By Lynne Gunville

Function follows form, according to Dr. Trisha Dowling. It’s the conformation or structure of a horse that ultimately determines its athletic function.

“A Saddlebred horse might look pretty prancing in the show ring, but it won’t be able to outrun a Thoroughbred,” says Dowling, a board-certified specialist in veterinary pharmacology and large animal internal medicine at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine.

“As veterinarians or competitors, we need to look at how a horse is built. That tells us a lot about how it will be able to do its job.”

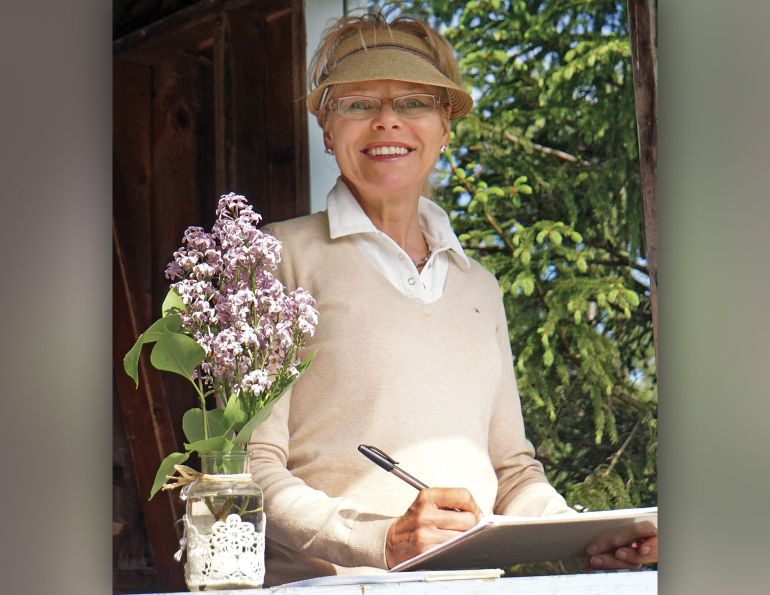

Dowling is an avid endurance rider and vaulting coach, and she uses her expertise in conformation to predict performance as well as predict the horse’s predisposition to injuries and lameness problems.

When studying the conformation of a horse, Dowling begins by checking the animal for balance. A balanced horse can be divided into equal thirds consisting of the shoulders, barrel, and hindquarters (Photo 1).

Photo: WCVM Today

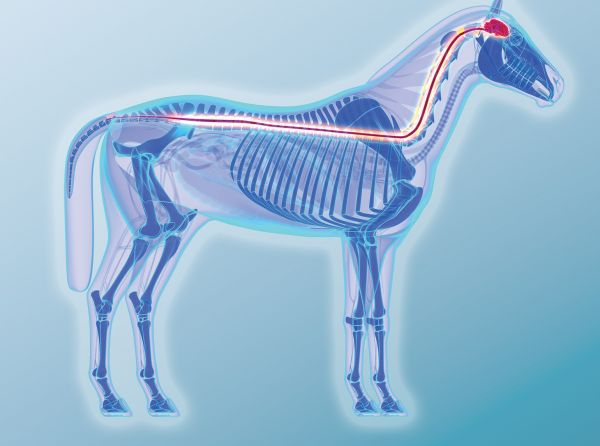

She studies the topline to determine whether the area between the withers and the point of croup is level, uphill, or downhill. Because of the weight of the head and neck, even well-balanced horses carry 60 percent of their weight on the front end, so it’s not surprising that lameness problems occur in the front legs. Horses with a downhill slope are even heavier on the front end (Photo 2). That conformational trait increases the risk of lameness and limits the potential in sports such as dressage or jumping where the horse needs to lift the front end.

Photo: WCVM Today

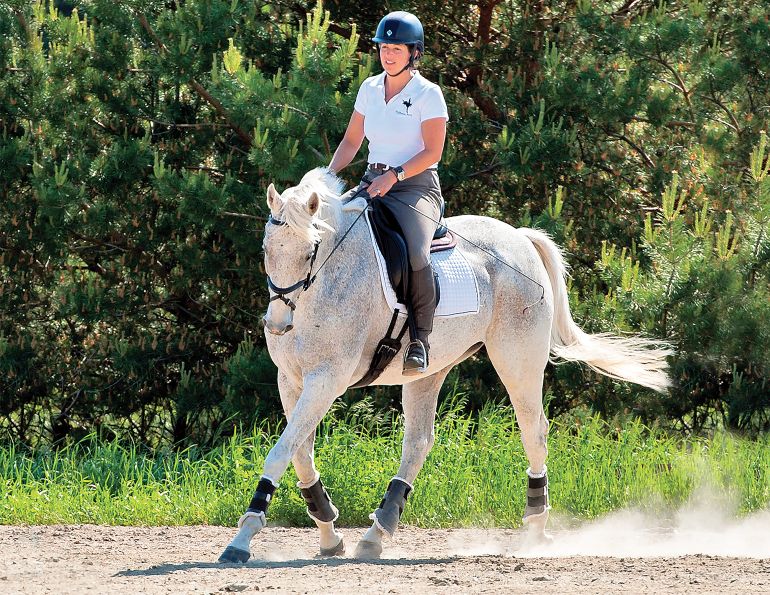

Another important consideration for Dowling is the angulation of the horse. While sloping shoulders and hips are ideal (Photo 3), it’s better to have less angulation that is equal than to have a mismatch between shoulders and hips.

Related: How Much Does Your Horse Weigh?

Photo: WCVM Today

For example, a horse with more angulation at the hip than at the shoulder will have a longer stride behind than in front and won’t be able to get its front end out of the way. With such an imbalance, the horse will either not move out well, move on a diagonal (three tracks), or wing its hind feet out around its front feet just so the animal doesn’t step on itself (Photo 4).

Photo: WCVM Today

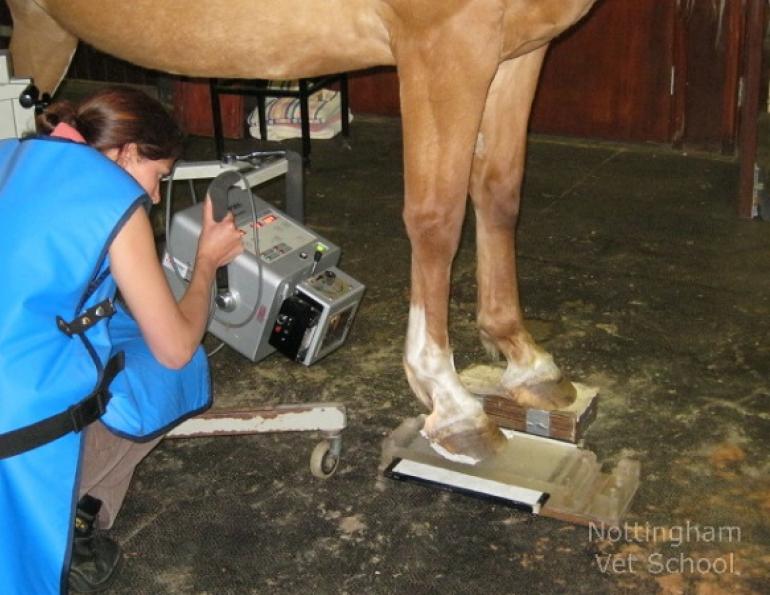

The shoulder angle is also notable since it usually matches the pastern angle – the part of the foot extending from the fetlock to the top of the hoof. An upright pastern angle results in poor shock absorption and a rough riding horse that’s prone to problems with navicular disease and other joint issues (Photo 5).

Photo: WCVM Today

A horse with calf knees has front legs that bend backwards at the carpal joints, which causes excess strain on the bones, ligaments, tendons, and joints. Calf knee is particularly serious in racehorses; as their muscles tire during a race, their legs bend even further backwards causing the little bones of the knee to be crushed by the force of impact – a condition known as chipped knees (Photo 5).

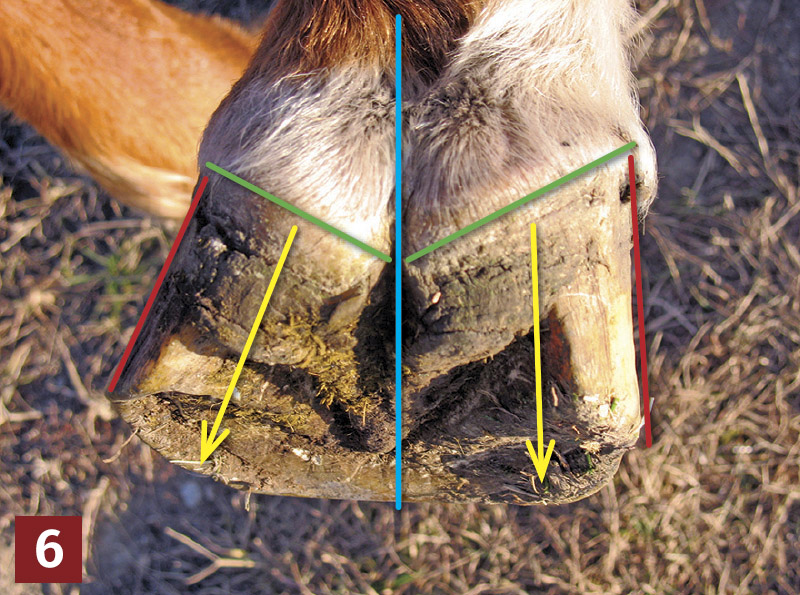

Dowling points out that it’s important to examine a horse’s legs closely to evaluate where the force of the body weight is going. This is an opportunity to anticipate future problems related to concussion. Horses that toe-in (pigeon-toed) will land with more weight on the outside of the hoof than the inside. They are prone to sheared heels, in which the hoof becomes distorted from the uneven forces travelling through the hoof on landing (Photo 6).

Photo: WCVM Today

Horses with hind legs that bow in are described as cow hocked. Because their structure places additional stress on the hocks, these horses tend to have problems with osteoarthritis, also known as bone spavin (Photo 7).

When evaluating young horses, Dowling tends to give them the benefit of the doubt with their topline because they grow faster at the hip than at the withers and often appear downhill. She also recommends that their hooves be monitored for club foot. This condition is caused by the tendons and ligaments stretching with the growth of the cannon bone so they pull the coffin bone backwards, resulting in an upright, “boxy” hoof. Club foot can be surgically corrected if it’s caught while the horse is still young (Photo 8).

Photo: WCVM Today

While all breeds can be evaluated using the same guidelines, particular breeds have structural characteristics that make them more suited to specific functions. For example, Warmblood horses are built to excel at show jumping and dressage while Thoroughbreds are built for speed.

Triple Crown racehorses like Secretariat and American Pharaoh are considered conformational marvels, but there are plenty of horses with structural imperfections that would be unsuitable for some jobs, but have just the qualities needed to shine in others. Animals with the right build for their jobs are usually easier to train and less likely to develop performance-related injuries.

Dowling emphasizes that it’s important to match the structure to the function and adds that it’s not necessarily the most attractive horse that will turn out to be best suited to his job.

“A horse might not be pretty, but with good conformation, he could perform well for you and end up lasting at his job for 20 years or more. Look at his structure, his balance, and his angles — that’s what counts. Make sure your horse has the form that’s going to give you the function you need.”

Lynne Gunville of Candle Lake, Saskatchewan, is a freelance writer and editor whose career includes 25 years of teaching English and communications to adults.

This article was originally published in the May/June 2016 issue of Canadian Horse Journal.

Main article photo: Canstock/Olgait