cultural centre on Victoria Island, located on the Ottawa River between Ottawa and Quebec, but after visiting the Ojibwe Horse herd at TJ stables, run by Terry Jenkins, she felt the rich history of the breed should be incorporated into her educational program. Needing more land to do this, she eventually secured a grant through The Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario to acquire a 25-year lease on a 164-acre farm, formerly Lonestar Ranch, in Ottawa’s Greenbelt region. Aptly named Mādahòkì, meaning “share the land,” the farm is dedicated to Indigenous experiences allowing people to participate and learn about the culture. Hosting the annual Summer Solstice Indigenous Festival, welcoming school groups, corporations, and the general public to experience native food, dance, art, and the horses, they have received well over 20,000 visitors to date.

In 2021, Mather-Simard purchased four geldings from TJ stables.

Related: How Horses Shaped Canada

The Mādahòkì Indigenous Ceremonial Dancers perform in celebration of the heart and spirit of Indigenous culture. Clockwise from left: Isabelle, Tristan, Charmaine, and Stephanie. Photo: Clix Photography

“They were very protective of the breed at the time, and in order to keep the bloodlines pure [they] would not sell any of the mares,” she says.

Two and a half years ago they purchased the mare Wishkossiwika (Sweetgrass) from TJ stables. She came to them already in foal with Cedar, who was the first Ojibwe Spirit Horse born on the property.

Related: Ya Ha Tinda, The Canadian Government’s Only Working Horse Ranch

Dancer Charmaine wearing a red jingle dress, with Makwa. Photo: Clix Photography

Securing two stud colts of the breed, they chose the one with the stronger genetic makeup MIGZI (Eagle) to be their stud and he is now four years old and ready to grow the herd.

Originally being forest dwellers, the native ponies are not used to grazing on rich grass so are easily prone to founder. Mather-Simard tells me that they cannot be turned out just to graze and are fed very grassy hay with no alfalfa using hay nets.

Mather-Simard’s goal is to play a small part in the support of the healthy revival of the breed and the reconnection to the Ojibwe Horse to the community.

Related: Painted Warriors - Horse Programs from an Indigenous Perspective

Stephanie performs traditional dancing, including hoop dancing. The Indigenous Hoop Dance is a dynamic and storytelling dance that uses multiple hoops to create intricate shapes representing animals, nature, and the interconnectedness of life. Performed with agility and precision, the dance is often accompanied by drumming and singing, reflecting themes of unity, healing, and tradition. Photos: Clix Photography

“They are sacred animals, smart ponies, and are willing to please, making them versatile for various activities. Their gentleness and spirit make them perfect for equine assisted therapy,” she explains.

I am honoured to have learned about the history of these small but sturdy ponies. I now better understand their representation of the resilience of Indigenous communities, and their connection with nature as a reciprocal partnership.

Related: Ojibwe Spirit Horses

Tristan performs the Indigenous Grass Dance, a vibrant and energetic Powwow dance rooted in Plains traditions, characterized by fluid, sweeping movements that mimic the bending and swaying of grass. Dancers wear long, flowing fringes that represent prairie grass, and their steps, often linked to spiritual and warrior traditions, symbolize the preparation of sacred ground. Photos: Clix Photography

For more information visit:

Related: Bareback Riding Lessons in Alberta’s Foothills at Eagle Feather Riding

Related: Canada’s Wild Horses - An Uncertain Future

My Jingle Dress

By Belle (Isabelle) Bailey

I’m from Pikwàkanagàn First Nation but reside in Ottawa where I attend school and work. I’m currently attending Carleton University, pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in Indigenous Studies. I’ve been with Mādahòkì Farm since April 2024 as a Cultural Ambassador. I enjoy beading, teaching cultural workshops, and dancing at Powwows.

The style I dance is called the Jingle Dress. The story comes from a young girl named Maggie White who was very ill. Her grandfather, who was worried about her, had dreams and visions about a beautiful dress that would heal her. With the community and her family’s help they created this dress for Maggie. At first, she was too sick to dance, so they carried her. But by the end of the song, she was able to dance all by herself. The dress had cured her of her illness.

Photo: Clix Photography

My dress is inspired by the Every Child Matters movement. It is a dedication not only to my family but to other Indigenous families and communities. The white jingles on my dress represent the children taken away to residential schools. I chose the colour white because it represents purity and innocence. The symbol I have on my dress and all my beadwork is the tipi in sunset colours. When I dance, I’m calling on the spirits of Indigenous children to go into the sunset home to the tipi where they feel safe, loved, and where they belong.

Related: Equine Assisted Learning: Changing Lives Through Horses

Related: Bear Valley Rescue

Main photo: Dancer Isabelle wearing an orange jingle dress, with Makwa. Photo: Clix Photography