By Dr. Crystal Lee, DVM, DACVS

Lameness is an indication of a structural or functional disorder, in one or more limbs or the spine, evident while the horse is standing or in movement. It can range from very mild discomfort, which may only be perceived by the owner or trainer as a decrease in level of performance, to severe pain in which the horse is unwilling to bear weight on the limb. As one of the most common and most expensive medical problems in horses, lameness represents a large concern to the equine industry as well as to individual horse owners.

When your horse presents to the veterinarian for lameness, we will often start with a thorough palpation of all four limbs and the spine, checking for heat, swelling, or pain on palpation. We will also check for increased fluid in each of the joints and tendon sheaths, which is referred to as effusion. A hoof tester exam is often done as well, checking for pain as pressure is applied to different regions of the sole.

Visual Examination

A visual exam is the next step of the lameness evaluation. The vast majority of lamenesses are easiest to perceive at the trot. The horse will often be evaluated while being trotted in hand on hard ground as well as in a circle, whether in hand or on the lunge line. Many lamenesses will manifest more strongly when evaluated in a circle. It is often helpful to watch the horse both on hard and soft ground, as the lameness may appear differently in these situations. Some horses with subtle lamenesses will also be evaluated at the canter, or while being ridden.

Upper limb flexion of the right forelimb is performed here for 30 seconds before trotting the horse to evaluate for an increase in lameness. Photo: Kirby Penttila, DVM.

The nature of the visual exam is very subjective. In subtle lamenesses, it may be very difficult to tell which limb is the source of the pain, especially if multiple limbs are involved. Different veterinarians will focus on different aspects of the horse when watching a horse being trotted for lameness examination, but there are some commonalities. It is often helpful to look up at the motion of the torso and head of the horse rather than being distracted by the movement of the limbs themselves.

The majority of forelimb lamenesses are “impact” lamenesses, which means that the discomfort is occurring as the limb strikes the ground. A horse with impact lameness will not drop its head as low when this limb is on the ground as it does when the other limb is on the ground. Other forelimb lamenesses are “push-off” lamenesses, which means that the discomfort arises as the limb is pushing off the ground. A horse with push-off lameness will throw its head up as it pushes off the ground to help take the weight off the affected limb. In either case, what we perceive is the head being higher on the lame limb and lower on the sound limb (known as a “head nod”).

Subtle hindlimb lameness is often more difficult to visualize than is forelimb lameness. Many people stand behind the horse and watch the hips move on either side of the pelvis. On the side that is the source of the lameness, there will be more up and down movement of the hip. Other people watch the entire pelvis as a whole. In this case, the pelvis sinks less as the lame limb strikes the ground with an impact lameness, and rises less with a push-off lameness. Determining whether the left or right hind limb is affected is often the most difficult question to answer in the evaluation of a subtle lameness.

Another strategy that is useful in many cases is to perform flexion tests. Either the lower limb or the upper limb is held in flexion for a period of time (usually between 30 and 90 seconds), and then the horse is trotted off in a straight line. If the lameness is exacerbated by the flexion, it is an indication that the source of the lameness is in the region that was flexed. If the limb that is the source of the lameness was easily determined by the visual exam, flexion tests can be performed on this limb to isolate the region of the limb that is the source of pain. If the primary limb is still in question after the visual exam, all four limbs can be flexed to try to exacerbate the lameness enough to make a diagnosis.

An ultrasound exam of the pastern area is performed. Photo: Kirby Penttila, DVM.

Once the primary limb which is the source of lameness has been identified, the next step is usually to perform nerve blocks. This procedure involves injecting a small volume of local anesthetic (freezing) under the skin directly over the nerve that allows the horse to feel certain parts of its limb. This local anesthetic takes away the sensation to the portion of the limb below the injection. The horse is trotted away after the nerve block has taken effect. If the source of the lameness is in the region below the injection, we would expect the lameness to be improved. If this is the case, we have successfully narrowed down the options to isolate the region that is the source of the lameness. In general, we will start with nerve blocks in the lower limb, and work our way up the limb.

In certain cases, local anesthesia can also be injected directly into the joint in question to allow a more specific joint block. This technique carries a very small risk of introducing infection, so nerve blocks are often utilized first. However, joint blocks do not diffuse up the limb as nerve blocks do, so it is possible to isolate a more specific region of pain. Depending on the type of local anesthesia used, the lack of sensation in the area blocked lasts several hours.

It is important to note that the horse must be consistently lame in order to perform nerve or joint blocks, so that the examiner is able to tell whether the block has resulted in significant improvement. However, if this is the case, nerve blocks are a valuable phase of the examination. The results of a nerve block allow the examiner to image a specific area and know definitively that any changes seen on radiographs or ultrasound are truly the cause of the horse’s current lameness. Otherwise, it is possible that a lesion identified on radiographs was preexisting and is not actually causing the horse a problem at this time.

Wireless Inertial Sensor-based Evaluation

Although traditional lameness evaluation relies on individual subjective examination, there are several methods of objective examination available. Most of these methods, such as force plate evaluation and camera-based kinematic evaluation on a treadmill, are usually only relevant in a research laboratory setting. Here at Burwash Equine Services in Calgary, Alberta, we have recently started incorporating wireless inertial sensor-based evaluation into our standard lameness examinations, using the Equinosis Lameness Locator system. To my knowledge, there are only eight of these systems in use in Canada at this time.

A wireless inertial sensor is placed on the horse’s head, attached to a head bumper. Photo: Kirby Penttila, DVM.

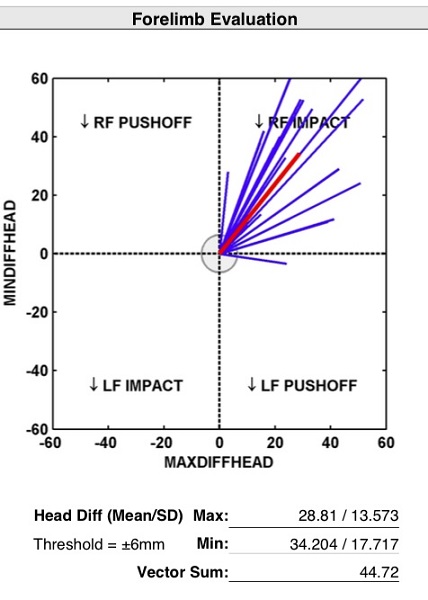

The Equinosis Lameness Locator system utilizes three wireless inertial sensors that are placed on the horse at the beginning of the exam: one on the horse’s head, another on the centre of the pelvis, and a third on the right front pastern. Instrumentation of the horse is quick, easy, and noninvasive. The sensors send data to a tablet computer for immediate analysis, and supply a one page report that summarizes the difference in head and pelvic movements which correspond to lameness in a certain limb.

A horse is instrumented with wireless inertial sensors (the Equinosis Lameness Locator) to perform an objective lameness evaluation. Photo: Kirby Penttila, DVM.

There are many reasons why objective lameness evaluation is advantageous for both horses and horse owners. The sensors are able to sample up to 20 times faster than the human eye, and allows the system to pick up on subtle assymmetries that would otherwise be missed. Multiple limb lamenesses or assymmetric movements in other limbs that are compensatory for the primary lameness can also complicate what the veterinarian sees, and are more easily distinguished with objective evaluation. The final analysis correlates well to subjective exams, and has been proven to identify lameness of a lesser severity when compared to the consensus of subjective evaluation by experienced veterinarians.

Because the data from the wireless inertial sensor-based system puts an actual number to the lameness in each individual limb, it is possible to quantify the improvement seen after a nerve block or a flexion test is performed. It is also useful to be able to assess improvement at recheck examinations and during a rehabilitation program by comparing the numbers to those obtained at the initial examination.

The vertical acceleration measured by the wireless inertial sensors is used to generate a report detailing the asymmetries in head position between the left and right halves of the stride.

The end goal of all of the above procedures is to determine which limb is primarily affected, and further, which region in that limb is the source of the pain. It is a bit amazing if you stop to think how much time and money would be saved if the horse could just tell us what hurts! However, once we have isolated a region that is the source of pain, a diagnosis can often be reached using imaging techniques such as radiographs and ultrasound. If the findings from these are equivocal, it may be necessary to use more advanced imaging techniques such as MRI, CT, or bone scan. A definitive diagnosis that is reached with a thorough lameness evaluation and diagnostic imaging allows precise treatment that is specific and directed at the disease process, and will give your horse the best possible chance of success.

Main photo: ©CanStockPhoto/Edu1971