By Kentucky Equine Research

In the world of feeds and feeding, processing has become a dirty word among horsemen. The impression that any type of processing is counterproductive, detrimental, or ill-advised is a disturbing trend. Feed processing methods have been researched and developed to help horses, not harm them. What some horsemen do not realize is that even the benign practice of baling and preserving hay is a form of processing. So, what has caused this pessimism?

Understanding the methods used to process feeds, and knowing why they are used, will make the idea of feeding processed feedstuffs more savoury.

Purpose of Processing

There is no one simple reason for processing feeds, but the one common goal is to make the feed better for either the horse or owner. Processing is performed in order to improve the digestibility of a feedstuff, to extend the shelf life of a product, or to make use of by-products of the human food industry, such as wheat middlings, soybean meal and hulls, rice bran, and beet pulp.

Some forms of processing are intended to improve the convenience of a product. For concentrates, processing enables the manufacturer to make consistent products. In turn, the products become safer, easier to chew, and more appetizing for the horse. They may also be easier for the horse owner to dish up.

|

Barley, like corn, benefits from processing with heat, as heat helps break down the large starch molecules which are not easily broken down by the natural enzymes produced in the horse’s body. |

Processed forages such as hay cubes or pellets make efficient use of limited storage space, fill in when a hay crop has failed, make it easier to carry feed when traveling, guarantee a consistent intake of nutrients, simplify ration balancing, and help the owner feed horses with problems such as poor teeth or respiratory tract disorders.

Grain and Forage Processing

Grains are processed to increase digestibility. Examples of simple processing methods are cracking and grinding, particularly of corn, which are performed to reduce the size of the particles before the horse chews them.

Other effective processing methods for oats and barley are crimping, flaking, and rolling. These techniques are designed to open the outer coat of the grain to aid in mastication. Further processing entails adding heat to these techniques to produce steam-rolled barley, steam-flaked corn, super-flaked corn, and ultimately the micronizing of any grain. This is done to improve the starch digestibility of the grain.

Sun curing and dehydrating (quick drying) of hays and beet pulp are processing methods designed to reduce the moisture content of roughages so they will not mold. Chopping forages to shorten fibre length, as with chaff, is another form of processing. Although not commonly used in horse feed manufacturing in North America, ensiling or anaerobic fermentation of forage to preserve its nutrients is also a form of processing. Haylage is an ensiled forage.

Feed Processing

Feed processing is least complex when grains are mixed and coated with molasses to create sweet feed. More elaborate processing can be done to change the entire form of a mixture of feed ingredients, as with pelleting or extruding. In these processes, the ingredients are ground to improve rate of digestion, decrease segregation and mixing problems, and facilitate pelleting or extruding.

Pelleting

Pelleted feeds have become commonplace in the horse feed industry. They provide the same balance of nutrients as sweet feeds but in a more convenient form. Manufacturers can use more cereal grain by-products in pelleted feeds.

In the pelleting process, the ingredients are ground down to the same particle size, mixed with a pellet binder, and then steam heated to 180 to 190 degrees Fahrenheit for about 20 seconds.

Next, the mash is pushed through a pellet die of the desired size, cooled, and dried to prevent mold growth.

With forage pellets, the forage is dehydrated, ground, mixed with a pellet binder, and then pressed through the die. Die sizes range from 0.31 to 1.56 centimetres (1/8 inch to 5/8 inch) or greater, depending on the purpose of the pellet.

Pelleting causes gelatinization of grain starches, making them more available for enzymatic digestion. This is particularly beneficial for pellets made with substantial amounts of ground corn. If only partial gelatinization occurs on the outside of the pellet, then the pellet will look very shiny. This is undesirable and such pellets should be rejected. Pelleting increases feed digestibility less than five percent in horses with normal teeth. However, there are other advantages to pelleting.

|

Pellets are convenient to feed and handle. The pelleting process makes grain starches more available for enzymatic digestion. Desirable pellets are long, hard, and uniform, with a dull surface. |

Because the grains are ground to the same size, there is no sorting out of fine ingredients. This makes every pellet the same and guarantees that a horse will not leave less palatable parts of a feed in the trough.

It costs more to manufacture a high quality sweet feed than a high quality pellet because of ingredient prices. Pellets can be made from wheat middlings (bran, germ, and all that is left of the wheat grain after removal of the flour) and soy hulls (skin of the soybean), which are fairly economical since they are by-products of other industries. Whole grains, particularly oats, can often be very expensive and the price fluctuates from crop to crop. Some horsemen question the effects of heat treatment on the viability of vitamins and minerals added to the pellet.

Heat normally will not affect minerals because they are inorganic. Vitamins generally come with special gel coatings to protect them from oxidation and are made to tolerate short bouts of heat. However, if the pelleting process is not done correctly and the pellets become too hot, availability of vitamins and possibly chelated minerals may decrease.

Fine ingredients are usually combined into mixing pellets and then used in sweet feeds. The mixing pellet typically contains protein sources and a vitamin and mineral premix. The mix blends better if all the ingredients are about the same size.

Manufacturers of sweet feeds once had a problem with fine ingredients sifting to the bottom of feed batches, so the mix may have been different in each bag. To combat this problem, molasses was added to sweet feeds. Molasses, with the addition of mixing pellets, has resolved all problems associated with fines.

Desirable pellets should be relatively long and hard (except for pellets used in special senior concentrates) with good colour, uniformity, a dull surface, and few to no fines. When pellets can be handled repeatedly without falling apart, they are considered durable. Durability is an important consideration when evaluating pellets.

Extruding

Extrusion is the process used to make dry cat and dog foods, and now some manufacturers of popular horse feeds use this process. Extruded nuggets are made from many of the same ingredients as pelleted feeds. First, the grains are ground and mixed with all other ingredients, and then they are cooked with moist heat at about 260 degrees Fahrenheit. More complete gelatinization of starches occurs during extrusion than during pelleting.

The extrusion occurs when the mash is exposed to cooler air, and it begins to expand and pop, much like a kernel of corn. The nuggets are dried to a moisture level of about 10 percent before being bagged.

Many of the advantages of pelleting also hold true for extruded feeds. One additional advantage is the ability to add high levels of fat. With oil in the mash and oil sprayed on the outside of the nugget, fat levels can be as high as 20 percent. Because of the high temperatures experienced during processing, preservatives are not always necessary (except with high fat nuggets), which is an added benefit. The high heat does affect vitamin levels, but because vitamin degradation is expected, manufacturers put in extra vitamins to compensate for losses.

Energetically, extruded feeds have the edge in digestibility over conventional grain, sweet feeds, and pelleted feeds. The form does slow the intake of the feed, which can be advantageous for the horse that eats its feed too quickly, but it is difficult to get a horse in need of a large quantity of feed to eat enough of an extruded ration to meet energy needs. Extruded feeds are very low in fines and dust, so they are ideal for horses with respiratory problems.

|

Extruded pellets contain many of the same ingredients as pelleted feeds, but are typically easier to digest. They are low in dust content, and can slow the intake of feed, which can be advantageous for the horse that eats too quickly. |

There is a negative aspect to extruded feeds. They are more expensive to manufacture and are bulkier than other feeds, and therefore require more storage space. Palatability can be an issue because of the unfamiliar form. Introduction of extruded feeds at an early age or very gradually can help in convincing the horse that extruded feeds can be just as tasty as other feeds.

Processed Forages

Hay

Haymaking is a way of processing forage so that it can be preserved for longer periods of time and fed when fresh forage is unavailable. Drying and baling hay is considered processing because the original product is not the same as the resulting product. When fresh forage is cut and dried, the nutrient composition changes. Protein, carbohydrates, and vitamins are irretrievably lost in the drying process. For example, if grass has a crude protein value of 22 percent (on dry matter basis), it will typically only have 12 percent crude protein after being harvested as hay. Within the first 24 hours after cutting, as much as 80 percent of the vitamin A (in the form of carotenes) can be lost. If the drying process is extended or the cutting is rained on in the field, the nutrient losses are much greater. Regardless, hay is still the number one choice of forage for horses when fresh forage is not available.

Chaff and Chopped Forage

The chaff feeding tradition is alive and well in England and Australia. Chaff is simply chopped up forage. Molasses is often added to minimize dust in chaff. Some chaff may also have oil added to increase the energy value.

Traditionally, chaff was a way to feed poor quality forage like straw in a form that was appealing to the horse. The length of the chop is anywhere from 0.625 to 2.5 centimetres (1/4 to 1 inch), depending on the area of the world where it is made. Chaff is a valuable way to add bulk to a diet without providing too many calories; it also makes busywork for the stall-bound horse. Some horsemen mix chaff into the ration to slow intake. This is a good idea for horses that chronically choke as a result of bolting their feed.

However, it may not be ideal for the average horse. In a study done at Kentucky Equine Research, it was found that when hay and feed were fed at the same time, the rate of feed passage increased, and the horse did not have adequate time to digest the grain in the small intestine.

Cubes

Another method of processing fresh forage is to compress it into cubes. The hay is dried and chopped before being pressed into a cube form with a binder to hold it together. Binders are usually natural materials such as bentonite clay, which is innocuous to horses.

In South America, bentonite is a favoured feed additive because of its mycotoxin-binding capacity. South American horsemen have also seen a beneficial effect on reproduction, which can be adversely affected by mycotoxins in feed. Cubes are convenient to measure and feed. Furthermore, there is much less waste with cubes than with conventional hay. Cubes usually contain minimal dust, so a horse afflicted with heaves may benefit from them. On the downside, it is very difficult to tell how pure the forage is in the cube and whether there are weeds or any other foreign matter present.

Using a dependable manufacturer is a good idea when selecting a brand of cube. Since the forage is partially broken down and therefore takes less chewing, a horse may clean up a meal more quickly than usual. Without eating to occupy its time, a horse may look for vices to combat boredom. This can be an even greater problem with hay pellets.

Forage Pellets

Forage pellets are also used extensively in horse feeding programs. Often, forage pellets are given to horses that have no access to pasture or hay. To make the pellets, manufacturers grind dried forage, most commonly alfalfa, to a small particle size and then make it into a pellet. The premise is to make the forage as convenient as possible so it can be packaged in 50-pound bags without the dust usually associated with conventional hay. For arid areas of the country where neither grazing nor hay are readily available, alfalfa pellets are the most common source of forage and horses thrive on them. Forage pellets can also be used in conjunction with hay to improve the overall quality of a diet or as a way to sneak more forage into the diet of a horse that eats little hay. For horses that have lost many teeth, pellets can be dampened and made into a mash or slurry.

Unsoftened hay pellets can cause choke, so care should be taken when feeding them to horses that bolt their feed.

|

Hay cubes consisting of fresh, compressed forage are convenient to feed and there is much less waste than feeding with conventional hay. They also contain minimal dust so may benefit a horse with respiratory problems. |

The quality of a forage pellet is usually consistent, and the form makes them easy to digest. The nutrient contents are required by law to be on the bag or feed tag as guaranteed analyses, so it is simple to calculate if the horse is receiving its nutritional requirements. One thing that is impossible to know about a pellet is the quality of forage before it is ground. As with cubes, buying from a reputable manufacturer is recommended.

Haylage

Many horses are fed hay that has been ensiled and marketed as haylage. Feeds for other livestock have been ensiled for decades, but this type of preservation is relatively new to the horse feed industry. The forage is sealed in airtight containers with a high moisture content and allowed to undergo fermentation. There are definite advantages to feeding a horse haylage.

Fermenting the hay retains the nutrients better than sun curing, particularly protein, carbohydrates, and many vitamins.

Moreover, the higher moisture content keeps the forage practically dust-free, making it ideal for horses with respiratory problems or horses sensitive to dusts and molds.

However, there is also a danger in feeding haylage. Because of the moist, airtight environment, the bacteria that cause botulism (Clostridium botulinum) may grow if the haylage is improperly baled or stored. Vaccinating any horse receiving haylage can prevent death by botulism. Although the botulism bacteria cannot be seen, discarding any sour-smelling, burnt-looking, or slimy silage is also recommended to avoid possible digestive disturbances in the horse.

Beet Pulp

Far from what its name implies, beet pulp is a novel source of forage for the horse. Beet pulp is a by-product of sugar production that makes an excellent addition to the horse’s diet when other forage is poor quality or a horse dislikes hay.

Once the sugar is extracted from the sugar beet only the fibrous portion remains. The fibres left after extraction of the sugar are then dehydrated for packaging and to prevent mold. This type of fibre is very digestible to the microbial population in the cecum and colon of the horse, making it an excellent fibrous energy source. There is some concern about the amount of sugar in beet pulp being a problem for the horse that is sensitive to sugar.

Actually, there is very little residual sugar after the extraction process, although some molasses may be sprayed on after dehydration to keep the dust down. The sugar effect of beet pulp on horses was investigated at Kentucky Equine Research, and any residual sugar can be removed by rinsing the beet pulp a few times before setting it up to soak.

Processed Grains

Oats

Traditionally, oats were the feed of choice for horses because of their palatability, as well as their margin of safety, due in large part to their high fibre content.

Even with as little processing as cleaning the beards off the oats, they are still a very digestible source of energy for the horse. Further processing, such as crimping, steaming, cooking, or rolling, does not increase digestibility enough to make it worth the extra cost of the processing.

|

Corn should be processed with heat in order for the horse to get the most out of the feed. Steam treatment makes corn molecules easier to digest. |

The major energy source in oats is starch. The starch found in oats is easily attacked by the amylase enzyme so that it can be digested in the small intestine, where it is energetically the most benefit to the horse. The limiting factor to the capability of a horse to digest oats is the ability to chew the oat grains. If whole oat grains are showing up in the manure (not just the hull), then it is time to evaluate the horse’s teeth. Aged horses that are losing teeth would be candidates for processed oats. The problem with processing the oats is that once the integrity of the outer wall of the grain is broken, the inside of the grain is exposed to air, which prompts the oxidation and eventual breakdown of the nutrients. If the grain is steam or heat treated, it will retain its nutrients much longer because the enzymes that cause deterioration of the grain will be denatured by the heat.

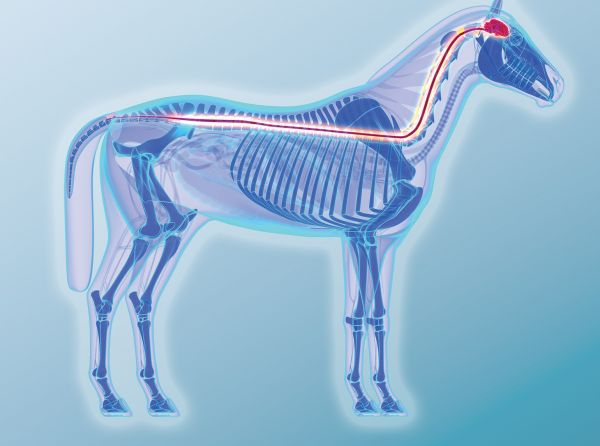

Corn and Barley

Contrary to oats, processing of corn and barley is advantageous for the horse. Corn and barley are both higher in starch than oats, but in order for the horse to get the most out of the starch in these grains, they need to be processed with heat.

Because of their large crystalline nature, the starch molecules in corn and barley are not easily broken down by the amylase enzyme. However, heating makes the starch molecule more vulnerable to amylase and subsequent digestion. In a study done at Kentucky Equine Research, different forms of corn were compared by looking at the glycemic index.

Glycemic index is a measure of small intestinal digestibility because it is an indication of the amount of sugar entering the bloodstream in the form of blood glucose over a period of time after a meal. When horses were fed cracked or ground corn, there was little difference in glycemic index, but when steam-flaked corn was fed, the glycemic indexes were significantly higher. The steam treatment made the corn molecules much easier to digest.

Why is it so important to digest grains in the small intestine instead of the large intestine? When grain escapes digestion in the small intestine and passes through to the large intestine, the microbial population ferments the starch. The by-product of starch fermentation is lactic acid, which lowers the pH of the large intestine, making it more acidic. The more acidic the environment, the unhealthier it is for the fibre-digesting microbial population. Keeping the microbial population in balance with a desirable pH is essential to the health of the horse.

Feed processing is done for the benefit of the horse and sometimes the horse owner. By improving digestibility and palatability, processing feeds can be beneficial to equine diets.

Main article photo: Robin Duncan Photography - Even the benign practice of baling and preserving hay is a form of processing. The common goal in processing feed is to make the feed better for either the horse or owner.

This article appeared in the October/November 2011 issue of Canadian Horse Journal.