A devastating demand for donkey hides is decimating the donkey population in Africa, and threatening the livelihoods of millions of the world’s poorest and most marginalized people.

By Margaret Evans

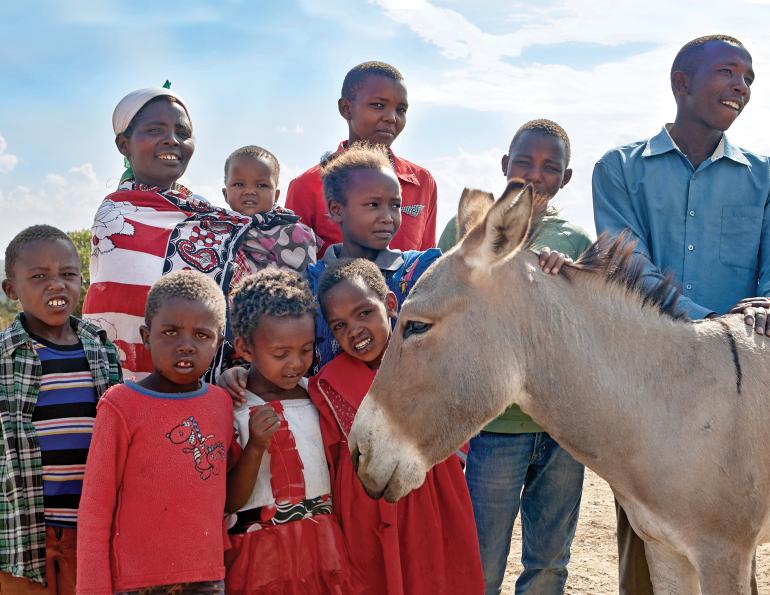

Kisima is a widow living in Nimalat, Kenya, and raises her nine children alone. She earns money through selling charcoal at the market and, to do so, she is completely dependent on her two donkeys.

“Life has not been easy,” she says. “I never wanted my kids to suffer after my husband’s death.”

Then, one night, she heard a disturbance outside her home.

“We could hear the goats’ mew, so I got out of bed. I went around the house but couldn’t see anything. I went back in because I felt it’s not good to walk by myself at night. I got up at 3 am to pray to find that only one donkey was outside.”

The other donkey had been stolen. Kisima searched extensively and the following day she went to Ntulele to look for those who were killing donkeys. After weeks of searching, she concluded that whoever took her donkey sold it somewhere else, for she never found the donkey she depended on so much.

Kisima with her donkeys. Working animals like these are essential to the livelihoods of as many as one billion of the world’s poorest and most marginalised people. As these animals are often a family’s sole means of earning a living, the loss of a donkey can be devastating. Photo: Alex McBride/Brooke

For Kisima, who was already living close to the poverty line, the theft of one of her donkeys has had a profound impact on her life and the lives of her children. Photo: Alex McBride/Brooke

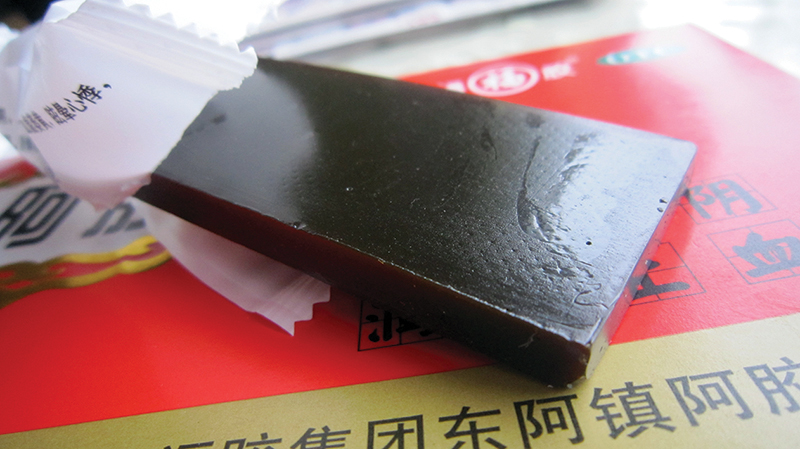

Across many countries in Africa, millions of donkeys are used by some of the world’s poorest communities. These working animals are vital for smallholder farmers and villagers to cultivate a land for planting, transport manure, bring in a harvest, take merchandise to market, and bring supplies home. The donkeys are their only means to eke out a living, so they can put food on the table and send their children to school. But donkey theft has become epidemic in Kenya and rampant in many African countries. The reason is the demand for ejiao by Chinese manufacturers. Ejiao is a gelatin found in donkey skin. The ejiao is made by boiling the skins down to a gelatinous paste, which is then used in a range of luxury serums, creams, and tablets that retail for more than $500/kilogram in China. It is also highly valued in traditional Chinese medicine.

A slab of donkey-hide gelatin called ejiao. Photo: Wiki/Deadkid dk

Above and Below: Across Africa, millions of hardworking donkeys face a grim death to satisfy the growing demand for the Chinese product called ejiao. Photos courtesy of SPANA

“The gelatin is said to contain anti-ageing properties, so is often used within face creams, but can also be used as an alternative medicine to treat blood circulation,” says Megan Sheraton with The Brooke Hospital for Animals, London, UK. “The use of ejiao in China has grown in popularity in recent years after it was rebranded to appeal to a much-increased consumer base. However, the donkey population in China has fallen dramatically in the last 20 years, meaning that suppliers of ejiao are looking to other countries for their donkeys.”

The increasing demand for donkey skins from Africa has caused market prices to rise by three or four times in some areas, making donkey ownership by people like Kisima impossible, and devastating her ability to work and put food on the table.

“One ejiao manufacturer alone has stated that it processes in excess of one million donkey skins per year,” says Dr. Ben Sturgeon, director of veterinary programs, Society for the Protection of Animals Abroad (SPANA). “With the supply of farmed donkeys in China unable to keep pace with demand (China’s donkey population has dropped from 11 million in 1992 to just 2.5 million today), producers have now turned their attention to the donkeys of Africa, and are targeting their skins on a massive scale.”

The two UK-based equine charitable organizations — The Brooke Hospital for Animals and SPANA — provide veterinary care for equines and education for owners and their families in third world countries. Both charities have been working at every level to stop the trade, theft, and slaughter of donkeys. But with the rapid growth of the Chinese middle class driving a surge in consumer demand, there is a demand for millions of donkey skins by the ejiao industry every year, putting the future of the donkey population across many countries perilously at risk.

Related: Equine Rescues, Sanctuaries, and Shelters

Sturgeon said that manufacturers make a wide range of claims, many of them dubious, about the health benefits of ejiao, such as reducing wrinkles, curing anaemia, boosting energy, enhancing libido, and even preventing cancer and shrinking tumours.

“There is scant scientific evidence to support such claims and many say it is a purely economic product,” he says. “Further analysis of content has demonstrated levels of impurity, some dangerous to human health.”

The legal status of trade in donkey skins varies in different countries where the animal product is sought.

“The trade is currently still legal in countries including Tanzania, Nigeria, and Brazil and, whilst there is currently a ban in Pakistan, there are fears that this may be lifted,” says Sheraton. “However, Kenya, which was previously described as the ‘epicentre’ of the trade, announced a ban on the commercial slaughter of donkeys in February 2020. Prior to the ban, up to 1,000 donkeys were slaughtered every day across four slaughterhouses, and some of these were illegally smuggled over the border from Ethiopia.”

But the ban on the donkey skin trade was lifted in June, just four months after being implemented. The slaughterhouses had appealed through the Kenyan courts, claiming the ban was unlawful.

“This is a huge threat to the lives of donkeys, a worry for donkey owners, and a disappointment for Brooke teams in Africa,” Sheraton says. “The situation is still very changeable. The Star Brilliant slaughterhouse in Naivasha has challenged the ban, and won a stay of operation until a hearing on 30 July 2020 at the Naivasha High Court. As well as this, the Star Brilliant, Zilza, and Goldox slaughterhouses have filed additional cases with the Nairobi High Court, which are set for mention on the 10 and 29 July 2020. However, the Kenyan government has made it very clear that they will fight to maintain the ban until donkey population numbers improve.” In August 2020, media in Kenya were reporting that the Star Brilliant slaughterhouse remains closed due to a licensing issue, and that no slaughterhouse has been licenced to operate in Kenya since the ban was instituted.

According to Sheraton, Kenya has been the most recent country to announce a ban on the trade in Africa. Prior to this, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, Senegal, and Ethiopia had all announced bans.

The crisis created by the theft of donkeys and demand for their skins is a priority for SPANA teams in the field.

“Despite bans or restrictions, many unlicensed activities remain and, with weak governance in neighboring countries, illegal movement of animals across borders is common,” says Sturgeon. “Many of these animals are either stolen or are slaughtered inhumanely at ‘bush slabs,’ with the skins being transported. This movement has been theorized to be associated with disease outbreaks and is also associated with further crime, including wildlife trade.”

He says that donkey thefts have become rampant.

“Our teams on the ground in Africa are reporting that people are almost too scared to sleep in case their donkeys are stolen and slaughtered at night. Imagine waking up one morning to find your only source of income for your family is gone. It is a truly frightening prospect for those people. In Uganda it has been reported that, due to animal loss, people have been forced into prostitution, and families have been displaced to find work.”

He says that the demand for donkey skins in China is immense. Dong’e county, in northern China, is the epicentre of production. Over 100 factories process donkey skins into gelatin every week. The 2016 demand in China was for 4.8 million skins (5,600 tonnes) and the country imported 3.5 million skins that year. With their national herd having declined 70 percent, it is no wonder they are targeting African countries to sustain demand. But that demand threatens to wipe out all donkeys in many communities across Africa within the next decade.

In Mali, one of the world’s poorest countries where 70 percent of people depend on working animals for their livelihoods, SPANA staff reported that, in 2019, 2,000 donkeys were being sold at market every week.

“At that rate, the country’s donkey population would be extinct — completely eradicated — within nine and a half years,” says Sturgeon.

The loss of a donkey is devastating and affects an entire family in many ways. A working donkey carries water, firewood, food, materials for construction, and other essential items for millions of people across Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Margaret uses her donkeys mainly for domestic chores, for collecting water, going to market, and helping on the farm. She says, “The donkey is like my entire life, it helps me in so many ways.” Photo: Alex McBride/Brooke

Donkeys have changed Stephen’s life. “Before I got these two friends of mine (the donkeys) I had no permanent job and no job security,” he says. Now he fills containers at the river and distributes the water to clients. He also augments his income using his cart, pulled by the donkeys, to help people move. “Now I wake up every day, take the donkeys to the river and get money. I have gone far and taken my children to secondary school. I have also bought my own plot so I know we will have somewhere to live.” Photo: Alex McBride/Brooke

“Children who would otherwise go to school are now obliged to help their parents with whatever loads need to be transported,” says Sheraton. “In this scenario, education goes out of the window.”

The goal is to stop the trade as a whole.

“We know that the best way to do this is to attack the supply chain,” Sheraton says. “As such, we are now setting our sights on Tanzania, where there are currently two legal slaughterhouses. The license for these slaughterhouses is now in the renewal process, and Brooke is working hard to lobby the Tanzanian government into rejecting the renewal.” However, it was reported by Brooke in July that Tanzanian authorities renewed the slaughterhouse license.

Related: Feral Donkeys & Horses Dig Wells That Benefit Others

SPANA, working with international and local non-governmental organizations (NGOs), is calling for an immediate halt to the global trade in donkey skins.

“Given growing evidence, we are calling for an immediate halt to the trade in donkey skins, which in its current form is unsustainable, compromises animal welfare, and impacts on vulnerable livelihoods and communities,” says Sturgeon. “SPANA is working with governments to put in place national bans on the export of donkey products. The trade has already been banned in many of the countries in which we work. In countries where the trade is illegal, SPANA is asking for the support of local and national authorities to enforce existing legislation and regulations.”

The challenge is that donkey theft is driven by a highly lucrative trade, and the priority is to educate owners and promote practical ways to help them prevent theft in the first place.

“We have run conferences and workshops in Mali, Botswana, and Zimbabwe where local people have had the opportunity to engage with and share their experiences with local policy and decision makers,” he says. “SPANA is also working with governments and international bodies to improve long-term protection for working animals by promoting comprehensive animal welfare legislation.”

In Zimbabwe, SPANA has been working with other local groups to prevent a major new donkey abattoir from opening. It would have slaughtered hundreds of animals a month. Those donkeys slated for the abattoir were subsequently abandoned, but the SPANA team provided feed and veterinary care, then rehomed the animals.

Both organizations have had to deal with the impact of COVID-19 in the countries where they operate.

Caleche horses in Marrakech, suffering from malnutrition following the collapse of the tourist industry due to COVID-19. Photo courtes of SPANA

Above and Below: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has created extreme challenges in some of the poorest communities, where owners are unable to feed or care for their animals due to the threat of the virus and restrictions on work and movement. Shown are SPANA veterinarians working in Ethiopia and Zimbabwe. Photos courtesy of SPANA

“The disease has spread to all of our countries of operation, with the likes of India and Pakistan perhaps worst hit,” says Sheraton. “Since March, all Brooke staff around the world have been working from home, but some of our offices have now begun to reopen in line with government regulations. However, technology has meant that we’ve still been able to provide support to vulnerable communities and their animals via phone, radio, and social media. And in countries with slightly less harsh lockdowns like Ethiopia, we’ve still been able to meet with communities at our water points and shelters, and distribute key information on the importance of hand hygiene and social distancing.”

SPANA workers have seen owners in the poorest communities unable to afford to feed or look after their animals, because of the threat of the virus and the restrictions on movement and work.

“This is threatening the survival of many working animals, which are facing severe malnutrition and other problems,” said Sturgeon. Some desperate owners, he says, “are allowing their animals to graze on the streets, but this has led to more animals eating plastic and rubbish, causing an increase in issues such as colic that require urgent veterinary attention. Abandonment by desperate owners unable to afford feed for their animals is also a serious issue. Carriage horses and animals used for rides and treks are also very hard hit in many countries, as tourism all but dried up. In Marrakech, hundreds of the city’s famous caleche horses, which transport holidaymakers around the medina, are facing malnutrition and struggling to survive.

“SPANA teams are working in very challenging circumstances, caring for animals within the permitted government guidelines. Wherever possible, our mobile clinics continue to operate and our centres remain open, particularly for emergency cases. Stringent measures and precautions are in place to protect the health of staff, owners and animals such as distancing, avoiding contact and disinfecting after each appointment.”

However, the response to appeals from both organizations has been overwhelming.

According to Sheraton, the response from Brooke’s supporters has been amazing, and reflects the fact that the distressing donkey skin trade provokes a powerful and emotional reaction from people. Brooke recently launched a petition, asking supporters to help them demand a global ban on the trade. At press time (late August 2020), the petition had just under 80,000 signatures, and the goal is 100,000.

The response from SPANA supporters and the public has also been overwhelming, and the donations have made it possible for the organization to continue tackling this devastating trade through a range of different approaches.

Kisima managed to buy another donkey but her daughter had to stay home from school for a whole term. Costs to send a girl to school include not only the school fee but uniforms and school supplies.

Today, Kisima is part of a women’s only donkey welfare group that works with Brooke East Africa’s partner, Farming Systems Kenya. Kisima’s group entered Brooke’s Linda Punda competition, a ‘Challenge’ to look for innovative ideas to protect donkeys. More than 200 donkey welfare groups were invited to submit practical, affordable, and sustainable ideas.

Winning projects included lockable shelters, solar powered security lights, guard dogs, and surveillance hubs. The expert panel included representatives from the police, vets, and Brooke partners.

“My hope is that we can build somewhere where we can shelter our donkeys and also provide someone who will guard and feed them at night and during the day,” says Kisima. “And those women whose donkeys had been taken, they should be bought new ones so that they will be able to work with us, so that we grow together.”

For more information on the work of The Brooke and SPANA contact:

To sign the petition demanding a global ban on the donkey skin trade, visit: https://action.thebrooke.org/a/donkey-skin-trade-ban

Related: Brooke USA Calls on Amazon to Ban the Sale of Ejiao

Main Photo: Kisima is raising her nine children by herself after her husband died unexpectedly. Credit: Alex McBride/Brooke