By Margaret Evans

Life for a 19th century cowboy was a steady routine of guarding cattle, moving them to grazing ranges, and driving them to market, often on long and difficult trails. But in those open range days, cattle belonging to one outfit would mingle and graze with cattle from other outfits. Twice a year in spring and fall, ranchers joined in a round-up of hundreds of cattle to sort out the different brands and reclaim their herds.

Each outfit had a sizable remuda, or herd of horses, and each cowboy had his own string of horses that he would use for one purpose or another. One horse might be ideal for night patrol, another would be used to ride herd and keep the stragglers and wandering cattle contained, while another might be used for roping.

But among a cowboy’s string of horses was one that seemed to have cows figured out better than most. It was his cutting horse — the mount he used to separate a single cow from the herd and keep it apart. With pricked ears, a focused eye, strength, and nimble feet, the horse would have a unique sensitivity to anticipate every move the cow made. It would be able to quietly enter the herd to separate a particular animal without causing anxiety among the others. It would have “cow sense,” seeming to anticipate the cow’s every move, and possess the persistence to get the job done.

For the cowboy, a skilled cutting horse made the job easier, safer, and more efficient. They knew too well that one spooked cow could start a life-threatening stampede. A dependable cutting horse was valuable on so many levels. The horse was not only fun to ride, but inspired riders to compare one horse against another in a display of showmanship and, almost by default, launched the sport of cutting.

The very first advertised cutting horse competition was held in July 1898 at the Cowboy Reunion in Haskell, Texas, a small town some 80 kilometres north of Abilene. Haskell was originally called Willow Pond Springs when it was founded in 1885, but renamed after Texas Revolutionary War hero Charles Ready Haskell.

According to the National Cutting Horse Association website, the Cowboy Reunion received wide publicity from both the Dallas News and the Kansas City Star. This was a unique event and the cutting competition offered $150 prize money, a huge purse in those days. Thousands of people rode to the venue from miles away. Among them was Sam Graves who brought his 22-year-old cutting horse Old Hub out of retirement, filled him with oat mash and hay, then led him on a two-day journey to Haskell, quietly confident of Old Hub’s cutting skills.

In total, 11 competitors entered but Graves and Old Hub won the purse. The horse went back into retirement and Sam Graves knew that he had enough money to provide for his horse in his final days. Today, the Sam Graves Memorial Cutting is held annually at the Wild Horse Prairie Days Ranch Rodeo in Haskell.

The first record of a cutting horse exhibition was held in 1919 at the Southwestern Exposition and Fat Stock Show in Fort Worth, Texas, then added to the annual rodeo as a competitive event the following year. Over the next two decades, cutting became so popular that a group of horse owners decided to form an association to set rules and procedures. In 1946, the National Cutting Horse Association was formed and, in the fall, the first show was held in Dublin, Texas.

Cayley Wilson riding Right Again, owned by Nancy Wells. Photo: Janice Reiter Photography

Cutting was equally popular in Canada, so much so that, in the fall of 1949, 25 ranchers and men associated with the cattle industry met in High River, Alberta to explore ideas to put together cutting contests. That meeting led to the formation of the Canadian Cutting Horse Association in 1954. Early contests were held with ranch horses of all breeds and shapes — Quarter Horses, Appaloosas, Arabs — and others of unknown origin. In a collection of historical notes compiled by Denny Mighall, secretary-treasurer for CCHA in its formative years, he wrote that the Quarter Horses were nearly all of the “bulldog” type, stocky with heavy quarters and stout, rough legs.

“At times it was difficult to line up five horses to enter, due to the fact that they, and the riders, were otherwise employed back home at the ranch,” writes Mighall. “Transportation was an uncertain affair over miles of dirt roads in a variety of contraptions which passed for horse trailers, which would be regarded today as unfit to haul goats in. Trailers of every type and size were in evidence, all homemade, and equipped with hitches which were the brainchild of the owners. Brakes and lights were not yet fashionable.”

If the 1950s launched the sport of cutting in Canada, the 1960s saw it explode across the country. In British Columbia, Charles “Chunky” Woodward, long-time owner of the Douglas Lake Cattle Company in Merritt and grandson of Charles Woodward who founded the department store chain, was instrumental in promoting the sport with his world champion Quarter Horses Peppy San and Stardust Desire.

In 1963, Woodward purchased Peppy San as a four-year-old from Texas breeder Gordon Howell. He was the 1967 NCHA World Champion cutting horse, inducted into the American Quarter Horse Hall of Fame, and became the foundation sire for Douglas Lake Ranch’s equine breeding program. He had been trained by Matlock Rose of Gainesville, Texas, who also guided the mare Stardust Desire to world champion status in 1966. Woodward bred the mare and other quality Quarter Horse mares on the ranch to Peppy San, producing a line of world and Canadian national champion cutting horses.

Related: The American Quarter Horse

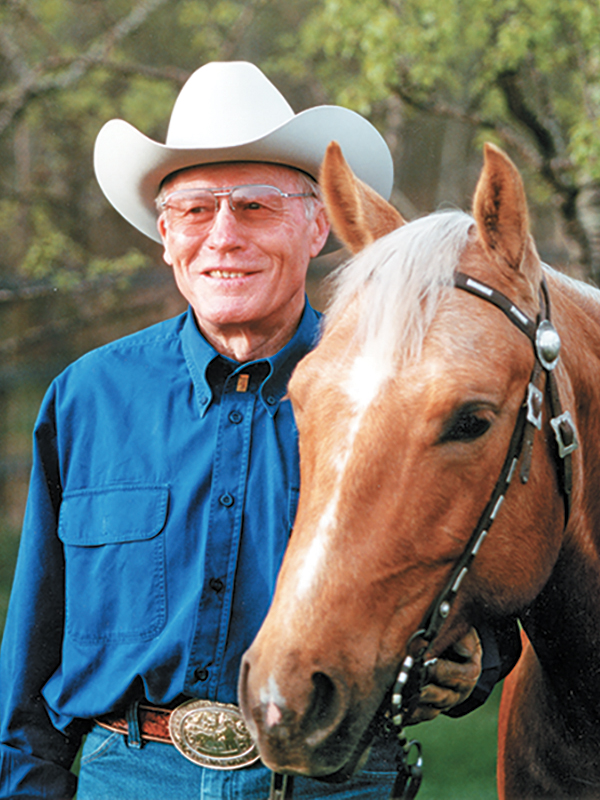

Among Canada’s legendary cutting horse trainers was Bill Collins. Born in Alberta in 1924 to a ranching family, Collins grew up surrounded by rodeo and focused on cutting in 1956, eventually offering clinics across Canada, England, and Australia.

In 1962, when Woodward hosted HRH Prince Philip at the Douglas Lake Ranch and entertained him with a demonstration of cutting, Collins gave the Prince instruction in Western riding and cutting. The Prince was so taken with the sport that he floated the idea that cutting would be a great attraction at horse shows in England. That one-liner led to a three-month tour of England in 1964 when Canada’s top Quarter Horses and riders, including Collins, showcased their skills to British crowds totaling a million people. Collins won the Canadian Cutting Horse Futurity in 1967, 1972, and 1983, and, in 1974, he won the Canadian Novice & Open Championships on Peponita, a son of Peppy San.

Bill Collins is one of Canada’s legendary horsemen. He has helped develop the sport of cutting in Canada and worldwide, has been a top rodeo competitor, and has mentored and taught thousands of Canadian youth. Photo courtesy of the NCHA

In 1964, Bill Collins and other top Canadian cutters, along with six cutting horses, spent three months in England demonstrating their skills to appreciative British crowds. Collins is demonstrating bridleless cutting.

In the late 1950s, cutting horses were brought to Ontario. Competitors Roy Ionson with his mare, Gypsy Maid, and Dale Purdy riding his palomino gelding, Pale Pete, showcased the skills of Quarter Horses at the first cutting exhibition at a three-day horse show near St. Catharines. The popularity of the event led to the incorporation of the Ontario Cutting Horse Association in 1973, the same year the British Columbia Cutting Horse Association was incorporated.

But what, exactly, is cutting?

While cutting can be defined as separating a cow from its herd, the sport is so much more than that and calls into play precision, anticipation, strategy, and a horse’s innate cow sense.

According to the Canadian Cutting Horse Association Rule Book, a rider has two and a half minutes to separate, or cut, two or three cows from a herd. The rider must select one cow from deep inside the herd, which is usually a minimum of 30 cows, and can choose to select another cow from the edges or outer regions of the herd. He is assisted by two turn-back riders who turn the cow back to the contestant if it escapes to the far end of the arena. The other two are herd holders who contain the herd and allow the competitor ample opportunity to enter the herd, cut a cow, and set it up in isolation in the middle of the pen.

A rider starts his or her run (performance) with the bridle reins in one hand and the other hand up. Once the rider has separated the cow from the herd, it becomes the job of the horse to keep it isolated. This is the time when the horse runs to block the cow, drops low, and pivots to prevent it from rejoining. When the horse is given control of the cow, the rider drops his free hand onto the horn of the saddle. Once down, the hand cannot be moved. The horse now has its head and is free to make its moves. During this phase, the rider can only give guidance to the horse with his feet.

The quality of the run depends on how well the horse independently controls the cow and prevents it from returning to the herd. A good cow is intelligent, alert, and sharp, and a great cutting horse is one that can anticipate and block its every move until the cow stops and the rider takes his hand off the horn, or “tags off.”

“You are judged on herd work, the way you cut a cow, the way you drive a cow out, move it away from the herd,” says trainer and competitor Travis Rempel of Langley, BC. “A big part of it is the herd work. Once your hand is down [on the horn], then it’s how your horse controls the cow. Does your horse have lots of stop, eye appeal, does it intercept that cow before it goes to the wall and keep the cow in the middle of the pen? Does the rider create a pretty picture? The rest of the points on the score card play into showmanship, courage, and time worked. Did that person work that cow for a while or just a couple of moves and get off of it? Did they show the judge they wanted to win? It’s the factors of the horse and the rider together that create a run. There are a lot of great horses, but if you don’t cut a cow in the right spot in the right way, that horse won’t be set up to work that cow to the best of its ability. Any great horse needs to be piloted well.”

Travis Rempel riding RPL Smart Ruby Rey, owned by Kathi Fisher, in the Bonanza Cutting Show Open Division at Circle Creek Ranch, Kamloops, BC. The horse is owned by Kathi Fisher. Photo: Janice Reiter Photography

The way the competition is scored is that the rider starts with 70 points and, depending on how the horse and rider perform the task, the score can drop to 60 or increase to 80 points. The highest score wins. In the bigger shows there may be more judges to a maximum of five. In this case, the highest and lowest scores are set aside and the remaining three are added for a final score.

A number of breeds have been trained to compete in cutting, but those that excel are almost exclusively Quarter Horses, especially at the higher levels.

“The modern-day cutting horse has a disposition and mind that is very easy to train,” says Dr. Denton Moffat, equine veterinarian in Armstrong, BC, cutting horse trainer, and NCHA Hall of Fame rider. “I always compare a cutting horse to a gymnast in the human field. They are very athletic, agile, and strong. As an open [level] cutting horse, the Quarter Horse is the only breed that excels. There are some Arabs and Morgans that have competed, but today we hardly see any other breeds because they are not competitive enough.”

Related: The Importance of Bloodlines When Choosing Your Western Performance Partner

Denton Moffat riding Kit Kat Maisie owned by Dale and Marilyn Henry, in the Four-Year-Old Open, Bonanza Cutting Show at Circle Creek Ranch, Kamloops, BC. Photo: Janice Reiter Photography

Trainer and competitor Brent Stewart of Langley, BC agrees.

“Quarter Horses are more suited to the work, and genetics play a big part,” he says. “The horses need to have conscious thought to be able to be a cutting horse. [Over the years] the horse has been the main change. The level of horses and genetics now is amazing. They work totally different than they did a decade ago.”

Horses bred for cutting have an innate sense of a cow’s behaviour. That “cowiness” became a defining trait as breeders produced more superior cutters. The Quarter Horse proved that it could take the pressure, was level-headed, knew its job, and wanted to win.

“I had one mare and used to show her years ago,” says competitor Doug Wiens of Chilliwack, BC. “She was quite a producer. Her babies have won over $400,000. I got out of breeding but a couple of years ago I bred another mare and raised her filly. I recently sold her to a buyer in Saskatchewan. I’ve got a four-year-old and we’re hoping she will be a good broodmare down the road. See how she performs.”

Doug Wiens riding This Cats Max in the Non-Pro at the Heritage Classic, Chilliwack, BC. Photo: Janice Reiter Photography

As quality horses enter the sport, they raise the expectations and performance of the riders.

“As in any equestrian discipline, horses and competitors continue to raise the bar and redefine our version of excellence,” says competitor Lois Clough of Aldergrove, BC. “Today’s cutters are bred for one single purpose and the movement, cowiness, athleticism just continue to get better and better as breeders hone the DNA. The cutting horse bloodlines are just bred and born to do that job, and with the right training most excel. Trainers and riders seek out the bloodlines that have been proven in that discipline.”

She says that cattle are, by nature, not only herd animals but have a tendency to spook. Their first reaction is to move away from the horse and try to return to the herd. The skill of the horse is to block that return. It is that interaction between the two species that is the basis of the competition.

“A horse that is quiet around the cattle, reads a cow well, and can anticipate its every move is mandatory,” she says. “When a horse is working a cow, matches its movements, and shuts off its escape at every turn, you will usually see the cow give in either by standing still or turning away. In the middle of a run this is when we say that the cow has released you and you can quit that cow and go get another. Some horses just mentally and physically defeat a cow quicker than others.”

The unique part of cutting, unlike most other equestrian sports, is that there are three independent species involved – humans, horses, and cows. As the rider lets the horse control the cow, Clough says it’s similar to two racehorses running neck and neck on the final stretch.

“These animals are communicating with each other even though it is not visible to us,” she says. “It’s not unlike two racehorses matching stride for stride and one often just has the look and the demeanour that causes the other to throw in the towel. It’s the look in the eyes.”

Kaylen Eek riding Little Fashionista, owned by Meaghan Huffman, in the $1,000 Novice Horse Open at a BC Ranch Cutting Horse Association show. Photo: Janice Reiter Photography

Brent Stewart riding Cattin Dually, owned by Rob Kuiper, in the $25,000 Novice Horse at Highland Valley, Logan Lake, BC. Photo: Janice Reiter Photography

Training horses and learning the skills of the sport mean having access to cows. Depending on where you live, that can be a big challenge.

“It varies geographically,” says Rempel. “On the west coast, we virtually never get a chance to train on a big herd and the herd work is one of the biggest challenges. In Canada, we tend to cut a lot of Black Angus or Charolais. In the US, they work a lot of Brahmans or Brahman crosses. The best cattle down south are the long-eared cattle.”

He says that, while some competition herds are a minimum of 30 head, herds elsewhere such as at competitions in Calgary are 60 head or more. That might sound more challenging, but a large herd is easier for the line-up of competitors, especially when larger shows call for three cows to be cut per competitor. A large herd provides more fresh cattle. By “fresh,” Rempel means cows in the herd that have not been cut, or worked, by another competitor.

“Our big thing is that we want to cut fresh cattle, ones that have not already been cut in the competition,” he says. “Sometimes in the bigger shows with a bigger herd they will put four head per cutter, so there would be lots of fresh cows to go around, lots of options. With those bigger bunches it’s easier to get better cows and [therefore give] a better show.”

Related: Top 5 Myths About Cutting Horses

The challenge of accessing cattle for training has been offset to some degree by the use of a mechanical cow. Often referred to as a flag, it is a calf-size stuffed cow, or a ball, mounted on a set of cables and it moves back and forth to simulate a cow’s movements. It is run by a control box and some systems allow the rider to have a remote controller attached to the wrist.

“The mechanical cow is extensively used in every training barn and many cutting trainers will have one in their own arena,” says Clough. “This tool simulates a cow and can be run with a remote control. Much of the training of a horse and rider new to cutting can be done on the flag. It’s also a great introduction to cutting for beginners, as the speed and direction can be controlled by the operator and riders get to learn in a very managed situation. Cattle by nature can be erratic, and cutting horses are quick on their feet when working them. Learning on a flag removes that element.”

Like many equestrian sports, cutting associations see their membership numbers fluctuate up and down. There may be many reasons and the local/regional economy is one of them. While some provincial associations are holding their own, the national association is seeing a marginal increase.

“Our number of cuts was up this past year with 200 extra cuts,” says Les Jack, president of the Canadian Cutting Horse Association. “Our membership is slightly up by about four percent, so we had some growth. We have worked really hard at the Canadian level with our affiliates to promote the sport, but people only have so much disposable income. But if you really like something, you’ll find a way. Our membership is not a young membership. We have people who are, on average, about 50 to 55. Many are middle-aged.”

British Columbia is mirroring that growth after a slump in activity in recent years. In 2018, the BCCHA cancelled three of their regular shows in the Interior due to lack of support. 2019 saw a revival with the launch of the Heritage Classic in Chilliwack, however was postponed from 2020 onward due to the restrictions in place during the COVID-19 pandemic. Returning with a 2022 show series, more info can be found at the Heritage Classic website.

“In British Columbia the sport is experiencing an exciting comeback, especially in the Fraser Valley,” says Clough. “Cutting’s heyday was in the 1970s and 1980s when competitions were held at the PNE [Pacific National Exhibition], Thunderbird Show Park, and Cloverdale Rodeo. But the epicentre for cutting moved to the Interior of BC where large herds of cattle were more plentiful and more easily accessed for training and hosting shows.”

Debbie Hall riding Sanjo Royal in the annual Bridleless class at a BC Ranch Cutting Horse Association show. Every year this class raises money for Canuck Place Children's Hospice in Vancouver, BC.

Similar challenges exist in Ontario. Katherine VanBoekel, a director with the Ontario Cutting Horse Association, raises cutting horses and works with a trainer in Texas. She and her husband compete at the amateur and non-pro level, and travel frequently to the southern States for competitions.

“In Ontario, of the cattle available, we can only access cattle that are a little larger than what we prefer,” she says. “But the competition has improved, the riders are better, and the horses are much more athletic. It makes the sport more challenging and more focused. It keeps you looking for that equine athlete that is better than the last one.”

If access to cattle is a problem in some regions of the country, access to a trainer is a challenge in other regions.

“We have some very good trainers in Saskatchewan, but we only have a few so most people have to travel some distance to get coaching and the quality practice they need to be competitive,” says Kim Brady, president of the Saskatchewan Cutting Horse Association. “We try and focus on the youth cutters and make it as much fun and as affordable for the parents as possible. It’s amazing how fast youth riders can learn and pick up the sport. For them, they don’t need to have the best cutting horse. [They just need] an older, honest horse that will look after them in the show pen.”

Moffat points out that helping new riders in our digitally connected times are quality online videos and online information that anyone can access.

“There are more clinics and online information available for learning. Access to cattle is always a challenge, but almost anywhere in the cutting community you can meet people and develop a report with those cattlemen.”

Going forward, the cutting associations offer incentives to attract new riders and build membership.

“They will have a buckle class and it’s for a new person who wants to get into cutting,” says Wiens. “They will compete in a class with riders who have never won a belt buckle. There was a gentleman by the name of Dave Robson who donated a lot of his time to cutting in Canada. He passed away and he left some funds set aside for the CCHA to develop the sport. We created the CCHA Dave Robson Novice Rider Class. The trophies are provided to each affiliate and awarded to a novice in a beginning cutting class.”

Like all sports, the costs that come with it and the time it demands can test anyone.

“Cutting comes with specific challenges,” says Moffat. “It’s a very time-consuming sport and to be competitive you have to practice a lot, which means a lot of time in the saddle. You need time, money, and skill. A person has to be an advanced horseman to be competitive.”

While mature, senior, and young riders all enjoy cutting, each is drawn to the sport for many different and sometimes life-enhancing reasons. Rempel has many clients who are business owners who love cutting because of the statistics.

“It’s like getting into a football league,” he says. “Men really love cutting because it’s so statistical. We track all earnings; we track all the horses’ earnings. We base a lot of what a horse is worth on how much it has won. Customers say they have a really good mare that’s won over $50,000 — so should they breed her? It’s like horse racing except, unlike horse racing, the owners get to ride their own horses. I’ve had RCMP officers; I’ve had all kinds of business owners who are challenging themselves. They have an A-type driven personality, are in their 40s, and have never ridden before — now they want to cut. The sport comes with precision, so it mirrors their professional world.”

Among the many reasons people come to cutting, some are deeply poignant. Rempel recalls a woman who found in cutting life-nourishing therapy. She turned to cutting after losing her son and made it to placing in the top 15 of her level. The sport gave her a focus, a goal. And peace.

Cutting has a rich heritage founded in the beginnings of agriculture, the love of horses, and the sense of accomplishment. Riders today continue to carry those values and the sport forward into a great future.

Related: Bill Collins, a Legendary Horseman

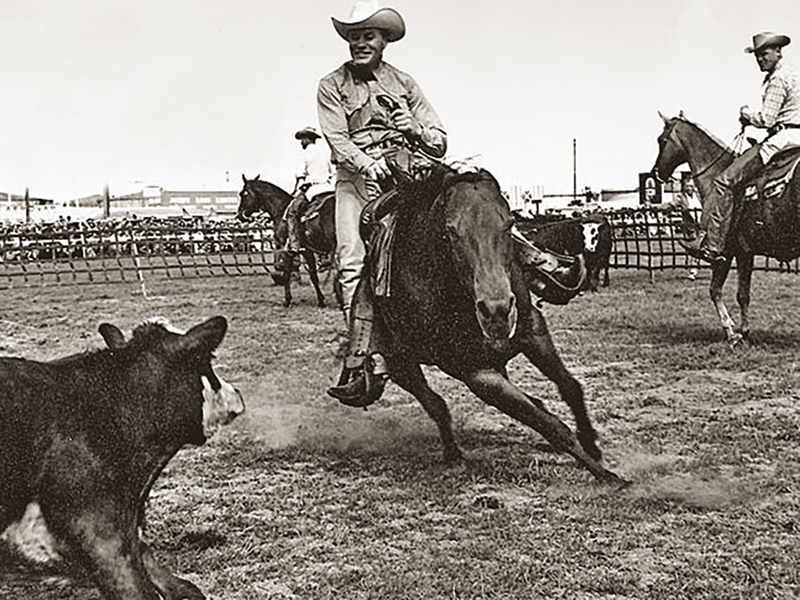

Peppy San (1959 – 1989)

Photo: BCQHA

Peppy San was bred by Gordon Howell of El Paso, Texas, and trained by Matlock Rose of Texas. He was purchased as a four-year-old by Charles “Chunky” Woodward, owner of Douglas Lake Ranch in Merritt, BC.

In the cutting world, Peppy San was a natural. In 1967, the stallion won the title of NCHA World Champion Cutting Horse and World Champion Cutting Horse Stallion, and also won the NCHA Tournament of Champions in a six go-round event in Vernal, Utah. In 1968, he went home to Douglas Lake to begin his second career as a sire of cutting horses. In December 1971, Peppy San was named to the NCHA Cutting Horse Hall of Fame.

Peppy San returned to Texas in 1975 to continue his career as a breeding stallion. Soon after, his daughter Peppy’s Desire, out of the World Champion mare Stardust Desire, was named NCHA World Champion Cutting Horse of 1975. For the first time, a NCHA World Champion Cutting Horse had sired a World Champion Cutting Horse. It was also the first time one horse dominated both NCHA divisions. Peppy San was inducted into the American Quarter Horse Hall of Fame in 1999.

In all, Peppy San sired 493 registered foals including many great cutting horses. His offspring have claimed 10 world champion titles, four NCHA world championships, and one National Reined Cow Horse Association Snaffle Bit Futurity World Championship. He also sired 1991 AQHA World Champion and Hall of Fame member Royal Santana, and five-time AQHA and NCHA Cutting World Champion Peponita, who was also inducted into the NCHA Cutting Horse Hall of Fame.

Related: The 21st Century Cowboy

Main Photo: Dustin Gonnet riding One Moore Reycy, owned by Robert Krentz, in the four-year-old open at the Heritage Classic, Chilliwack, BC. Credit: Janice Reiter Photography