By Jess Hallas-Kilcoyne

It began when Normand Latourelle, one of the founders of Cirque du Soleil, decided to incorporate a horse into Légendes Fantastiques, the show he’d created based in Drummondville, Quebec. But he quickly realized that the horse was stealing focus from the performers.

“Every time the horse was on stage the audience was not looking at the performers, they were looking at the horse,” recalls Latourelle. He laughs. “I thought, ‘that’s interesting.’ We put so much effort into doing nice costumes and fabulous make-up and choreography, and nobody cares. They’re looking at the horse.”

Attracted to the idea that horses could be great performers, Latourelle purchased six horses and, with the help of some friends who were acrobats and a movie stunt rider, began exploring the possibility of a show featuring several horses. From there, the idea grew until, a decade or so later, Cavalia was born in 2003.

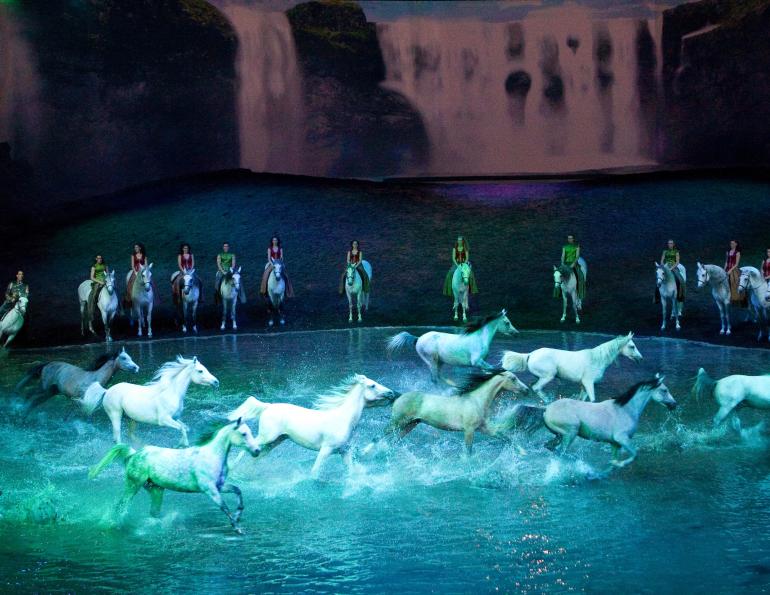

In Cavalia, often referred to as “Cirque du Soleil with horses,” up to 50 horses and their riders or handlers share the 50 metre wide stage with acrobats, dancers, aerialists, and musicians, all performing in front of a 70 metre wide screen that provides a backdrop for projections. The combination of equestrian and performing arts with multimedia and special effects created a production unlike anything seen before. The world was dazzled by Cavalia, but Latourelle wasn’t finished yet.

“Throughout the creation process and throughout the presentation touring process I had the idea of doing a second show,” he says. And so a second production, Odysseo, was launched in 2011. While Odysseo shares certain elements with the original Cavalia – music, mixed media, acrobatics, and, of course, horses – Latourelle describes the two shows as being quite distinct.

“It’s like listening to a piece of music composed by Mozart, or listening to a piece of music by Beethoven. Both of them are music – they’re using the same instruments, the same type of orchestration – but each brings you to another world.”

Cavalia founder and artistic director Normand Latourelle is enthusiastic about letting each horse’s personality and individuality shine through in their performance. Photo: JF Leblanc

Latourelle goes on to explain that Cavalia is about humankind’s discovery of the horse, and the evolution of the relationship that grew between horse and human. Odysseo, on the other hand, is, as the name implies, about the journey that horse and human have taken through history, travelling together side-by-side across different landscapes and cultures.

Apart from theme, there are several logistical distinctions between the two productions. “Odysseo is much bigger,” says Latourelle. “It’s much more extravagant.”

Odysseo’s 67 horses and 45 riders, acrobats, and musicians perform under the production’s ten storey high White Big Top – the largest in the world – and in front of a video backdrop equal in size to three IMAX screens.

“Everything is big here,” says Latourelle. “The stage is the equivalent of three ice hockey arenas. The tent is bigger than a football field.”

The desire to push the envelope is also reflected in Odysseo’s equestrian numbers.

“We push the limits of having free horses on stage much further than anybody has ever done,” says Latourelle. “At one point you have almost 40 horses on stage totally free, and half of them can be stallions. You will not witness this anywhere else in the world. We have pushed the relationship between humankind and horses.”

With 40 horses on stage, there is a certain element of unpredictability to each performance of Odysseo.

In the Carousel number, 16 big, grey horses and their riders, garbed in flowing costumes, perform a series of intricate patterns. Photo courtesy of Cavalia

“Every show varies from one show to the next because we don’t control the horse” says Latourelle. “We’re following the horse. It’s a different approach. Sometimes the horses do what they want and this is what I like – the horse that is just being a horse. You see happy horses on stage and that’s the main thing.”

Chantal Pearson, rider, trainer, and performer for Cavalia and Odysseo, confirms that sometimes elements of the show don’t go strictly as rehearsed, but agrees with Latourelle’s view that this is a strength rather than a flaw. “It mostly happens in the liberty numbers,” she says. “Some nights the horses just decide not to follow us. They are horses. Sometimes they don’t want to do it and we have to live with it. It’s not so obvious to the audience sometimes, but even when it is they still love it.”

Pearson assists with the training of nine Arabians for a liberty number in Odysseo, and performs with them on stage once or twice a week. “I really love liberty because you can’t cheat,” she says. “If the horses don’t want to do it one night, well they won’t. It happens, but we’re just going to try to ask them a different way.”

Never does “a different way” include harsh training methods. Latourelle is insistent upon that. “Everything is done in harmony with what the horses are,” he says. “I accept that when you’ve got 16 horses all doing the same thing on stage they don’t all have their heads at the same height. This is okay for me. It’s even better, because they show their own personality, they show their own physicality. It doesn’t mean they’re not great performers.”

It can take anywhere from a few months to several years to turn a horse into a great performer.

The horses in Cavalia and Odysseo have to be desensitized to a variety of objects, situations, and sensations, such as flag streamers, acrobats and aerialists working around them, and trick riders hanging from their bodies. Photo: François Bergeron

“It depends on the discipline they’re doing,” says Pearson. “It takes about two months to train a horse for vaulting… but for the high school [dressage] – to teach a horse how to do piaffe and half-pass or flying changes – this is way longer. It can take years to teach a horse to do these things very well.”

Training programs are also adjusted according to the individual.

“Training varies from one horse to another,” says Latourelle. “They don’t learn at the same speed and we respect that. If they don’t learn quickly, we go slower with them.”

“All the horses in the show are still improving,” adds Pearson. “In every city we teach them new things. For example, a horse may start in the show doing Carousel, and then once he’s ready he will do high school.”

One of the most interesting things about Odysseo’s stable is that every horse is expected to be able to eventually perform a minimum of three different disciplines for the show.

“In the horse world, a dressage horse does only dressage, a jumping horse does only jumping,” says Latourelle. “Here in Odysseo, our horses jump, do dressage, and do liberty. Or they do trick riding, roman riding, and liberty.”

“It really keeps them interested in the work,” says Pearson, “My horses don’t do the same gymnastic or the same trotting work every day. For example, they’ll do jumping, then the day after I’ll do liberty, then roman riding, then dressage. That way they are not always doing the same routine and they don’t get bored.”

When the horses are on tour, they can expect to be ridden two to three times daily – a schooling session in the morning, a rehearsal (if one is scheduled) in the afternoon, and the performance in the evening (if the horse is scheduled to perform that night). The riders and trainers are extremely careful never to overwork the horses, and each horse’s personalized training program is custom tailored to the individual’s temperament and capability.

“All the riders have to know their horses,” says Pearson, referring to the three horses she works with personally (apart from the nine Arabians). “I know these horses so well that I know what they’ll need to do the show that night. For example, one of my horses was a little tired yesterday. This morning I only did walk with him and I was stretching him and making him feel good. Then this afternoon in the rehearsal he was very good. I know he will be good in the show tonight. My other horse is doing trick riding in the show and is a little full of energy. So this morning we did a little more with him.”

In addition to carefully regulating their work schedules on tour, Latourelle ensures an adequate number of back-up horses so that company horses can rotate back to home base – a farm in Sutton, Quebec – for vacation time. “They have pasture, they eat grass for six months, and they come back happy to be back,” says Latourelle.

It can take up to four or five years to train a horse to perform the high school dressage routines in Cavalia and Odysseo. Photo courtesy of Cavalia

But not all horses are cut out to perform in Cavalia or Odysseo. When it comes to sourcing equine performers, selection is based on the principle, “form follows function.”

“The horses that are doing vaulting and trick riding, they have to be strong and really fast,” says Pearson. “So we’re looking more for Quarter Horses, Mustangs, and Appaloosas. For the dressage, we’re more looking at the Lusitanos and Spanish Purebreds. If a horse is going to do high school [dressage], we need to find a horse that moves very well. For liberty, of course, we can use all the horses, though the Arabians are very, very good in liberty, in my opinion. They’re so full of energy that you’ve got a lot to work with. They’re always playing.”

Speaking with Pearson, her genuine love for the horses in her charge shines through. Touring with Cavalia and Odysseo might feel like a world apart, but underneath the beautiful costumes, dramatic make-up, and intricate choreography are riders who, like all other horse people, simply love their horses.

“There’s not a day that passes when I didn’t learn something from my horses,” says Pearson. “I really love the fact that I come every morning and have my horses there and I get to work with them and really create something with them. It’s really about building something. The work we did yesterday is going to influence the work we do today and tomorrow.”

“I can trust [my horses],” Pearson continues. “In the show, I can look at my Arabians or my Carousel horse and know that they’re going to do it with me. That’s a really, really good feeling to know that your horses are there with you and they’re happy to do it because they know it makes you happy. That’s amazing.”

It’s clear that the close off-stage relationship between the horses and their riders and handlers is part of what makes the on-stage performances of Cavalia and Odysseo so captivating for audiences around the world. There is evidently something in the bond between humans and horses that is relatable for people around the world, regardless of nationality, language, or culture.

Latourelle sums the universality of horses up best when he describes the research he did prior to founding Cavalia. “I started to read books to learn about the horse and I found that the history of the horse was the history of humanity… horses are part of who we are as humankind.”

For further information about Cavalia and Odysseo, please visit www.cavalia.net.

Main article photo: François Bergeron

This article originally appeared in the April 2013 issue of Canadian Horse Journal - Central & Atlantic Edition.