Update to original article posted in August 2019...

George Morris Permanently Banned

By Margaret Evans

On November 19, 2019, the U.S. Center for SafeSport listed on their website American equestrian coach, George Morris, as permanently banned for violations of the SafeSport Code as a result of sexual misconduct involving a minor. The ban against him was first reported August 5 and he was then listed as permanently ineligible (subject to appeal) by the U.S. Center for SafeSport and the United States Equestrian Federation (USEF) because of sexual misconduct involving a minor that occurred some 50 years ago. Morris appealed the ruling, but it was overturned and his bid was unsuccessful.

The U.S. Center for SafeSport is recognized by the United States Congress, the United States Olympic Committee (USOC), and the National Governing Bodies (NGBs) as the official safe sport organization for all Olympic, Paralympic, Pan American and Para Pan American sports in the United States.

Morris must now deal with the most severe sanctions placed on him by SafeSport based on the investigator’s findings of fact. He now no longer has any ability to participate in the sport at any level.

Through its investigative process, the Center for SafeSport has resolved more than 1,700 cases, found violations in 551 cases and rendered 285 people permanently ineligible to participate in sports under the US Olympic and Paralympic Committee and the National Governing Bodies’ umbrellas.

In the case of Morris, this outcome underscores the fact that no matter how long ago or how far-reaching the misconduct, the ruling is in place to protect the innocent and those who take advantage of their trust will suffer the consequences no matter their level of professional skill.

Original article here:

George Morris Receives Lifetime Ban from SafeSport

By Margaret Evans

On August 5, 2019, it was reported in all mainstream media that celebrated American coach, equestrian, and chef d’equipe for the American Olympic show jumping team had been listed as permanently ineligible (subject to appeal) by the United States Center for SafeSport and the United States Equestrian Federation (USEF) because of sexual misconduct involving a minor that occurred some 50 years ago. The knee-jerk reaction from thousands in the equestrian community was shock and dismay, and 81-year-old Morris posted his immediate response online:

“I am deeply troubled by the U.S. Center for SafeSport’s findings regarding unsubstantiated charges for events that allegedly occurred between 1968 and 1972. I contest these findings wholeheartedly and am in the process of disputing them. I have devoted my life to equestrian sport and the development of future riders, coaches and Olympians. Any allegations that suggest I have acted in ways that are harmful to any individual, the broader equestrian community, and sport that I love dearly are false and hurtful.

“I share our community’s commitment to protecting the safety and well-being of all our athletes who need reliable guidance and encouragement at every level, of which I have provided for over 50 years. I will continue, as I always have, to proudly support equestrianism and its continued development around the world.”

Morris was born in 1938 and began riding as a child in New Canaan, Connecticut. He went on to have many early successes in Horsemanship and Hunt Seat Equitation. By the time he was 21, he was representing the United States in international competition and won team gold at the 1959 Pan American Games and team silver at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome. Following his retirement from competition, he built a legendary name for himself as a coach and trainer and, as chef d’equipe, the United States show jumping team won gold at the 2008 Beijing Olympics and team gold and individual gold and silver at the 2011 Pan Am Games. He has also written six books.

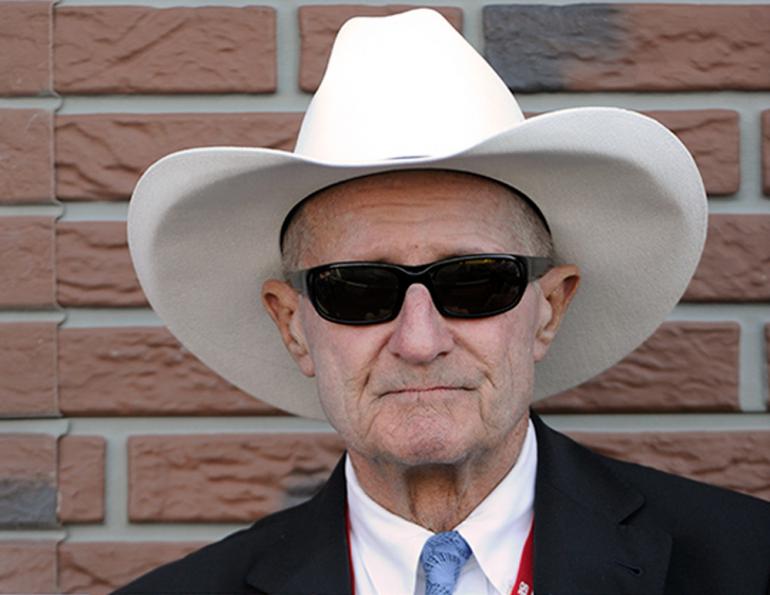

George Morris at a clinic in British Columbia in 2008, riding a student’s horse. Photo: Robin Duncan Photography

The U.S. Center for SafeSport is recognized by the United States Congress, the United States Olympic Committee (USOC), and the National Governing Bodies (NGBs) as the official safe sport organization for all Olympic, Paralympic, Pan American, and Para Pan American sports in the United States.

Many questions came up among those who supported Morris. The bombshell ban immediately prompted an “I Stand With George” Facebook page and hashtag. Why now, they ask of an alleged misconduct that apparently occurred some 50 years ago? Who came forward? What happened?

But, as George Morris’ appeal goes through the process, it’s important to understand some of the legal perspectives when it comes to sexual abuse and misconduct allegations. It should also be remembered that all investigations, whether of those in a local club or people of Morris’ stature and calibre, would be expected to be done with the utmost care and thoroughness.

The Center for SafeSport was formed in 2017 as an independent not-for-profit organization for not only international and elite sports in the United States, but also for all local clubs, national teams, and all those in between. It responds to all allegations of abuse in sport, standing behind some 14 million athletes, coaches, trainers, and other sports enthusiasts.

“Our team of subject matter experts develops best practices, policies and trainings, and regularly consults with researchers and leading organizations, such as the Centers for Disease Control, the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children and the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network,” states correspondence from the Center. “Investigators have a wealth of experience and include former prosecutors [with] FBI, NCIS, child protection services, Title IX [a U.S. federal civil rights law], and other fields, making them uniquely qualified to conduct thorough and effective investigations. Many of the Center staff have also competed and coached and care deeply about the integrity of sports and the well-being of its participants.”

For decades, major sports, entertainment, religious, and other institutions have had a responsibility to keep people safe from harm. But abuses in some form and at some level have always persisted. Because of fear, stigma, and a social attitude to either ignore or disbelieve a complainer, many abused people have been discouraged from ever coming forward to report abuse. As a result, their silence allows the abusive and often bullying behaviour to continue unchecked. Injustices that include mental/emotional and sometimes physical harm get buried for decades.

“That’s why, in part, the SafeSport Code does not put a statute of limitations on reporting abuse,” states the Center. “Anyone who comes forward to report abuse should be heard, regardless of when it happened.”

The SafeSport process is an administrative and civil law process. It is not governed by criminal law.

“Administrative law is a unique area of civil law,” says Berry Hykin, lawyer with Woodward & Co., which has offices in Victoria, BC, and Whitehorse, Yukon. “An administrative body like SafeSport has quite a lot of discretion and latitude to make their own rules and as long as they follow their own rules and abide by principles of procedural fairness then generally those decisions are not going to be reviewable. [But] that doesn’t mean they cannot be reviewed and there are lots of cases in the U.S. and Canada where administrative decisions have been reviewed by a court and have been overturned. But there’s a process for that.”

Hykin, who is a rider and an EC certified competition coach specialist, says that it seems like a lot of people are upset about the SafeSport rules because the idea that there is no statute of limitations applying to a sexual assault or a sexual misconduct is a new concept in the U.S.

“There are some states in the U.S. that have taken away the limitation period for sexual assault cases or have greatly extended it, but in most places in the U.S., as I understand it, there continue to be limitation periods for sexual assaults in both the criminal and civil context. Conversely, in Canada, there is no statute of limitation for sexual assault or sexual misconduct whether under criminal or civil law, so the SafeSport rules don’t constitute a change from the Canadian perspective.”

She says that the line between the U.S. system and the Canadian system gets blurred, both in media and in actuality. Riders might compete at shows in Canada and the U.S. and many Canadians are members of the U.S. Equestrian Federation for the purpose of competing in that country. “There’s a lot of overlap. I can understand why people are confused. It’s important for Canadians to understand that Athletics Canada has safe sport rules that are very similar to those of the U.S. Center for SafeSport. Both the SafeSport and Athletics Canada rules and processes are very similar to workplace bullying and harassment policies and complaint processes are very similar.

“If you were an employer and you had an employee who was, say, a teacher and they were accused of sexual misconduct with a minor, the very first thing you would likely do to protect yourself from liability as an employer is suspend that employee while the investigation takes place. That’s pretty much everywhere in Canada and I imagine in the U.S., though it might vary from state to state. In Canada, employers can be vicariously liable for the conduct of their employees in these cases, so employers act quickly to prevent further harm. This is somewhat analogous to SafeSport’s interim or temporary measures.”

Photo: iStock/ChrisVanLennep

The Center states that, at any time throughout the process, it may issue temporary sanctions out of an abundance of caution. Temporary measures are common tools in other institutions, similar to administrative leave for teachers, police officers, and other professionals facing charges of misconduct. But it is important to note that temporary measures do not represent a finding of misconduct, and that measures can always be appealed through independent arbitration.

Much has been made on social media that complainants can report to SafeSport anonymously. But that is not a new concept for reporting in respect of child abuse whether in Canada or the U.S.

“Everywhere in Canada and the U.S. the reporting mechanism is, if you suspect child abuse, child neglect, any kind of misconduct with a child, you can report to child welfare offices and agencies anonymously,” says Hykin. “In many cases, you are legally obliged to report depending on your relationship with the child.”

The Center states that, upon receiving an allegation of abuse, it reaches out to the accused individuals and gives them the details of the process so that they know and understand the process. They can also choose to provide witnesses, retain a lawyer for advice, and appeal any decision the Center comes to.

The Center states that people who are accused of abuse are also provided information regarding the specific allegations and, if possible, the identity of the reporter. Throughout the process, investigators interview both parties, witnesses, and review relevant evidence such as photos and text messages well before issuing any decisions.

In addition, says Hykin, if SafeSport receives a report that constitutes sexual misconduct or child abuse, there are reporting obligations in their Code that require the person making the report (unless it is the victim) and SafeSport to report to law enforcement. She does caution, though, that reporting mechanisms and how local law enforcement might address such complaints may vary from state to state and it can get more complex.

As for the age of consent, it is not as simple as whether a person was old enough to consent to the conduct. The law imposes other limitations on consent.

“In a relationship where there is an imbalance of power in which one person is in a position of authority and trust to another, they may have a fiduciary relationship,” says Hykin. “Where a fiduciary relationship exists, it obligates the person who is in the position of power and authority to exercise their fiduciary duty in good faith. Any coach is in a position of authority and trust to their students. The extent to which a student of that coach can consent to sexual activity with that coach is really limited and the younger or more vulnerable the student is in relation to that coach, the greater the imbalance of power such that any consent can be entirely vitiated. Where the coach and student are both adults, that imbalance of power starts to get mitigated and a court might start to look at other factors to assess whether consent was voluntary and freely given.”

SafeSport’s policies clearly define abuse and outline how the Center investigates allegations. It also provides guidance on how the accused can participate in the process in their own defense.

It’s important to keep in mind that the Center is not a government entity, has no legal authority, and imposes no legal penalties. While its policies and processes are transparent, safeguarding the identities of those who come forward and disclose is critical. As a result, the Center does not comment on individual matters. To ensure people continue to report abuse, they need to be able to do so free from fear of retaliation and harassment.

Since SafeSport is a private, not-for-profit entity and not a government actor, constitutional rights likely do not come into play. Hykin says that a government’s constitution sets out the rights that individuals have in relation to the exercise of power by government, not by private entities. But individuals have a right to procedural fairness.

“This is a voluntary organization and participating in Olympic sports is a privilege, not a right,” she says. “It might not feel that way when you have to join the organization to participate in your sport of choice, or to make your living from that sport, but the fact remains that membership isn’t something imposed by the state. But the sanctions are real, and they do have significant repercussions for the people who are subject to them. A lot of the blowback [in the George Morris case] seems to be people’s concern about the disproportionality of the sanctions in relation to an historical complaint. But if the allegation was that he had raped a little boy yesterday, I think people would have less hesitation about this kind of sanction being imposed on him. But the fact that it’s about an historical claim, the details of which are largely confidential, somehow people think the sanctions should be less severe or even less likely to be imposed.”

False reporting, while uncommon, is taken very seriously.

The Center is often asked about false reporting, but research indicates it is rare. It is reported in the National Sexual Violence Research Center that false reports of sexual assault account for two to ten percent. Still, the Center takes concerns about false reports seriously and has safeguards in place to prevent the system from being misused. In addition to conducting a thorough investigation, the SafeSport Code prohibits false reporting, which the Center enforces.

Hykin says that, on social media, a lot is being made of false allegations and the risks they pose to people’s reputations and livelihoods. But, as the Center states, the number of false allegations is really low and her understanding that it is indeed in the two to ten percent range.

“That number doesn’t take into account that probably 80 percent of sexual misconduct cases aren’t reported, so the number of false allegations is in reality even smaller than that,” says Hykin. “The concern over false allegations is really disproportionate when you think how many sexual assaults are occurring and not getting reported, investigated, or sanctioned. The SafeSport Code has a whole bunch of protections built into it to address the risk of people filing false allegations. There are sanctions for knowingly filing a false allegation, quite severe, and they have made a distinction between a false allegation and an unsubstantiated allegation with different sanctions in relation to each.”

In today’s sports climate and the obsession of many young athletes to reach their Olympic goals, they often will remain silent in the face of sexual abuse. This is not unique to equestrian sports but spans the sports spectrum. In fact, in Marquette Sports Law Review, writer Daniel Fiorenza states in his article Blacklisted: SafeSport’s Disciplinary Policy Restrains a Coach’s Livelihood, that the U.S. Olympic Committee estimates that one in four girls and one in six boys will be sexually abused before the age of 18.

And it’s not just the U.S. where such outrages take place. In February 2019, a CBC investigation into sexual offenses in sports in Canada revealed that at least 222 coaches involved in 36 different amateur sports across the board over the last 20 years had been convicted of various offenses against some 600 victims under the age of 18. Of these, equestrian sports accounted for seven charges and five convictions.

Getting up to speed with the potential for victims to come forward in future years, Equestrian Canada (EC) announced in July this year that they have retained the services of Brian Ward from W&W Dispute Resolution Services Inc. to provide the equestrian community with expertise to properly address complaints. It’s EC’s step forward for its own Safe Sport movement. Ward has a long history of working in dispute resolution within the sport system. He will be receiving complaints, determining if they are admissible, then dealing with each case with full confidentially.

For Morris, even though he is pursuing an appeal, he must deal with the most severe sanctions placed on him by the Center for SafeSport based on the investigator’s findings of fact. Currently, he now no longer has any ability to participate in the sport at any level. In addition, those sanctions could impact anyone who aids Morris in contravening them.

“That’s a big hit,” says Hykin. “I can understand why people are so upset to see such an iconic figure removed from the sport, especially if they think they may be impacted in some way by their association with him in whatever context. People are also upset that the sanctions were imposed and announced before the arbitration has taken place. I don’t see how it is much different than announcing the outcome of a trial in BC Supreme Court while the matter is being appealed to the BC Court of Appeal. The purpose of the sanctions is to protect people. They should take effect immediately in order to do that, otherwise we are leaving potential abusers in a position to continue abusing people while we investigate. What we haven’t sorted out as a society is how to restore someone’s reputation, livelihood, and life after the fact if they do successfully appeal a decision through arbitration. Interestingly, at the allegation and investigation stage of the process, we collectively seem to be very quick to blame victims and side with the accused, and yet after someone has a successful appeal and been exonerated, we seem collectively equally unlikely to believe or support that person. That’s where some of the fear about false allegations comes from. I don’t know how to fix that. I wish I did.”

Hykin would be the first to recognize that no administrative process is perfect and there have been many criticisms of SafeSport. While the road to SafeSport’s creation was paved with good intentions, lack of funding, high profile and seemingly heavy-handed sanctions, lack of transparency, and case overloads for investigators have critics seeing the organization coming up short. Perilously so.

While the #MeToo movement had many across society coming forward with dark secrets of past abuses, in rare cases some of those accused chose to pay an ultimate price. In February 2019, popular U.S. show jumper Robert Gage received a lifetime ban from the USEF after sanctions imposed by SafeSport due to sexual misconduct involving a minor. He appealed but committed suicide days before his appeal was to be heard. But we should acknowledge that we do not know the full extent of Gage’s torment that led to suicide, and it may not only have been the lifetime ban.

While the Center largely focuses on investigating allegations of abuse, prevention education is core to its mission. Since opening its doors, it has trained more than 800,000 people to recognize red flags, understand appropriate boundaries, and report abuse to the Center. This comprehensive training is available online and in-person, and engages athletes, coaches, and others to understand their responsibility to report abuse and misconduct. Additionally, through its investigative process, the Center has resolved more than 1,700 cases, found violations in 551 cases and rendered 285 people permanently ineligible to participate in sports under the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee and the National Governing Bodies’ umbrellas.

“If what comes out of this public debate are improvements in the process, that’s real progress,” says Hykin. “Legislators are always amending laws and administrators are always amending their codes. SafeSport has the authority to write their own rules and they can certainly make changes and adapt to correct issues as they come up. But that doesn’t mean that all the criticisms of SafeSport are valid or should be cause for amendments. We have to stay focused on the purpose of the SafeSport organization as a whole, which is to protect people from harm.”

Main photo: Robin Duncan Photography