By Kathy Smith

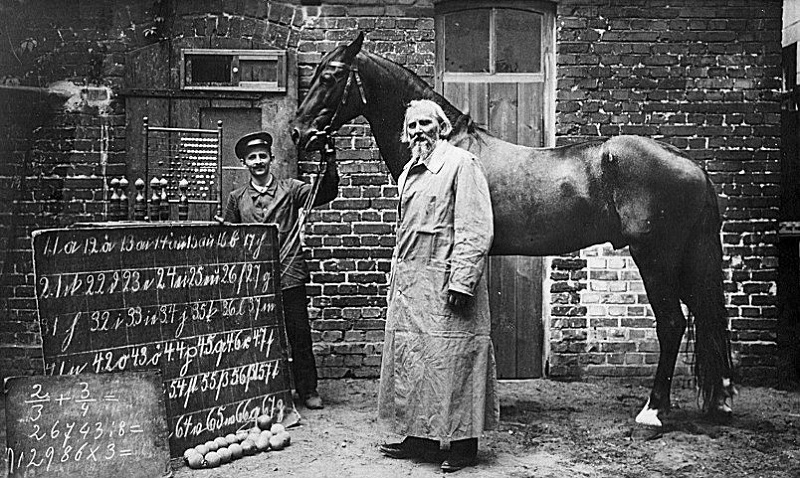

In the late 19th century, a remarkable Orlov Trotter named Clever Hans captivated the equine world with his alleged ability to perform complex intellectual tasks. Owned and trained by Wilhelm von Osten—a German mathematics teacher and part-time horse trainer—Hans was said to demonstrate extraordinary cognitive skills uncommon in horses. According to von Osten, the horse could add, subtract, multiply, divide, solve fractions, tell time, read words and numbers, spell, and even comprehend spoken and written German. When prompted with questions, Hans responded by tapping his hoof to indicate his answers.

Clever Hans became a sensation across Germany, attracting large audiences eager to witness what appeared to be unprecedented equine intelligence. Von Osten showcased the horse’s abilities in public exhibitions, notably refusing to charge admission, and in 1904, The New York Times published a feature on Hans’s remarkable performances.

Intrigued by the claims and their implications for equine training and animal cognition, the German board of education commissioned an official inquiry. Philosopher and psychologist Carl Stumpf led the investigation and assembled a panel—later called the Hans Commission—comprising 13 experts in fields including veterinary science and animal behavior. After a thorough examination, the commission found no evidence of deception or trickery in the demonstrations..

A formal investigation in 1907 by psychologist Oskar Pfungst demonstrated after many trials that the horse could get the correct answer even if von Osten did not ask the questions, and got the right answer 89 percent of the time when von Osten knew the correct answer and the horse could see him. When von Osten did not know the answers, Hans got the correct answer only six percent of the time.

Wilhelm von Osten and Clever Hans.

When the questioner’s behaviour was closely examined, it showed that he made small involuntary postural and expression changes when the horse approached the right answer. The horse was watching the reactions of his trainer and responding directly to involuntary cues in the trainer’s body language rather than actually performing the mental tasks. The trainer was completely unaware that he was providing these cues.

The Clever Hans Effect is as likely to occur in experiments with humans as with animals, and continues to be important knowledge in the “observer-expectancy effect” and animal cognition studies.

What are you saying to your horse?

Related: Your Horse's Instincts: Reactions vs. Response

Related: Use of Tools by Horses

Main image: Clever Hans performing in 1904.